This Is for Every Artist Who Thinks It’s Too Late to Begin Again I Claudia Hermosilla

👁 35 Views

At Arts to Hearts Project, we look for artists whose work feels like it came from somewhere necessary. Not planned. Not strategized. Necessary. Artists who create because something inside them demanded it, and staying silent was no longer possible.

For Issue 10 of our magazine, we’re honored to feature Claudia Hermosilla, who paints under the name Hermöcè an artist whose work stopped us the first time we saw it.

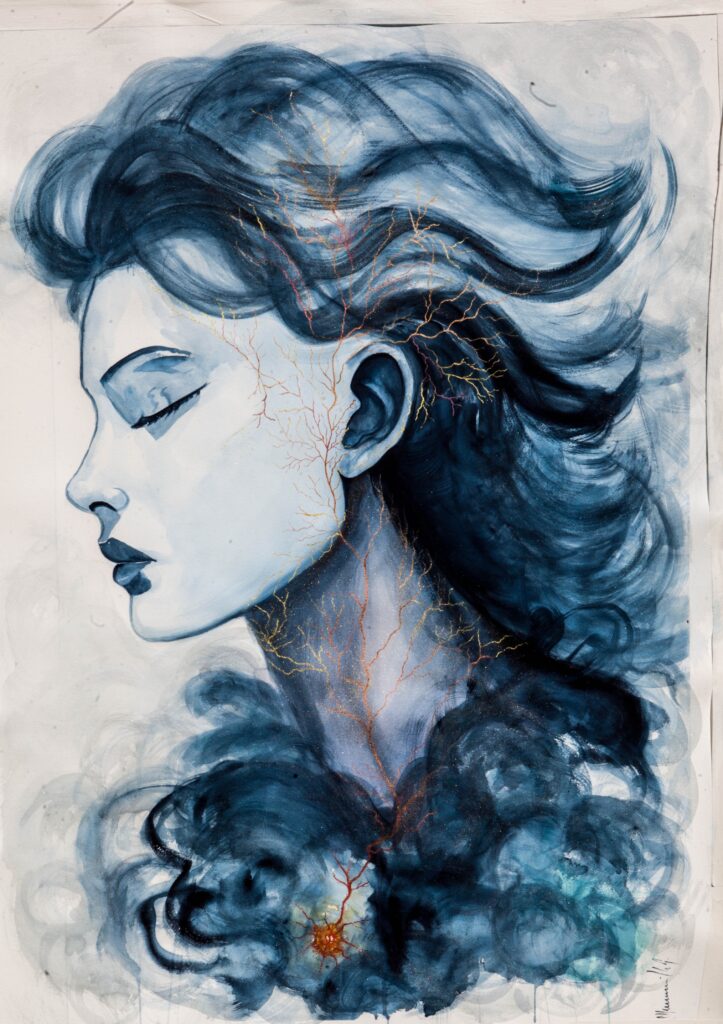

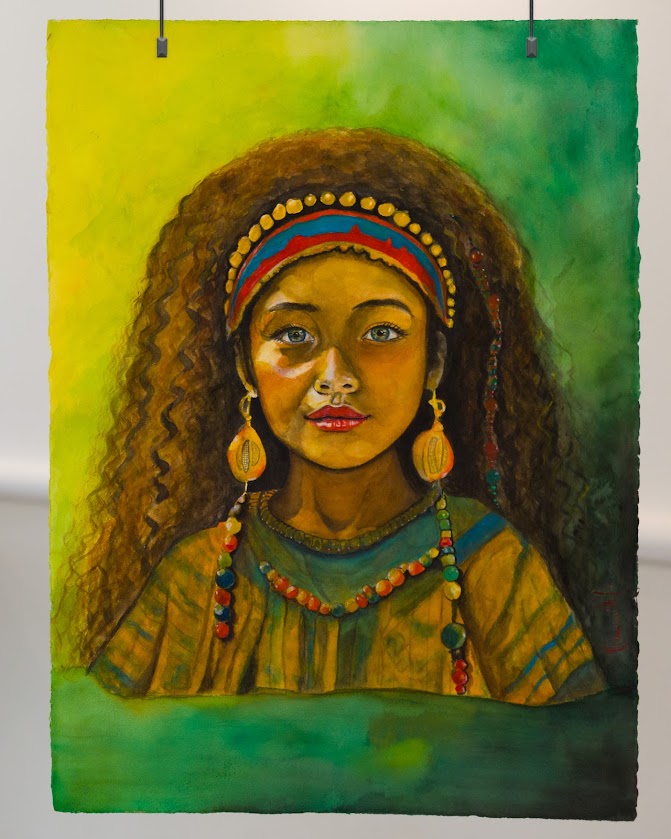

Her watercolour portraits show women in a moment most artists miss entirely: the exact instant when clarity returns. Not the triumph after. Not the before when everything was fine. That fragile second when someone exhausted, still carrying weight, still in the middle of it finds that tiny space where they remember who they are. When breath comes back. When fog lifts just enough. When something quiet inside settles.

We couldn’t look away. Because these weren’t imagined moments. You could tell she’d lived this. Known it. Painted it from memory, not theory.

When we reached out and heard her story, everything made sense. Claudia didn’t plan to become an artist. She was born one. Drew everywhere as a child—walls, notebooks, margins of schoolwork. Colors, shadows, human expressions were her first language. But she kept that part of herself silent for thirty years.

She became a forensic psychologist instead. For over three decades, she walked daily into the most vulnerable corners of human experience. Listened to stories marked by violence, pain, fragility. Entered the intimacy of people’s emotions, thoughts, hidden truths. It shaped her eye. Her sensitivity. Her understanding of the human condition. But it also led her into darkness that slowly eroded her own wellbeing.

At 56, her health collapsed. Her body and mind could no longer hold the weight of the stories she carried. Something inside her broke. She was forced to stop.

In that pause, the only thing that soothed her was painting. Watercolor felt like breathing again. It awakened a part of her that had been waiting since childhood. And through painting, something rewired inside her. Memory sharpened. Concentration returned. Fine motor skills reawakened. Mood lifted. Clarity strengthened. Everything she knew theoretically about neuroplasticity became real in her own body.

When she chose art, she chose life. She returned to the essence she had silenced. And from that rebirth, Hermöcè emerged an artistic identity rooted in women’s emotional landscapes, in quiet truths, in resilience, and in the beauty of what cannot be spoken.

Now, let’s hear from Claudia about that moment she chose art over psychology, how decades of witnessing trauma shaped her portraits, and what happens when women see themselves in her work for the first time.

I started our conversation by asking Claudia to share her background and what drives her creative philosophy.

I was born an artist, long before I ever dared to call myself one. As a child, I drew everywhere—on walls, notebooks, the margins of my schoolwork. Colours, shadows and human expressions were my first language. Yet I kept that part of me silent for decades, choosing a profession where I walked daily into the most vulnerable corners of human experience. For over thirty years I worked as a forensic psychologist, listening to stories marked by violence, pain and fragility. I entered the intimacy of people’s emotions, thoughts and hidden truths. It shaped my eye, my sensitivity, and my understanding of the human condition—but it also led me into a darkness that slowly eroded my own wellbeing. When my health collapsed, I returned to watercolor instinctively. What began as refuge became a profound restoration. Through painting, something rewired inside me: my memory sharpened, my concentration returned, my fine motor skills reawakened. My mood lifted, my clarity strengthened. Everything I knew theoretically about neuroplasticity became real in my own body. At 56, I chose light. I returned to the essence I had silenced. Art became my freedom, my voice, my stability, my life. And from this rebirth, Hermöcè emerged—an artistic identity rooted in women’s emotional landscapes, in quiet truths, in resilience, and in the beauty of what cannot be spoken. My work explores the internal moment when a woman regains herself—her clarity, her path, her pulse. Some portraits come from real women; others arrive like revelations, appearing on cotton paper as if they had been waiting for me. My role is simply to let them speak.

Hearing about that collapse after three decades, I was curious about the exact moment everything shifted. What made her leave forensic psychology and commit fully to watercolor?

I reached a point where my body and mind could no longer hold the weight of the stories I carried. After decades immersed in violence, pain and human fragility, something inside me broke. My health deteriorated, and I was forced to stop. In that pause, the only thing that soothed me was painting. Watercolor felt like breathing again. It awakened a part of me that had been waiting since childhood. One day, someone looked at my work and took it seriously—and that small gesture opened a door I had closed for years. I realised that my truest desire had always been to live in colour, water and light. Leaving forensic psychology wasn’t sudden; it was a return. A return to the artist I always was, to the language I had abandoned. When I chose art, I chose life.

The phrase “when I chose art, I chose life” stayed with me. I wanted to know how those years of witnessing trauma shaped the way she paints now. How does working with conflict and vulnerability for so long influence her portraits today?

Those years trained me to see beyond what is visible. I learned to read micro-gestures, silences, tensions, and emotional vibrations. When I paint, I don’t try to “capture” a state—I seem to enter the person’s frequency. Something resonates, and when that resonance appears, a trace remains on the paper. Not all my women come from real models. Many appear as if they arrived from a deeper place, from something that needed to be expressed without words. They reveal truth, freedom and mystery. My portraits are, in many ways, conversations with what is usually kept silent.

The idea of “entering someone’s frequency” rather than capturing them felt important. I needed to understand what reinvention at 56 actually looks like not the romanticized version, but the real one. How did that transition unfold emotionally and practically?

Emotionally, it was a return to light after years in darkness. I had to become ill—physically and mentally—to finally listen to myself. The collapse forced me to stop, to breathe, to rebuild. And watercolor became the bridge back to myself. Practically, it meant dedicating all my energy to creating, learning, experimenting and trusting. It required courage: to start over, to accept uncertainty, to show my work publicly for the first time. But each step restored something in me. Reinvention wasn’t a leap—it was remembering who I had always been.

“Reinvention wasn’t a leap it was remembering.” That distinction made me wonder about her process. Her portraits capture such a specific moment—when someone regains clarity. How does she recognize that moment when she paints?

It isn’t analytical. It emerges naturally. I begin with an idea, but the deeper emotional expression appears only at the end—almost without me noticing. Watercolor allows that freedom: the emotion surfaces, not through control but through letting go. There are rules, techniques and challenges, yes, but the essential moment comes when I allow imperfection, risk and intuition. Painting clarity requires vulnerability from me as well. I follow the water, the accident, the luminosity. When the portrait breathes, when something quiet inside me settles—that’s when I know the moment has appeared.

Hearing her talk about following the water, the accident, the luminosity I was curious about her approach to neuropsychology. It’s not metaphorical, it’s literal. How do those two fields meet in her creative process?

They meet in my body first. After my health collapsed, painting became neurological rehabilitation. As I worked with colour and water, I experienced firsthand how attention, memory, emotional regulation and fine motor circuits reorganized themselves. What I had studied for decades became embodied truth. That is why neuropsychology is now part of my Hermöcè Method. For me, watercolor is not only aesthetic—it is sensory, cognitive and emotional activation. It is a way of restoring presence, rebuilding inner order and inviting the brain to reconnect with itself. Art transformed me from the inside out, and now it informs how I create.

That connection between art and neurological healing stayed with me. She’d mentioned women seeing themselves in her work, and I wanted to know more about those moments. What reactions stay with her?

Women often approach my work in tears. They see themselves in the portraits moments of exhaustion, resilience, rebuilding, or awakening. Many tell me they feel “seen” or “spoken to” without words. What moves me most is when they say:

“I thought it was too late for me. Your story makes me want to begin again.”

Those encounters are my greatest inspiration. Painting women is a way of honouring our shared silences, our invisible strengths, and the inner landscapes that shape who we are.

Wrapping this conversation with Claudia, one thing I realized: most stories about starting over treat it like becoming someone new. Shedding your old self and building from scratch. But Claudia’s story is different. She didn’t become an artist at 56. She returned to being one. She’d been drawing on walls and notebooks since childhood. Colours and shadows were her first language. She just silenced that part of herself for thirty years.

And here’s what strikes me: those thirty years weren’t wasted. Working as a forensic psychologist entering the intimacy of people’s emotions, reading micro-gestures and silences that trained her eye in ways art school never could. She learned to see beyond what’s visible. To enter someone’s frequency rather than capture their appearance. That skill shapes every portrait she makes now.

But she couldn’t access it through art until she stopped using it professionally. She had to break first. Her body refused to hold any more weight. Something inside her collapsed. And in that forced pause, watercolour became the only thing that soothed her.

What she described wasn’t just creative expression. It was neurological rehabilitation. She experienced firsthand how painting reorganized her attention, memory, emotional regulation. Everything she’d studied theoretically about neuroplasticity became embodied truth. Art didn’t just give her a new career. It rewired her brain. It gave her back herself.

That’s why her portraits feel different. She’s not painting what resilience looks like from the outside. She’s painting the exact moment it begins from the inside. That instant when clarity returns not because everything’s fixed, but because something quiet settles. She paints it intuitively. Following the water, the accident, the luminosity. And when the portrait breathes, when something quiet inside her settles that’s when she knows the moment has appeared.

Here’s what Claudia taught me: sometimes you have to break completely before you can return to yourself. Sometimes the thing that nearly destroys you is exactly what qualifies you to create the work only you can make. And sometimes reinvention isn’t about becoming new it’s about remembering who you always were beneath everything the world tried to make you.

Follow Claudia from the link below to see her beautiful work and witness those exact moments when clarity returns.