Inside Richelle Rich’s Ice Cream Stories and the Memories They Hold

Richelle Rich is an artist with a deep curiosity about power, nostalgia, and the hidden stories objects can hold. She believes everything is political and is particularly interested in how women are represented in history, culture, and art. Her work explores forgotten stories and how everyday objects carry emotions and memories.

In this interview, Richelle takes us through her journey—from growing up in a seaside town in England, studying at Central St. Martins and the Royal College of Art, and eventually moving to Los Angeles. She shares how different places, from the Isle of Wight to the Mojave Desert, have shaped her perspective and creativity. She talks about how her art helps her make sense of the world, why she’s drawn to themes of justice and equity, and how she finds meaning in objects that others might overlook.

She also discusses the challenges of being an artist, the pressures of success, and the importance of finding a supportive creative community. Her advice to emerging women artists is to be brave, not compromise, lift each other up, and always keep creating.

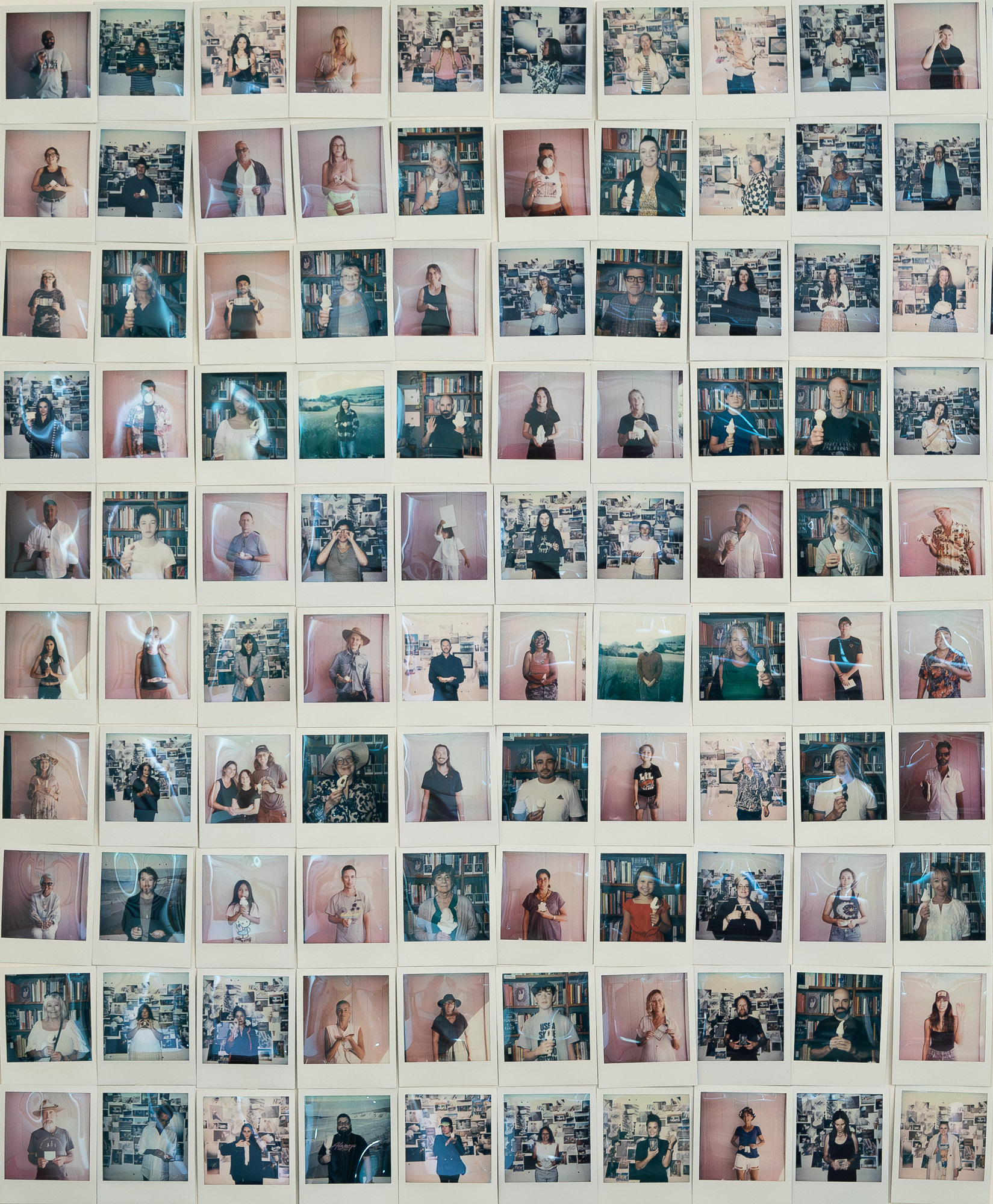

I am interested in systems of power and the politics of nostalgia. I am fascinated by lost or forgotten stories and how objects are magically contaminated by our history, emotions, and memories. I am currently obsessed with Mr Whippy, British soft-serve ice cream. I’m using it to interrogate both political and personal stories. I was born in London but spent my childhood on the Isle of Wight, a place of tourists, unpredictable seasons, and seaside nostalgia, famous for smugglers and the perfect bones of vast dinosaurs buried in huge white chalk cliffs. My grandfather owned hotels that closed in the winter and re-opened every spring, so seasonal tourism was a backdrop to my early life.

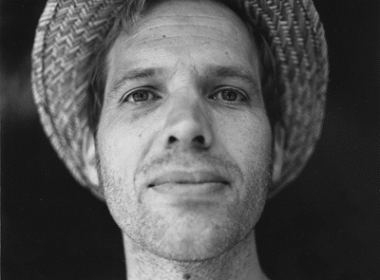

When I was 1,6 I left school and moved to London. I worked during the day doing every kind of job! Reception, shelf filling, modeling, photographers assistant, advertising production and most nights I attending art evening classes. I just wanted to study art. In 1995, I graduated from Central St. Martins School of Art Printmaking and Photo Media and went on to do my MA at The Royal College of Art. In 2013, I moved to Los Angeles with my husband, musician Harry Waters, and our two sons. We live and work in Santa Monica. In 2020, during the pandemic, I also renovated a 1950s property in the remote desert of North Joshua Tree, where I can work.

We have created a self-structured residency program and hold workshops there; it’s called The Art House Joshua Tree. I have exhibited internationally, including solos shows at Gallery 169 (Los Angeles) Hirschl Contemporary, Cork Street (London), Michael West Gallery (Isle of Wight), Standpoint Gallery (London), and group shows at NCK Gdansk (Warsaw), and Soft Core LA (Los Angeles) among many others. I am the winner of the Augustus Martin Prize and Falkiner Fine Paper Award and was shortlisted for the ACK Arts Prize. My work and my writing have been featured in Art Forum, Artnet, Art Review, The Guardian, The Financial Times, The Times (London), The Independent, Contemporary Magazine, Time Out (London), Harpers, and Queen.

1. Your work explores power and the politics of nostalgia—what draws you to these themes, and how do they shape your art?

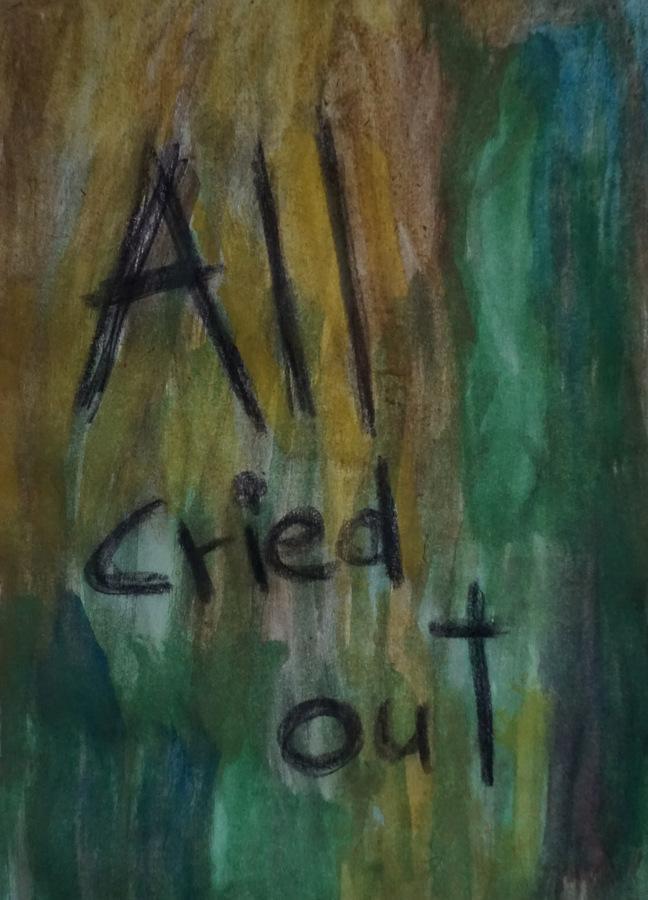

I believe that everything is political. I am particularly interested in how and where women are represented in culture, in our media, throughout history, and within art and art institutions. I am curious about how we all live. Our relationship to the truth. I love to excavate stories, deep dive into a subject, and explore it from a multitude of angles while I am making my work. That intensive exploration of perhaps the science or history of materials I’m using or a location I am shooting sits alongside my practice. As I progress, the work becomes more personal. I recently had the pleasure of attending a local book reading where Sonya Walger read from her wonderful new book ‘Lion’. She referenced the phrase ‘Gnaw your own bone’, paraphrasing Thoreau. I think that’s me; I gnaw away at an idea or concept and eventually get to the marrow, which is how that subject relates to me personally. That’s perhaps where the nostalgia comes in, what we choose to remember both personally and culturally. The stories we choose to deliberately ignore or simply forget.

Objects hold stories. They carry history, emotion, and meaning—even if we don’t always notice.

Richelle Rich

2. You’ve exhibited internationally, from London to Los Angeles—how have different cultural landscapes influenced your creative process?

I’m not sure if exhibiting changes my process, but it’s an interesting idea. I’d like to think I work from a place of introspection and concept, on ideas that transcend the geographical. By the time the work gets shown, more often than not, I have already moved on with that project or on to something new. Where I live probably shapes me more than I realize. I am more focused on American politics these days than European politics, but I think women’s rights and issues of equity are issues globally. Stories of privilege, class, religion, and gender aren’t limited to my location, but of course, however much I would like to expand it, my experience is centered as a white person in the West.

America is fascinating to me, I am constantly learning more about its history. I am inspired by the Civil Rights movement here and the evolution of the feminist movement towards a more equitable and inclusive organization. I am utterly heartbroken by the current politics, but that rage and heartbreak also galvanizes and energizes me towards solidarity and community. I respond to the physical landscape of where I am located. The vast expanse of the Mojave desert inspires me, I love being in Joshua Tree at The Art House. I am also acutely aware of the history of the land here. I am a huge fan of artist Nicholas Galantine’s work that explores those stories.

3. You describe objects as “magically contaminated” by history and memory—can you share an example of how this idea plays out in your work?

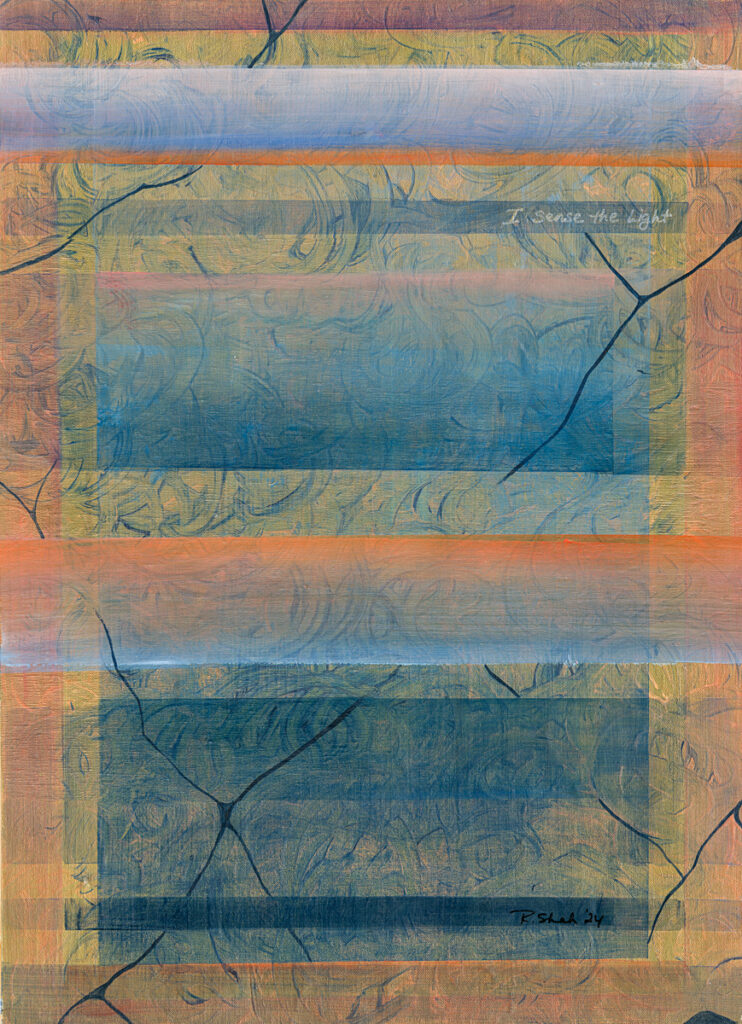

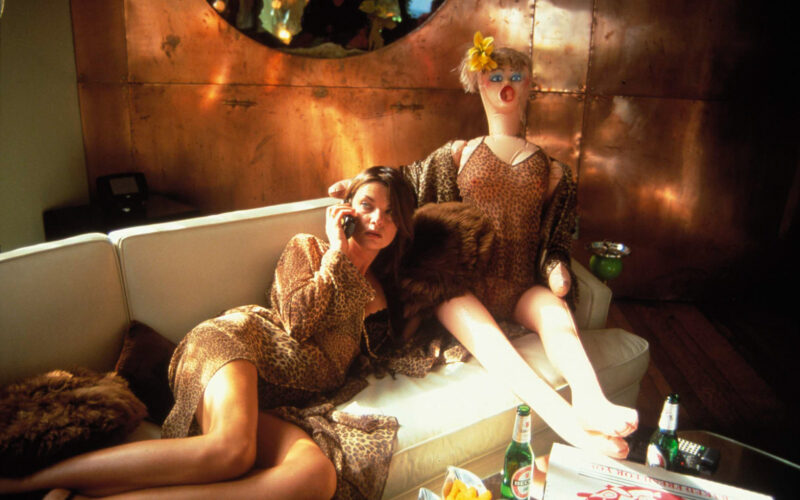

In 2020, when COVID lockdowns happened, I began working with a wonderful curator, Ceri Hand, over Zoom (she’s based in London). We talked a lot about all the objects I have in my studio, as I’m a bit of a hoarder! Over the next two years of being unable to come home to the UK, I began to examine some of those objects using my camera. Instead of performing and photographing myself as I often do, these objects became stand-ins for people, relationships, and ideas. I began to think about why I kept them and why, when people flee a place, perhaps due to climate change or war, they take seemingly worthless objects with them. During that period, I created over 200 finished works, each one a result of hundreds of shots exploring surface and angles with a macro lens.

They were seductive and unsettling and became an intimate, codified narrative of my experience of isolation during that time. During my show of these works in LA in 2023, I was lucky enough to have New York Times best-selling author and science writer Annaka Harris join me for a conversation about these ideas from a scientific perspective. She has written a fascinating book on consciousness (Called Conscious), and we debated some of these ideas. One image that particularly illustrates this idea of an object being more than it’s material body is a piece I created in 2020 entitled ‘Breakages Must Be Paid For.’ I’ll share the story of its creation… On the Isle of Wight, I have been working with an incredible glass blower, Timothy Harris, to create various sculptural commissions. Next door to his studio, there is a small smugglers and Maritime museum owned by a gentleman who also happens to be a diver. During a dive in the North Sea, he found some glass ingots (raw chunks of glass) in the hull of a 100-year-old shipwreck, once destined for the West Indies. It was perhaps intended for a stained glass window, or simply ballast, but its story has long since been washed away. He brought it to the surface and displayed it in his museum.

I selected a chunk of blue glass from his collection, and Timothy, the glass blower, took the shipwreck glass and made me a glass bowl to my specifications. I use the symbol of the blue bowl in my art practice to represent reproductive justice. So this glass bowl he created had deep personal relevance to me already, but the magic and poetry are in the traces of the sea in its translucent surface, tiny fragments of sand and shells, imperfect. The idea that something buried deep beneath the waves for so long, in the ocean for 100 years, and could be rescued, reworked in the heat of the furnace and brought back to life, to be of use, felt like alchemy in its truest form. For this photographic piece with oleander and nasturtiums, one edible and one deadly, both wild all over southern California. So this one image houses history, politics, the personal and political, and traverses literal oceans of time and place. Magic!

4. With a career spanning decades, how has your creative voice evolved, and what continues to challenge or inspire you?

It’s the same now as it always has been. Light, beauty, witnessing injustice and inequity, hearing stories, curiosity, exploration… My sense of urgency to create and to provoke thought has been constant. Making art is just how I function, it helps me to make sense of the world. I have always written and have had art writing published, but I feel I have a lot to learn, and that excites me. Working with others within the community to amplify the voices, stories, and work of other female artists feels more important than ever.

Art is a way of making sense of the world. It helps us connect the past with the present, and sometimes, it reveals things we didn’t even know we were looking for.

Richelle Rich

5. From winning major art prizes to being featured in top publications, what’s been the most pivotal moment in your journey?

In many ways, being featured in the press and having a lot of exposure and attention when I was much younger hindered my creative process for a long time. I always kept creating work, but I withdrew from showing it as I felt uncomfortable and pressured by the attention. It felt like a trap. I found the highs as distracting as the lows. I just want to make work. Remaining committed to the process, to keep following my curiosity and questioning and exploring ideas and materials, are the important things for me. Hopefully, life is long, and success comes and goes and is measured in a myriad of ways. Perhaps the most pivotal moment was relatively recent, realising I don’t have to do this alone, that I have wonderful artist friends and mentors that support my practice.

6. What advice would you give emerging women artists navigating today’s art world?

Find community, find a mentor, don’t compromise, be brave, never give up, rest, focus on making the very best work you can! Look after yourself. Other women are your allies not competition. Share your work, make friends and have fun!

Richelle Rich’s art invites us to look at the world differently. She reminds us that even the most ordinary objects can hold deep meaning. Through her work, she explores memory, history, and the power of storytelling. More than anything, Richelle believes that art is about curiosity—about asking questions and seeing beauty in unexpected places. To learn more about Richelle, click the following links to visit her profile.

Arts to Hearts Project is a global media, publishing, and education company for

Artists & Creatives. where an international audience will see your work of art patrons, collectors, gallerists, and fellow artists. Access exclusive publishing opportunities and over 1,000 resources to grow your career and connect with like-minded creatives worldwide. Click here to learn about our open calls.