The Work That Surprises You Is Usually Better Than What You Planned I Daniel Andersson

👁 83 Views

At Arts to Hearts Project, we’ve always been drawn to artists who do things differently. Not different for the sake of being different, but different because the conventional path never worked for them in the first place. Artists who find their own way in, build their own language, create work that doesn’t fit neatly into existing categories.

Those are the artists we believe deserve space in Best of the Art World. And that’s exactly why we reached out to Daniel Andersson, who creates under the name Vexed Works.

When we first encountered his digital collages surreal, unsettling imagery that sits somewhere between beauty and nightmare, nostalgia and dread we knew immediately this was work that refused to play by the rules. Not rebelliously. Just honestly.

Before you get to know Daniel through this interview, let me tell you what drew us to his practice.

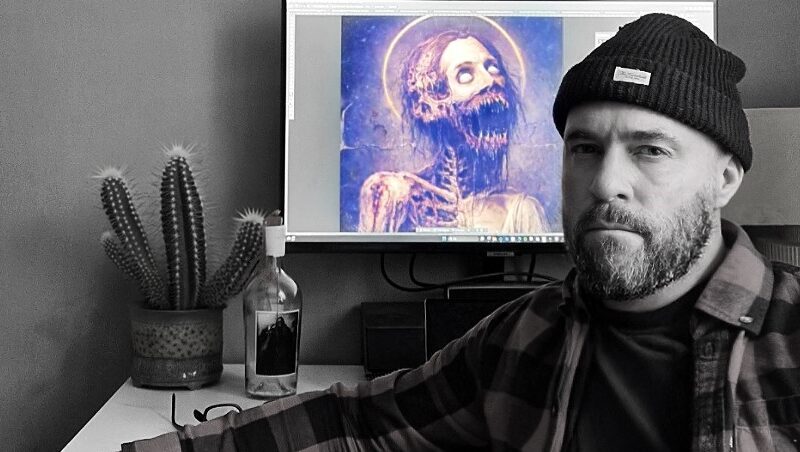

Daniel creates digital collages that do something most digital art doesn’t: they unsettle you. Not through shock or gore or obvious provocation, but through something quieter and more effective. He takes familiar imagery folk motifs, domestic objects, retro textures, Victorian calm and bends them until they feel slightly haunted. Like they’ve slipped out of their expected roles. They remain recognizable, but something in their posture is off. A quiet wrongness that lingers. And that wrongness? It’s not accidental. It’s the entire point.

Daniel’s path into visual art began with discovery and access. His older brother introduced him to early digital tools a Commodore 64, an Amiga 500 and suddenly making art became possible in ways traditional methods never allowed. He dove into pixel art with Deluxe Paint and its revolutionary 256 color palette, got involved in the Amiga demo scene collaborating with programmers and musicians to create multimedia work visuals woven into sound and code.

That’s a different origin story than most visual artists have. And it shaped everything about how he works.

As technology evolved, he moved to PC and began working with what would eventually become Adobe Photoshop, which has remained central to his practice ever since. But in the late ’90s and early 2000s, his creativity expanded into the physical world too street art, graffiti, screen printing, textile design. Bringing ideas to life on walls, fabric, clothing. Raw, tactile, immediate.

That hybrid approach digital precision meeting physical messiness that’s still what makes his work breathe. His name, Vexed Works, isn’t just branding. It’s accurate. The word “vexed” carries exactly the emotional charge he’s after: tension, disturbance, complexity. His collages aren’t just images. They’re emotional landscapes where beauty is always threaded with unease.

His process is split between two modes. Sometimes he begins with precise vision an emotion to summon, a metaphor to chase. He becomes a curator, sifting through archives with surgical focus, searching for the one image whose texture and composition align perfectly with the story forming in his mind.

But then there are the accidents. The moments where he stumbles across an image that was never part of the plan but suddenly feels essential. And here’s what caught our attention: he says those spontaneous pieces often become his most powerful work. They carry raw, instinctive energy that emerges when he stops overthinking and simply responds.

The transformation in his work begins with intention a mood to unsettle, a symbol to fracture, a familiar form to push until it trembles. That part is deliberate. But the uncanny the moment where the image tilts into something stranger, truer usually arrives on its own. A glitch. A shadow. A texture behaving like it has its own pulse.

His work taps into something between the personal and the collective. He’s not illustrating specific fears or decoding tidy psychological messages. He’s tapping into a current that runs underneath both, and the images become the place where those currents overlap. Inner landscape and broader societal anxieties blurring together.

Let’s get to know Daniel through our conversation with him exploring how digital tools opened new creative possibilities, why emotional honesty makes imagery resonate, what happens when spontaneous discoveries shape finished work, and how ambiguity creates depth and keeps work alive.

Q1. Can you share your background and how your journey brought you to creating surreal digital collages under the name Vexed Works?

My Instagram handle began as VXD_GFX—short for Vexed Graphix. It had a sharp, abrasive edge, but over time I realized it didn’t fully capture the atmosphere I was building. The word “Vexed” stayed with me, though. It carried the emotional charge I kept returning to: tension, disturbance, complexity. It felt like the perfect descriptor for the surreal, uneasy terrain my collages inhabit. Eventually the name evolved into Vexed Works, a broader identity that reflects the full range of what I create across mediums and platforms. It speaks to the essence of my approach: work that unsettles, provokes, and lingers. My collages aren’t just images—they’re emotional landscapes where nostalgia rubs against nightmare, and beauty is always threaded with unease. Vexed isn’t just a word; it’s the mood that drives everything I make. My path into visual art started early, thanks to my older brother and the glow of a Commodore 64 and an Amiga 500. At first I was more interested in Sega and Nintendo than computers, but that changed when he introduced me to C64 Paint, a simple pixel‑art program that opened a door I didn’t know existed. I was never naturally gifted at traditional drawing or painting, so digital tools felt like a revelation—an accessible way to build worlds. The Amiga 500 was a turning point. With Deluxe Paint and its then‑revolutionary 256‑color palette, I dove deeper into pixel art and eventually into the Amiga demo scene. I collaborated with programmers and musicians to create multimedia demos—visuals woven into sound and code. As technology moved forward, so did I. I transitioned to PC and began working with more advanced software like Photostyler, which later became Adobe Photoshop. Photoshop has been central to my workflow ever since, alongside Illustrator for logo and print work. In the late ’90s and early 2000s, my creativity spilled into the physical world. I threw myself into street art, graffiti, screen printing, and textile design, bringing ideas to life on walls, fabric, and clothing. It was raw, tactile, and imperfect—everything digital art wasn’t—and it shaped the hybrid approach I still carry today.

Q2. Your digital collages and photo manipulations are often described as intense and uncanny, occupying a space between beauty and the disturbing. How do you think about that balance when you’re creating?

There’s a point where an image stops being just pretty or just unsettling and starts to feel alive—that charged, uncanny hum is what I’m always chasing. For me, beauty is the entry point. If something is only disturbing, people turn away. But if the colors, composition, or familiarity pull them in first, the uncanny can slip in after—the delayed realization that something isn’t quite right. The unsettling parts only work when they’re emotionally honest. I’m not interested in shock; the strangeness has to come from something real—grief, longing, nostalgia, fear. That’s what gives the image weight. I also want the piece to feel like it remembers something. A portrait that knows more than it shows, a landscape with history in its bones. That sense of memory is what makes the beauty feel haunted. In the end, it’s like tuning a frequency. Too beautiful and it’s decorative; too disturbing and it repels. But when both tones vibrate together, the image becomes magnetic—something you don’t just look at but feel.

Q3. Your art often repurposes existing imagery into new, surreal visuals. How do you choose source material, is it intuition, concept, mood, or something else that draws you in?

There are days when I begin with a precise vision — an emotion I want to summon, a metaphor I’m chasing, a narrative I’m intent on shaping. In those moments, I become a curator. I sift through archives and personal collections with almost surgical focus, searching for the one image whose texture, shadow, and composition align perfectly with the story forming in my mind. Music, daily life, and the quiet rhythms around me all feed into that deliberate hunt. But then there are the unexpected moments — the ones where I stumble across an image by accident. A forgotten photograph, a stray texture, a visual fragment that was never part of the plan yet suddenly feels essential. These discoveries hit somewhere deeper. They shift my direction, reshape the concept, or spark an entirely new idea. It feels less like I found the image and more like it found me. Strangely, those spontaneous pieces often become my most powerful work. They carry a raw, instinctive energy — the kind that emerges when I stop overthinking and simply respond to what the image offers. The process becomes less about control and more about listening, letting the composition guide itself. It’s a reminder that creativity isn’t only built through precision or planning. Sometimes it thrives in the unexpected, in the moments when inspiration slips in sideways and leads me somewhere I never intended to go.

Q4. Many of your collages seem to play with hidden fears or unresolved tensions beneath their surfaces. Do you think your work is reflective of inner psychological landscapes, collective anxieties, or both?

It’s both — but not in a neat, binary way. When I build a collage, I’m not trying to illustrate a specific fear or decode some tidy psychological message. It’s more like I’m tapping into a current that runs underneath both the personal and the collective, and the images become the place where those currents overlap. The inner landscape is always there — the half‑formed thoughts, the quiet dread, the things that don’t announce themselves but still shape the atmosphere of a piece. But at the same time, I’m pulling from symbols, textures, and tensions that feel culturally charged. The work becomes a kind of shared dream space where my own subconscious and broader societal anxieties blur together.

So the fears aren’t just mine, and they’re not just ours. They’re the ones that sit in the in‑between the unnamed, the half‑felt, the things we sense before we articulate.

That’s why the tension in the images feels familiar even when the composition is surreal — it’s drawing from a psychological vocabulary we all recognize, even if we don’t consciously speak it. In that sense, the collages become mirrors with multiple layers: one reflecting inward, one outward, and one catching the strange shimmer where those two reflections meet.

Q5. Your work often destabilizes familiar imagery into the unexpected or uncanny. How much of that transformation is planned, and how much emerges through the editing process itself?

My work begins with intention: a mood I want to unsettle, a symbol I want to fracture, a familiar form I want to push until it trembles. That part is deliberate. But the uncanny—the moment where the image tilts into something stranger, truer—usually arrives on its own. A glitch, a shadow, a texture behaving like it has its own pulse. I don’t plan those. I recognize them. Editing becomes a conversation rather than a correction. The piece pushes back, reveals things I didn’t consciously aim for. I follow the anomalies that feel alive and discard the ones that don’t. In the end, the final image is often more honest than the original idea. The uncanny is just the subconscious leaking through the seams.

Q6. Many artists working online grapple with the tension between personal expression and algorithmic visibility. Does the way your art circulates on social media shape what you create, or do you intentionally resist that influence?

I think every artist online feels that gravitational pull between personal expression and algorithmic visibility. You can resist it, you can ride it, but you can’t pretend it isn’t shaping the terrain. On one side, the algorithm rewards recognisable styles, quick reads, emotional punch, and repetition. Even when you try to ignore it, you catch yourself adjusting pacing, cropping, or colour just because you’ve internalised what tends to “perform.” On the other side is the inner compass — the urge to make work that’s slower, stranger, more symbolic, more yours. Some artists lean into the algorithm strategically; others deliberately break its expectations. Most of us drift between the two depending on the project or the season. In my own practice, mood and symbolism matter more than virality, but I’m not naïve about visibility either. I’ll use the current when it helps, but I don’t let it steer the ship. The real challenge is staying open enough to adapt without letting the machine decide what I make.

Q7. A number of your pieces evoke a sense of ambiguity neither comforting nor frightening, but deeply evocative. Do you see ambiguity as a creative tool in your work’s expressive language?

I’m not interested in telling the viewer exactly what to feel, or in steering them toward comfort or fear. I’m after that charged middle ground where meaning flickers — where something feels familiar but not fully nameable, symbolic but not decoded, intimate yet estranged. For me, ambiguity is a way of keeping the image alive. When everything is spelled out, the piece dies the moment the viewer “gets it.” But when the emotional signal is unstable — when the mood shifts depending on how long you look, or what part of yourself you bring to it — the work becomes a kind of mirror. It invites projection, interpretation, even contradiction. I use ambiguity deliberately: in lighting that suggests two moods at once, in symbols that resist a single reading, in faces that hold both serenity and unease. It’s not about obscuring meaning; it’s about widening the emotional bandwidth. The piece becomes a conversation rather than a statement. So yes — ambiguity is absolutely a creative tool for me. It’s the tension that keeps the work breathing, the space where resonance happens, the place where the viewer steps in and completes the image.

Q8. The digital medium offers limitless combinations and permutations. Have you encountered moments where choice overload becomes a challenge, and how do you navigate that creatively?

I view the digital medium as both a gift and a maze; its boundless possibilities are exhilarating, but they also make choosing a direction the true challenge. When every path is viable, the act of selecting one becomes an artistic decision in itself. Over time, I’ve come to see choice overload not as a flaw but as a meaningful signal — a reminder that the work is alive, full of potential, capable of unfolding in several compelling ways. That moment of tension, where multiple futures coexist, is precisely where creativity sharpens and thrives.

Q9. Your pieces often disrupt familiar visuals into something uncanny or uncanny-beautiful. What do you hope viewers feel or question when they encounter that tension?

There’s a charge when something almost makes sense but doesn’t—a brief, electric hesitation where recognition falters. That’s the space I work in. I take familiar images—folk motifs, domestic objects, retro textures—and bend them until they feel slightly haunted, as if they’ve slipped out of their expected roles. They remain recognizable, but something in their posture is off, a quiet wrongness that lingers. I’m after that flicker of doubt, the moment you question your own memory or instinct. The work becomes a mirror, not of the image itself, but of your reaction to it—your discomfort, your curiosity, your attraction. In that tension, myth and the present begin to bleed together. Old symbols surface through digital skin; everyday objects carry the weight of rituals you’ve never learned but somehow remember. I’m not interested in tidy answers or fixed interpretations. The ambiguity is intentional. I want you to stay in that unresolved space, to let the image breathe and shift, to feel the pull of something both ancient and newly made.

Q10. Looking at the body of work you’ve created so far, what do you see as the central thread connecting the pieces thematically, emotionally, or conceptually?

When I look at the work I’ve been making, there’s a clear thread running through it: I’m drawn to the tension between beauty and unease — that place where something luminous starts to feel haunted. I keep circling the emotional in‑between. Serenity with a crack in it. Nostalgia with teeth. Humor that accidentally reveals something human. A saint glowing with devotion but shadowed by dread. A Victorian calm interrupted by impossible holes. My symbols behave like living things — crowns, ribbons, candles, skulls, flowers — modern shapes wearing ancient bones. I’m not retelling myths; I’m building new ones out of familiar emotional grammar. Every image hints at a larger story just outside the frame. Something has happened, or is about to. Something is being concealed. I like when the world feels bigger than what you can see. And visually, I’m always balancing realism with disruption. I push detail and atmosphere, then break it on purpose — a small fracture that shifts the whole mood. What happens when the familiar becomes strange — or the strange becomes familiar? That’s the pulse behind all of it.

Q11. What advice would you give to emerging artists who want to develop a distinctive artistic voice in the realm of digital collage or experimental visual practices?

Developing a distinctive voice in digital collage isn’t about locking yourself into a single style; it’s about shaping a way of seeing. It grows out of the images you collect, the textures and fragments that stay with you for reasons you can’t always explain. The things that haunt you, confuse you, or feel slightly wrong eventually form a visual vocabulary that’s unmistakably yours. Constraints help sharpen that identity—limiting your palette, your sources, or your tools forces intention, and intention becomes recognizability. The process itself should stay wild and exploratory: destroy and rebuild, mix analog with digital, push an image until it nearly collapses and then pull it back. Those accidents and detours become part of your signature. The rest is repetition and obsession. Make endlessly, revisit old pieces, notice what keeps returning without your permission. That’s where your voice lives. Writing alongside the images—notes, fragments, titles, process thoughts—helps clarify intention and sharpen vision. And when you share the work, pay attention not for validation but for resonance: what feels alive, what feels forced, what others respond to. All of it becomes part of the ongoing excavation that shapes who you are as an artist.

Wrapping my conversation with Daniel, I kept coming back to something he said: the final image is often more honest than the original idea. The uncanny is just the subconscious leaking through the seams. That hit me hard because it’s the opposite of everything we’re taught about artistic success.

We’re told mastery means control. That great artists execute vision with precision. That the closer your finished work matches what you planned, the more skilled you are. The entire creative industry operates on this assumption: know what you want, plan meticulously, deliver exactly that.

But Daniel’s built an entire practice on the opposite principle. He’s saying the best work happens when you stop trying to control the outcome and start listening to what wants to emerge.

And honestly? Looking at his work, he’s right.

What fascinates me most is how accidents keep becoming essential in his practice. He’ll start with precise vision, curating images with surgical focus, chasing a specific metaphor. But then he stumbles across something by accident. A forgotten photograph. A stray texture. Something that was never part of the plan.

And those unplanned pieces? They’re often his strongest work. They carry this raw, instinctive energy that you can’t manufacture through careful planning.

Most artists would see that as failure of discipline. I used to think that way too. But watching how Daniel works, I’m starting to understand it’s actually a more sophisticated form of discipline. It’s the discipline to recognize when something true is emerging and get out of its way.

His relationship to the uncanny works the same way. He begins with intention a mood to unsettle, a symbol to fracture. But the moment where the image actually tilts into something stranger? That arrives on its own. A glitch. A shadow. A texture behaving unexpectedly.

He doesn’t plan those moments. He recognizes them and follows them. That shift from director to collaborator, from controller to witness that’s where his work gets its power.

Here’s what keeps rattling around in my head after talking to Daniel: What if we’ve been thinking about creative control all wrong? What if the moments we lose control are exactly when the subconscious gets to speak? What if listening to what wants to emerge matters more than forcing everything to match our original vision?

Because we live in a culture obsessed with intention. With deliberate choices. With executing vision precisely. But Daniel’s showing something different: the best work often emerges when you plan the framework but allow the details to surprise you. That’s not chaos. That’s trust. Trust that the work knows something you don’t. That the image has its own intelligence. That your job isn’t always to control sometimes it’s to recognize and follow.

But looking at what Daniel’s built this entire visual language that feels both familiar and unsettling, beautiful and disturbing, controlled and wild I’m convinced he’s onto something essential.

Follow Daniel Andersson through the links below to see what happens when someone builds a practice on recognizing rather than planning the uncanny.