How Juliano Mazzuchini Turns the Human Figure Into Presence and Gesture

👁 67 Views

Some creative paths begin with a sudden decision, a moment of clarity that changes everything. Juliano Mazzuchini’s journey, however, began long before he ever thought of himself as an artist. It began in a way of noticing in the quiet of the Brazilian countryside, in the rituals that shaped his childhood, and in the early realisation that the human body can carry stories that words are too small to hold. Growing up in Jacareí, surrounded by nature and a simple rhythm of life, Juliano found his first doorway into expression through theatre. It was a world unlike anything he had known at home: a world where silence had weight, gestures carried truth, and imagination became a shared space between people.

Those early experiences stayed with him. In the intimate distance between actor and audience, in the tension before a line is spoken, in the fragile magic that makes fiction believable Juliano sensed something he couldn’t name yet. A kind of mystery. A kind of presence. A way of paying attention to life. These seeds would eventually grow into the language he now uses on canvas.

As part of this week’s Best of the Art World series, we are honoured to share Juliano’s story one that winds through multiple disciplines, cities, and inner terrains, yet remains anchored in the same question: What does it mean for something to come alive?

His formal training at the Escola Livre de Teatro introduced him to epic theatre and Brechtian structures, where storytelling is less about illusion and more about intention, clarity, and the power of the body as a site of meaning. Later, returning to Jacareí to act and direct, he sharpened his understanding of presence how tension builds, how a gesture can transform a room, how a single movement can carry an emotional truth. In those years, Juliano wasn’t just making theatre; he was learning how to watch, how to listen, how to work with the invisible layers that surround every moment.

The turning point arrived in Buenos Aires, though it didn’t feel dramatic at first. He stepped away from theatre, began painting, and discovered something surprising: he had not left a discipline behind; he had simply shifted the stage. Painting, he realised, could hold the same intensity he once sought in performance. The same search for the exact instant when something “happens.” The same fascination with presence, tension, and the fragile space between revelation and concealment. The body remained central only now, instead of performing in front of others, it became image, gesture, and material.

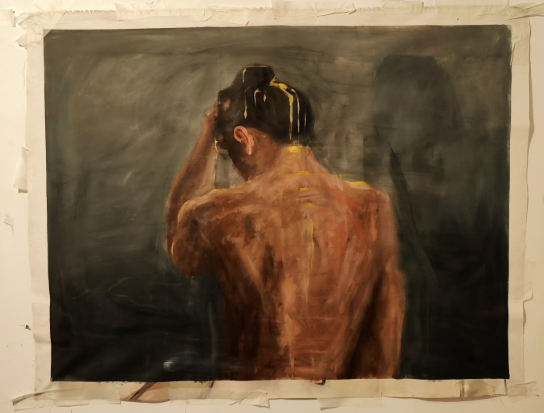

Today, Juliano’s practice moves toward what he calls the “unspeakable.” His paintings are not narrative; they are atmospheric. They hold the moment before meaning becomes clear the suspended breath, the charged silence, the feeling that something is about to reveal itself yet chooses to remain hidden.

His process is its own kind of performance. He often photographs his own body, or, at times, his wife’s, not to document identity, but to access a physical state that later dissolves in the painting. The body becomes a passage rather than a subject, a familiar starting point that transforms into something unrecognisable once it enters the canvas. His paintings unfold in long, intense sessions, yet the days leading up to them, the waiting, the watching, the quiet attention are equally part of the work.

Juliano’s canvases read like scenes without scripts: gestures suspended in a moment of possibility, bodies partly formed and partly dissolving, atmospheres thick with a kind of emotional charge. They invite viewers not to interpret, but to sense to step into the same space of uncertainty that fuels his practice. The paintings don’t answer questions; they echo them. They carry mystery without trying to solve it.

Let’s step into Juliano Mazzuchini’s world and explore the gestures, tensions, and quiet revelations that shape his evolving practice.

Can you share your background and how your journey from growing up in Jacareí, to working in theatre, and now living in Buenos Aires has shaped the artist you are today?

I grew up in Jacareí, in the countryside of São Paulo, surrounded by nature and a simple way of life, where I had my first contact with art, especially theatre. That’s where I discovered a form of expression that didn’t exist within my family. Later, I moved to Santo André, where I deepened my studies at the Escola Livre de Teatro, focusing on epic and Brechtian theatre, which greatly influenced my research. I then returned to Jacareí, where I acted and directed with a local theatre group, and it was during that period that I began painting. When I moved to Buenos Aires, I left theatre and began to dedicate myself entirely to painting.

What was the moment you knew you had to fully dedicate yourself to painting? Was it a gradual shift from theatre, or did something spark a clear turning point?

When I moved to Argentina, I stopped working in theatre and started painting. Over time, I realized there was a continuity between what I had been doing on stage and what I was seeking through painting. My interest in the body, presence, and the figure remained — it just shifted mediums. In theatre, the body is in front of the audience; in painting, it becomes image. But the investigation is the same: gesture, tension, and the moment when something happens. I realized that painting could hold the same kind of intensity and truth I used to look for on stage. That was the turning point. I understood that even in silence there was a form of performance — the body was still there, now mediated by paint, surface, and time. In a way, I continue doing the same work, only through another form: the poetics that once lived in the actor now lives in the painter.

Early on, you were surrounded by religious practices and rituals. How do those memories of symbolism, mystery, and sacredness continue to echo in your current work?

Growing up in that context awakened in me an interest in mystery and in the invisible that exists within rituals. More than the religiosity itself, I was always drawn to the atmosphere created there — a sense of tension, silence, and expectation before the unknown. In theatre, I began to notice something similar, though of a different nature: a collective belief that allows fiction to exist. There is a kind of shared faith between actors and audience — a silent agreement that what is being performed is both real and invented at the same time. That fragile balance always fascinated me. In painting, this perhaps appears as an attempt to approach what cannot be named. Sometimes I think painting is a way of returning to that same state of suspension, where something seems about to reveal itself but never fully does. I’m not sure exactly what it is — maybe it’s just the desire to touch what is out of reach, what remains silent within the image.

You’ve said that you search for the “unspeakable” in painting. What does that mean to you and how do you know when you’ve touched it in your work?

When I talk about the “unspeakable,” I’m thinking about what can’t be fully translated into words — what remains after everything that can be said has already been said. Painting, for me, has the ability to hold that kind of space — the interval, the doubt, what doesn’t resolve. Sometimes I feel I get close to it when the painting begins to surprise me, when something appears that I didn’t plan or expect. It’s the moment when control fades and the image seem to gain its own autonomy. I’m not sure it’s possible to truly “find” the unspeakable — maybe all one can do is move toward it, keeping open that tension between what is revealed and what stays hidden.

In your painting “Dimitto” (2022), the atmosphere feels both fragile and powerful. Can you share the story of how that piece came to life, and what it means to you personally?

“Dimitto” (2022) is part of an ongoing investigation into gesture, inspired by chirology — the study of gestures used to emphasize rhetorical appeals. As in theatre, where gestures must be potent and expressive, in this work I tried to expand that idea within painting, allowing meaning to emerge through the scale and amplitude of the gesture itself. On a more personal level, I see this piece as a nod to the narrative possibility of theatre transposed into a pictorial gesture. It’s as if the gesture, once performed in a scenic space, now finds another kind of presence on the canvas — silent, yet still charged with action and intention.

Shifting from theatre to painting must have come with doubts and challenges. What fears did you have to face in making that transition?

In the beginning, my main fear was losing the collective space. In theatre, everything happens in a group — there’s exchange, rhythm, immediate response. When I started painting, I was confronted with the silence and solitude of the studio, which demanded a new kind of presence. I had to understand that the isolation of the studio could also be productive — a space for listening and attention. Another challenge was coming from an essentially narrative language. In my theatre work, everything started from a structure of action and conflict; in my painting, that disappears. My work may suggest a story, but it isn’t narrative. I believe painting operates in a different time, in a different logic — it doesn’t tell, it contains. This shift was challenging but also liberating. Over time, I realized that painting allowed me to deal with the same body and the same intensity, only in a more open, less linear way.

Many of your works are created in one intense session. How do you prepare yourself mentally, emotionally, even physically for that kind of concentrated painting?

I’m not sure there’s a defined kind of preparation. Sometimes I spend days just looking at the canvas, trying to understand if it’s the right moment to start. And that doesn’t mean nothing is happening in fact, a million things are happening during that time. That interval is also work; it’s also painting. It’s a moment when everything feels suspended, as if something were taking shape before the gesture itself. Other times, things happen unexpectedly, almost like a physical need. The painting seems to ask to happen. I think it has more to do with being available than being in control staying attentive to the moment when something might appear. It’s not as if painting only comes in a moment of inspiration, or that before that inspiration I wouldn’t know what to paint I always know what to paint. The question isn’t what, but how. Painting depends on finding the right tone, the right rhythm, and that can’t be forced. Maybe the preparation lies in this exercise of attention. I learned in theatre that the body knows before thought does. I try to bring that into painting: to quiet the mind so the gesture can come from somewhere else. It’s not a rational decision it’s more like listening. Sometimes the focus breaks, sometimes nothing happens and that’s okay. I still don’t fully understand what makes one painting happen with such intensity and another not. Maybe it’s just a matter of time, of being present when something decides to appear.

Have you ever experienced a time when you felt lost in your practice? How did you find your way back?

Yes, many times and honestly, I think I still remain in that state of uncertainty. I’m not sure there’s a “path” to be found again. Sometimes I feel that painting happens precisely in that place of doubt, when nothing is too defined. When I feel truly lost, I tend to return to the artists who have inspired me both past and contemporary ones. And that doesn’t necessarily mean looking at paintings; sometimes it’s in a film, a song, a book, or even a conversation. It’s more about reconnecting with a certain vibration, a way of seeing, than seeking direct references. Sometimes a gesture, a word, or a sound is enough to remind me why I began. I still don’t know if this uncertainty is an obstacle or a kind of driving force. Maybe it’s both. What I’ve learned or am still learning is not to try to get out of it too quickly. Sometimes it’s in that interval, when I don’t know what to do, that something new begins to appear.

Your process often involves photographing your own body and then transforming those images through painting. What does it mean for you to use your own body as material, and how does that change the intimacy of your work?

Using my own body came naturally. At first, photographing myself was simply a way to produce images to paint a practical, almost technical resource. Over time, I realized there was something beyond the act of documentation: I was performing for my own paintings. The gesture, the gaze, the posture carried a scenic intention, even without a defined character. This performative dimension gradually became part of the process — a kind of preparation before painting takes place. Sometimes I also photograph my wife, and those images bring a different energy — a shared presence where gesture and gaze move between the two of us. Later, these bodies change completely in the painting. Sometimes I can no longer recognize them. It’s not a self-portrait, nor a study of us. It’s more an attempt to understand the body as a space of passage — something that transforms, that dissolves. I often wonder whether using my own body (or that of someone so close) makes the work more intimate or more distant. Maybe both. They are familiar bodies, but once they enter the painting, they no longer entirely belong to us.

Your art has been shown in Brazil, Argentina, and beyond. How do different cultural contexts affect how people respond to your work?

I’m still not entirely sure how cultural context changes the way my work is perceived. I have the impression that there are differences, but I don’t always understand where they come from. In Brazil, I feel at home, but sometimes I have the sense that my work doesn’t as if it’s still finding its place within the local circuit. In Argentina, the dialogue has always felt a bit fragmented, even though it was an important place for my development as an artist. There are exchange and interest, but also a certain mismatch of timing and references. Overall, I feel that my work communicates with the contexts in which it’s shown with the spaces, the audience, and with my peers. Still, when it comes to the market, I’ve noticed that it has been more readily received elsewhere, outside Brazil and Argentina. I’m not entirely sure why — maybe it’s a matter of context, timing, or simply of encounter.

Do you feel a responsibility for your art to speak to wider social or spiritual questions, or is it more about personal exploration for you?

That’s a question I honestly don’t have an answer to. My conscious intention doesn’t point directly in those directions, but my formation as an individual the experiences I’ve had, the context I come from, the references that shaped me probably end up crossing the work in some way. I think that happens without any deliberate effort.

I don’t see painting as a vehicle for a message, but it inevitably carries something of who I am and of the time I live in

Maybe only the painting itself could really answer that question. (laughs)

What advice would you give to artists who are just beginning their creative journey especially those exploring more than one discipline, like you have?

I’m not sure I’m in a position to give advice, but maybe I can share something that has helped me. I think it’s important to have references — and not only within the language you’ve chosen. Read the classics, watch classic films, listen to music from different genres, go to the theatre, read poetry. All of that shapes the way you see things and builds a foundation that quietly sustains the work, even when it doesn’t seem directly connected to it. And maybe it’s also good to remember that you’re not reinventing the wheel, but act as if you were. I’m not sure why, but that mix of humility and delusion seems necessary. It keeps the work moving, even when you don’t fully know where it’s going.

Wrapping our conversation with Juliano, we’re reminded that painting can be an act of listening not to the world outside, but to the quiet, charged space between thought and gesture. His work feels like a continuation of something ancient: the ritual of looking closely, the belief that an image can hold the weight of a moment, the sense that what matters most lives just beyond language.

Juliano paints with a performer’s sensitivity, a director’s awareness of tension, and a seeker’s devotion to mystery. His figures do not tell stories; they contain them. They inhabit a space where presence feels heightened, where the unsaid becomes the central force in the room. His gestures, born from photographs of his own body or the shared intimacy of photographing his wife dissolve into something universal, something that transcends identity and moves toward pure expression.

What stands out most is his willingness to stay in uncertainty. To not rush clarity. To trust that doubt, silence, and suspension are part of the work not obstacles to it. In a world that demands constant output and certainty, Juliano’s practice is a quiet resistance. A reminder that art doesn’t need to declare; it can simply be, holding the complexity of what cannot be named.

As he continues evolving across countries, disciplines, and inner terrains, his paintings invite us to slow down, to look again, to sit with the image until it begins to speak in its own time. His work is not loud, but it stays with you the way a gesture stays in the body long after the performance has ended.

Follow Juliano Mazzuchini to witness an artist who moves with intuition, presence, and profound sensitivity someone who paints not answers, but the enduring mystery of being human.