👁 87 Views

About the Artist

Mara Ahmed is a Pakistani American interdisciplinary artist and filmmaker based on Long Island. She was born in Lahore and educated in Belgium, Pakistan, and the US. She has master’s degrees in Business Administration and Economics. She studied art at Nazareth College, and film at the Visual Studies Workshop and the Rochester Institute of Technology. Mara’s artwork has been exhibited at galleries in New York and California. Her documentaries have been broadcast on PBS and screened at international film festivals.

Her first film, The Muslims I Know, premiered at the Dryden Theatre, George Eastman Museum, in 2008 and started a dialogue between American Muslims and people of other faiths. Mara’s third film, A Thin Wall (2015), explores the partition of India and possibilities of reconciliation. It premiered at the Bradford Literature Festival, won a Special Jury Prize at the Amsterdam Film Festival, was acquired by MUBI India, and is currently available to watch on Amazon.

Mara gave a Tedx talk about the meaning of borders and nationalism entitled “The edges that blur” in 2017 and wrote about borderlands as liminal, hybrid spaces in “Borders can be Borderlands” (Mason Street, January 2021).

Mara is currently working on The Injured Body, a film about racism in America focusing on the voices of women of color. She produced an experimental art film Le Mot Juste [Part One] in 2021 which was selected for a juried exhibition organized by Chicago’s South Asia Institute.

During the pandemic, Mara created the Warp & Weft, a multilingual archive of stories. Audio stories, along with responses to the archive by artists, were released online in 2021. This year The Warp & Weft [Face to Face] opened at Rochester Contemporary Art Center as a multimedia exhibition including audio, video, text, and animation. Mara’s production company is Neelum Films.

Artist Statement

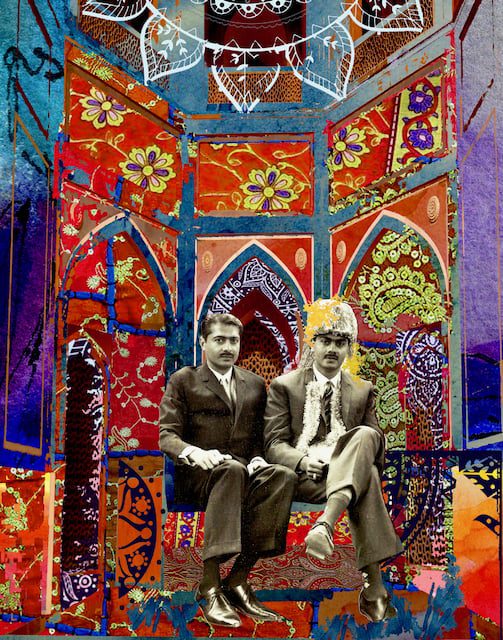

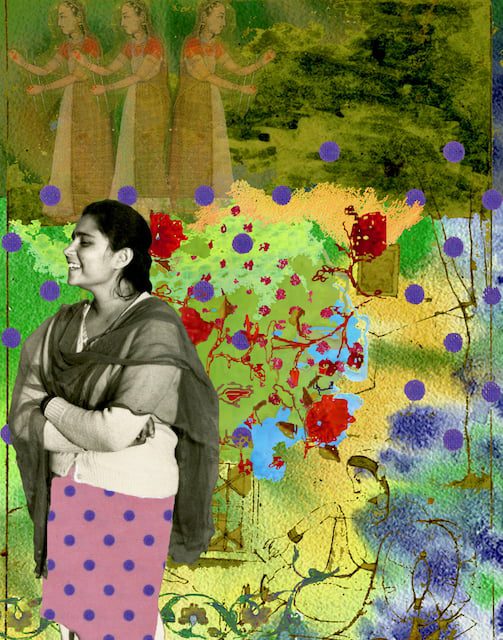

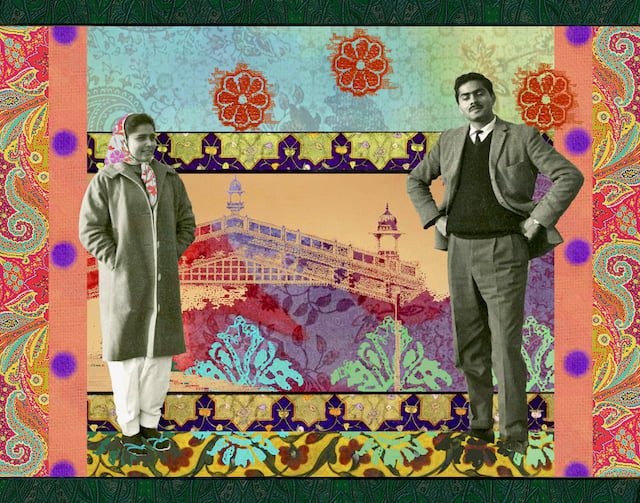

The three digital collages I have submitted are from an artwork series called “This Heirloom.”

The images are sourced from my family archive and a tribute to my parents, grandparents, and great grandparents who witnesses cataclysmic shifts in South Asian history. In 1947, the end of British colonialism heralded the creation of two independent nation states: a Hindu-majority India and a Muslim-majority Pakistan. The partition displaced some 20 million people, with estimates of up to 2 million killed.

We are South Asian Muslims. My mother’s family is from India, near Delhi. They left everything behind in 1947 (as ethnic cleansing began to alter the city’s demographics) and found refuge in Pakistan. My father’s family is from the Punjab region that became Pakistan. They were spared the bloodshed that engulfed the entire province, but their Hindu neighbors were not so lucky.

I am struck by the importance of witnessing in social justice struggles, as a corrective to ahistoricity. This is the theme of this series. I recreated my own history by using B&W photographs of my ancestors, juxtaposing them against South Asian architectural details, and bringing them to life through color and texture. Many of the shapes and patterns in this series are inspired by Pakistani fabric and embroidery.

With its intricate South Asian patterns, ancestral faces, and distant landmarks, “This Heirloom” might seem far away from the cultural milieu of downstate New York. Yet when considering the impact of segregation (racial, cultural, and economic separation) on Long Island, parallels begin to emerge.

Coming from a land fractured by colonial divisions, I attempt to resolve the implications of all these partitions. For me, art is a way to synthesize and will into existence alternative worlds. Finding my way through art helps me feel a bit more anchored, a bit more real.

How do you interpret ‘Ready to wear’ in your work?

In the 1960s, when my parents (Nilofar Rashid and Saleem Murtza) met in college, fell in love, and got married, Pakistan was still a relatively new country. My parents’ generation was the first to be solidly grounded in Pakistan. Having been recently introduced to the world at large, those who hailed from the bourgeoisie saw themselves as “progressive” and were influenced by western culture. Fashion became a way to express their newly minted national identity.

Young men adopted the Teddy Boy style of the Beatles, with boxy jackets and fitted trousers. Young women wore the traditional shalwar kameez but switched it up by making the kameez shorter and tighter, aligning it with the shift dresses they saw in fashion magazines. The bottom edge of the shalwar became narrower in keeping with men’s tapered pants. They wore head scarves and oversized shades like Audrey Hepburn and Bollywood’s Saira Banu and Mumtaz.

This hybrid sense of fashion seemed to cross borders and crack open binaries such as east and west. My mother wore a gauze dupatta over her short, dress-like kameez. She refused to give up the dainty sandals that went with her outfits but would wear socks when it got cold in Lahore. For his wedding, my father paired a gaudy sehra (headdress commonly worn by the groom) with a tailored suit. He sits proudly with his elder brother, Eitizaz Hussein.

Borders and partitions are recent aberrations. A broad span of history, that goes beyond the creation of nation states, can give us a better sense of our complex, intertwined realities, and allow us to imagine better futures.

Comments 24