Tabby Booth Believes Confusion in Art Can Be Productive

👁 119 Views

Some artists know what they want to make early on. Others take time to figure it out. For Tabby Booth, it developed slowly over time. Her work grew from instinct, environment, and observation, and has become grounded in folk stories and hands-on processes. For this week’s Best of the Art World series, we’re honoured to trace that journey, shaped less by structure and more by place, experience, and a deep sensitivity to stories, textures, and atmosphere.

Tabby grew up in a creative household. Making things was part of daily life long before she thought about being an artist. People around her drew, painted, wrote, and moved as part of how they spent time together. Her parents weren’t working artists, but art was present in ordinary ways, in the objects around the house, in colours and materials, and in how ideas were talked about and taken seriously.

Because of this, Tabby became interested in people, stories, and places that feel used and real rather than polished or staged.

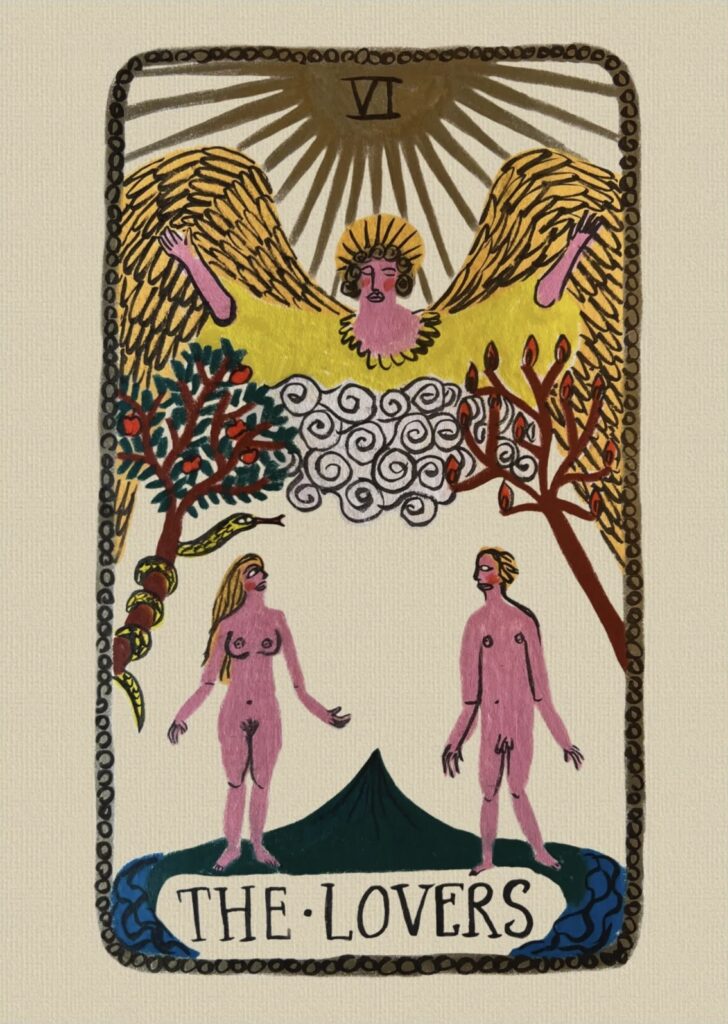

As she moved into formal study at Central Saint Martins and later into adulthood, Tabby’s sensitivity to her surroundings only deepened. From living on a London houseboat to eventually settling in Cornwall, each place affected how she felt day to day and how she worked. Tabby describes herself as a very visual person. Her mood, energy, and focus change depending on her surroundings. This shows up in her work, which often includes folk references, symbolic figures, and imagery that feels old and current at the same time.

The figures and creatures in Tabby’s work don’t belong to one clear time or story. They aren’t meant to explain themselves. She doesn’t usually plan a piece before starting it. Instead, she works through shape, surface, and arrangement until the image begins to settle. Meaning isn’t added deliberately. It comes through the process of working.

People often respond to her images in personal ways, and she’s comfortable with that. She leaves space for viewers to bring their own memories and feelings to what they see, rather than guiding them toward one interpretation.

Alongside her own work, Tabby has also created space for other artists. She co-founded Cygnets Art School and Sailors Jail Gallery with her husband. She didn’t set out to become a curator, but it happened naturally. She enjoys bringing different artists together and supporting people who may struggle with the practical or organisational side of the art world. For Tabby, community is built through showing up, helping out, and working alongside others.

The way she chooses materials comes from the same place. She often works on wood panels and uses old frames and worn surfaces. Scratches, marks, and uneven textures are left visible. The process is hands-on and sometimes unpredictable, and she allows mistakes to stay. Illustration is also an important part of her work, giving her a different pace and flexibility. Moving between physical materials and digital tools continues to shape how she works today.

Let’s get to know Tabby Booth through her own words, as she reflects on intuition, material, community, and the freedom that comes from trusting your own visual language.

Q1. Can you share how your early environments and childhood influences shaped your creative background and led you toward the folk-inspired, symbolic style you work in today?

I was very lucky to grow up in a deeply creative household. Neither of my parents worked professionally as artists, but they absolutely are artists – they can both draw and paint amazingly. My dad is a writer, and my brother a choreographer, so creativity was always part of the atmosphere. Our family home was full of colour, texture, books and interesting objects, so that shaped my love of art and interiors from a young age. As I’ve grown older, I’ve realised how entirely visual I am as a person. My immediate surroundings have the biggest impact on my mood and how I feel creatively. I’m drawn to things with character, history and a raw unpretentiousness – which is what folk art does so well.

Q2. Your silhouettes and beasts seem to exist outside of time, almost like remnants of an imagined civilisation. When you create, do you see yourself as interpreting old stories, inventing new ones, or tapping into something more instinctive and subconscious?

For me, it’s definitely subconscious – I rarely plan my work and create as instinctively as possible: exploring form, texture and composition, until something clicks and it just feels right. If I start to think too much about something, or question it, that’s where it tends to go wrong. I don’t create with a deliberate meaning or references in mind, but of course people will find their own meaning within my work. Someone said recently that it makes them feel as though they’re looking at their shadow self, their primitive nature, and I love that. It’s not about obvious meanings, but creating something that resonates on a deeper level, even if you can’t quite put your finger on what it is.

Q3. You co-founded the art school Cygnets Art School and the gallery Sailors Jail Gallery with your husband. How has the dual role of being both an artist and a curator/mentor influenced your creative voice and how you view your own work?

Being a curator had never been on my radar, but opening Sailors Jail Gallery in 2023 happened quite serendipitously. Once the idea came up, it just made perfect sense because I’m such a natural curator – I love collecting, contrasting, and putting things together, and I’m obsessed with discovering new artists and their work. I know that many artists are incredibly talented but often struggle with the organisational, administrative, and business side of things. With Sailors Jail, we have the chance to support these artists and help get their work out into the world.

There’s something incredibly inspiring about being part of a creative community, where everyone is on the same journey, but equally has their own unique voice within it

Q4. How do you view the relationship between folk art traditions and contemporary illustration especially in your own work? Do you feel you’re bridging a gap, subverting tradition, or re-inventing it?

These days, it feels almost impossible to create something completely unique. We’re all inspired by everything we see, and with so much available online now, influences are everywhere in a way they weren’t historically. Folk art appeals to me because of its timeless, instinctive qualities and its simple, symbolic storytelling. In my work, I’m not consciously trying to reinvent it, but I interpret those traditions through my own instincts and ideas, so my work sits somewhere between homage and contemporary reinterpretation.

Q5. You mention doing daily prompts (#thepromptpot) and embracing intuitive drawing rather than over-planning. Could you walk us through how spontaneous intuition plays a role in a piece you perhaps didn’t expect to turn out the way it did?

Doing illustration challenges on Instagram has absolutely transformed my practice. I think having some kind of structure or restriction – even something as simple as a single word – is incredibly powerful. For me, too much freedom can lead to overthinking; having a starting point helps focus ideas, refine my style, and explore themes I might not have considered otherwise. Often, the prompts that initially feel the most daunting or outside my comfort zone turn out to be my best pieces, because they push me to try something different. And interestingly, the images I’ve been least confident about often resonate most with other people when I share them online. It’s taught me to trust intuition and embrace the unexpected in my work.

Q6. Working on wood panels, scratching surfaces, and using waxed finishes gives your pieces a tactile, weathered presence almost like relics. How does your physical process of carving, scraping, or layering shape your relationship with the image itself?

When we first opened Sailors Jail, I knew I needed to create some artwork for the gallery. Although I’d studied illustration a decade before that, I knew now that I wanted to do something tactile and textured. I had a longing to work with my hands, and create physical pieces – tying into my love of interiors. I work a lot with wood and old frames, using techniques like sgraffito, where I layer paint and then scratch away at it. I love this process because it’s unpredictable – sometimes the tool slips or marks appear that aren’t entirely deliberate – and those imperfections are the best bits. I have ended up coming back to the illustration now as well, and am really grateful for that duality in my practice: I love being able to draw digitally anywhere, but also the physicality of going to my studio to paint.

Q7. Animals and mythical beasts recur in your pieces, but they never feel merely decorative. What emotional or psychological qualities do these creatures allow you to express that a human figure might not?

I think animals are inherently full of character, which is why I always return to them as the main theme in my work. I love that viewers can find their own meanings in a creature – perhaps it reminds them of a pet, or a character from a fairy tale they loved as a child. Adding the eye is always my favourite part of any piece, because that’s when the character truly reveals itself.

Q8. Your art often lives in the home: framed, on walls, part of interiors. What do you hope a viewer feels when they bring one of your pieces into their space and does that differ from being in a gallery context?

I create my work entirely with the home in mind. Gallery spaces are, of course, important for showing work, but ultimately my pieces are meant to live in someone’s personal space. They’re designed to bring depth, character, and a sense of history to a room, while also adding an element of playfulness, which I think is absolutely essential in any interior.

Q9. Cornwall is saturated with local legends, shipwreck tales, and maritime lore. How much of your storytelling emerges from Cornwall’s landscape, and how much comes from internal narratives you’ve carried for years?

Cornwall is an incredibly magical and inspiring place – it really feels like its own country, and I didn’t fully realise that until I moved here and lived immersed in the landscape and creative community. I’m so lucky that my studio looks out across the rolling hills down to the sea; it’s easy to get lost imagining what this place would have been like hundreds, even thousands, of years ago. Much of my work now feels tied to Cornwall, but some of these themes, like mermaids, have actually been constants for me for years. It feels very full circle to be living and working among them now – almost as if they were calling me here the whole time.

Q10. If you could develop a long-term project that existed outside the boundaries of commercial expectation perhaps community-based, environmental, or site-specific what form would it take and why?

I’ve always been fascinated by large-scale ancient artworks, like the chalk figures and animals on the sides of hills. I’d love to create a project on that kind of scale – something that exists in the landscape itself. There’s something magical about the idea that you catch a glimpse of it from a train journey or happen upon it while walking through the countryside, and it becomes this shared folkloric experience.

Q11. What internal questions or themes are currently driving your newest bodies of work? Are you trying to resolve something, expand something, or explore something you haven’t touched before?

It’s been a really busy year with both my paintings and illustration work, and I’m so grateful for that. But as the year draws to a close, I’m trying to carve out some time to create work just for myself, which I haven’t done in a long while. I recently did a life drawing workshop – my first in years – and I’m excited to develop those drawings into large-scale paintings, possibly on fabric. I’m also planning a social media giveaway later this month, where I’m asking people to give me illustration prompts to create new prints from. I’m really looking forward to exploring that

Q12. What advice would you give to emerging artists who feel torn between fine art, craft, illustration, or storytelling especially those who don’t yet know which “world” they belong to?

My advice would be to start by focusing on one thing. It’s hard when you’re a creative, as often you want to do everything all at once! But at the beginning, it’s important to give people a clear sense of what you do. What does your work represent? What’s your visual narrative, and how can people engage with it? Once you’ve established that, then you can start to expand and apply that to other areas.’

As we come to the end of our conversation with Tabby Booth, what stays with us most is how deeply she trusts her instincts. Her work doesn’t begin with fixed ideas or planned meanings. Instead, it grows through attention to materials, to mood, and to what feels right in the moment. She allows the work to develop naturally, without overthinking or forcing it, leaving space for meaning to appear in its own time.

What Tabby builds over time is a practice shaped by sensitivity to place, to process, and to the stories that quietly stay with us. Folk traditions, animals, and imagined worlds return again and again in her work, not as symbols that need explaining, but as familiar forms that carry feeling and memory. Her pieces often feel worn-in and timeless, even when they are deeply personal, inviting viewers to connect in their own way.

There is a generosity in how she works. She trusts the process, and she trusts the people encountering her work. Her pieces don’t ask for a single interpretation or a clear answer. Instead, they offer room to pause, to feel, and to bring personal experiences into the work. Whether seen in a gallery or living in someone’s home, her art encourages a slower, more intuitive way of looking.

That openness extends beyond her own practice. Through building creative spaces and communities, Tabby creates room for others to grow as well. Supporting fellow artists, sharing opportunities, and working together feels like a natural extension of how she approaches her own work with care, curiosity, and a belief in shared creative energy rather than competition.

Tabby Booth leaves us with a reminder that feels especially relevant today: that intuition is something to trust, that imperfections give work its character, and that art shaped by lived experience often speaks the most honestly.

Follow Tabby Booth to explore a practice guided by curiosity, material exploration, and a deep confidence in trusting your own visual language.