Watching Parents Be Happy Without Wealth Gives Children The Permission They’ll Need Later I David Vegt

👁 62 Views

At Arts to Hearts Project, we’ve noticed something about artists who build sustainable, meaningful practices: they rarely come from privilege. They come from watching a parent choose happiness over money. From small towns where success looked different. From homes where joy didn’t need wealth’s permission.

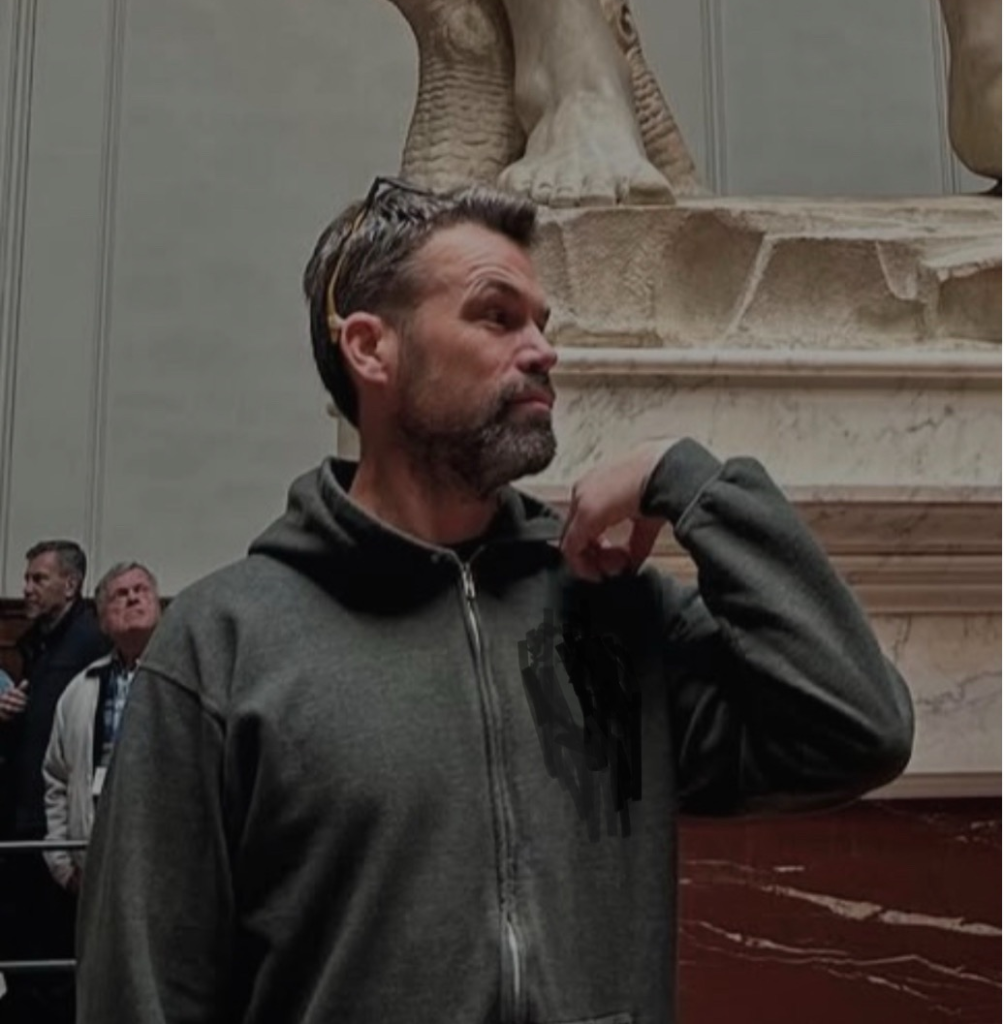

David Vegt is one of those artists. He’s a selected artist for our 101 Artbook: Landscape Edition, and when we first encountered his work, we wanted to know how someone develops that kind of presence on canvas. That ability to capture not just a face or a landscape, but the feeling of being seen by another human.

The answer took us somewhere unexpected: Vernon, British Columbia. A small town. A father who was a professional photographer, never rich, but genuinely happy doing what he loved. A mother who liked to draw and helped with school projects, clearly talented but never pursuing it professionally.

And here’s what stopped us: David said watching his father be happy without wealth gave him something most people never get. Permission. Not to make money first and then follow passion. But to follow the work itself and trust that everything else would either come or not come, because the world of art is fickle and taste changes and none of that is in your control anyway. That’s a radically different foundation than most professional artists have.

Most artists we talk to describe fighting for permission. Justifying their choice to family. Proving it’s viable. Defending it against practical questions. David didn’t have to do that. He watched his father live proof that you can be happy doing creative work in a small town without getting rich. That genuine happiness not performance, not success-despite-odds, but actual contentment, that’s what gave him the foundation to persist.

Because here’s what became clear as we dug into his story: his career wasn’t built on talent alone. It was built on persistence. Unwavering belief. The ability to keep putting one foot in front of the other even when the path was completely unclear.

He was discouraged at every turn. An elementary school teacher ripped up his drawing of hockey players and threw it in the garbage literally discarding what mattered to him. A high school art teacher who cared more about supplies than the students sitting in front of him. No formal training. No one telling him he had what it took. No external validation saying he should keep going. Just his father’s quiet example of happiness without wealth, his mother’s unspoken talent helping with school projects, and his own stubborn refusal to stop making things even when the world told him not to.

He’s now a sought-after portrait painter whose work emphasizes emotional depth as much as physical likeness. But when we asked how he captures the human soul in his paintings, he called it a trick question. He doesn’t think you can capture someone’s soul through physical appearance. What you can do if you take the time with sincerity is see who the person actually is, both physically and psychologically. And if you attempt to capture them in their most natural version, that aliveness comes through.

What drew us to select David for 101 Artbook: Landscape Edition is this: his story dismantles something we’re told constantly. That you need money to pursue art. That you need formal validation. That you need a clear path before you start. He had none of that. What he had was a father who showed him genuine happiness doesn’t require wealth, and the persistence to keep going when the path was completely unclear.

Fifteen years ago, something shifted for him. He realized he wasn’t an artist to make money. He was an artist to make paintings. The money would either come or not come, and that was outside his control. His confidence went up when he decided to paint no matter what. Not as a business person. As an artist. First and foremost.

That shift from trying to succeed to simply continuing regardless that’s what sustained him. And now, years into his practice, he’s watching his own evolution. Early work focused on representation. Later work brings more expression thicker paint, more layers, more chaos. Because he has the confidence now to work through problems that arise when you add more risk.

We wanted to understand how watching a parent choose happiness over wealth gives you permission decades later. How you sustain belief when teachers discourage you. What it takes to build a practice that lasts when the path is completely unclear.

Let’s get to know David through our conversation with him exploring his journey from small-town beginnings, the teachers who tore up his work, the father whose contentment without wealth became his foundation, and what he’s discovered about persistence, about choosing to make art regardless of money, and about the kind of permission that actually sustains a creative life.

Q1. Could you share your background and creative journey from growing up in Vernon, British Columbia to becoming a sought-after portrait painter?

When I was in elementary school, when I was supposed to be reading, I was always drawing my favourite hockey players. I had a grade 5 teacher who saw that I was drawing instead of reading and took my drawing and ripped it up and threw it in the garbage. Then in high school, I had an art teacher who cared more about art supplies than he did about his students. But my father was a professional photographer, and though we lived in a small town and he was never rich, I could tell he was really happy doing what he was doing. And my mother liked to draw and used to help me with my school projects and I could see that she was talented in drawing. The main thing I would say that got me to where I am today as a full-time painter is persistence and curiosity, and an unwavering belief that you can do what you want to do. I think it’s important to remember that no one can see into the future, when I decided to try and paint for a living, the path was very unclear, but if you keep putting one foot in front of the other, there is a much better chance of arriving at your destination.

Q2. Your portrait work emphasizes emotional depth as much as physical likeness how do you approach capturing the human soul, not just the face, in your oil paintings?

I think it’s a bit of a trick question, to say that you can capture someone’s soul through their physical appearance, I think it is a stretch. But if people seem to feel an aliveness that comes through my portraits, it is because I have taken the time with sincerity to see as best I can who the person is, both physically and psychologically, so that my attempt to capture them in what I think is the most natural version of themselves, comes through.

Q3. Birch panel painting has a very particular texture, and luminosity why did you choose this substrate, and how does it influence the final piece?

I like the stiffness in wooden substrates, I started on birch panel and now I’ve actually switched to aluminum panels as they are even smoother and I can make my own texture by adding gesso in a random pattern. I don’t like the bounce and movement of canvas. I think it’s just a matter of taste and is what I am used to now. I think it influences the final piece in that I am in total control of the texture and don’t have to rely on the tooth of the canvas.

Q4. Your workshops focus on classical fundamentals; how do you see traditional skill-building impacting contemporary artists’ minds and confidence today?

A friend of mine, Colleen Barry, just wrote an article about this in her substack called M.A.P. (modern age painting).

Alot of young artists are wanting to express themselves visually, and the institutions have failed to hold onto the aesthetic principles and fundamentals of the past.

There are some ateliers that are teaching hard skills but are not feeding the creative aspirations of this next generation, so we have this split between some schools just teaching hard skills and others trying to foster ideas and concepts without those hard skills. So, I’m seeing a disconnect and wanting to provide a place for people to work on both. I have just started an online platform called The Living Atelier, on the Skool platform, where I am teaching both the hard skills and challenging new painters to think about meaning and why they are painting in the first place.

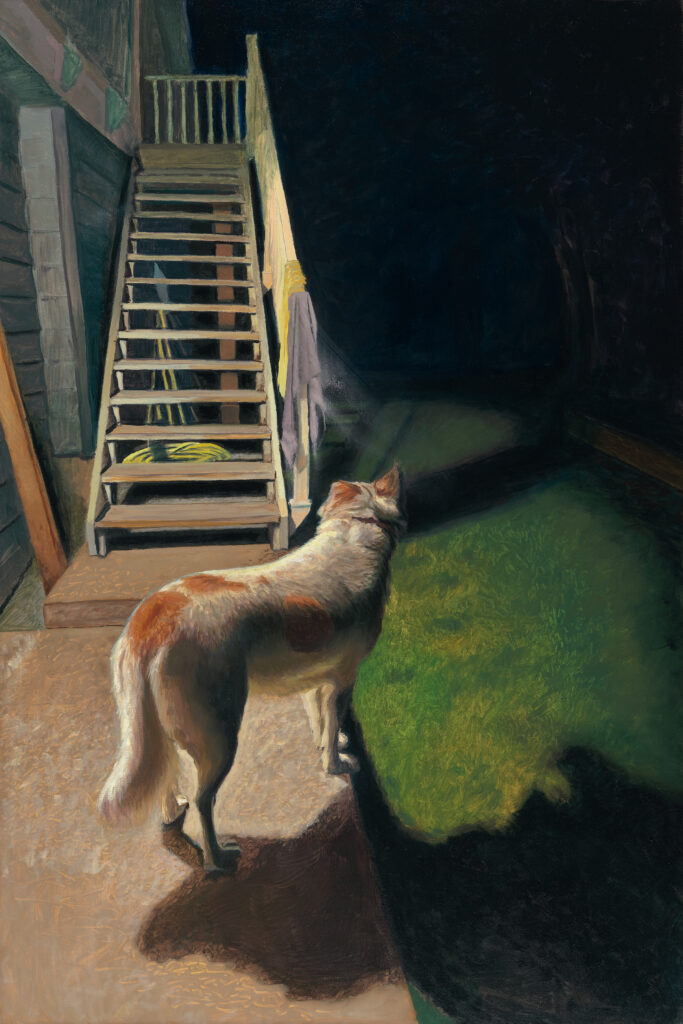

Q5. Could you describe a painting that surprised you, where the process led you somewhere you didn’t expect?

Usually, I like to have complete control over my painting process, but there are times when things happen and you don’t expect it, and you get lucky. It doesn’t happen often but when it does, it has the potential to add an entirely new level to the painting. I painted a figurative painting of my dog in my backyard, and there were towels hanging on the railing, and when I went to varnish the painting, some of the paint pulled off of the towels and made this sort of ghostly mark that trails into the darkness. Though this was a mistake, it totally added a kind of spiritual component that I wasn’t expecting in the painting, unintentionally it added to the uncanny feel of the painting.

Q6. Portraits are intimate by nature. How do you build trust and emotional connection with sitters, especially when working from photographs?

I think it’s more that the sitters trust my process and my ability to capture their likeness with sincerity by looking at work that I have already completed. I think artists build a trust with their sitters through their repertoire, their finished body of work that proves their ability to be consistent.

Q7. Can you recall a moment early in your career when your confidence as an artist fundamentally shifted and what brought that about?

I remember a time about 15 years ago when I realized that I wasn’t an artist to make money, I was an artist to make paintings and the money was going to either come or not come, because the world of art is fickle and taste changes drastically, and is out of your control. I think my confidence went up when I decided to paint no matter what, whether I was going to make money at it or not, because first and foremost I’m an artist, not a business person, not that there’s anything wrong with making money through your art.

Q8. Many classic artists you admire (like Manet and Rembrandt) balanced representation with expression; how do their influences manifest in your own work?

That’s a really good question, when I look at Rembrandt, for example, I can see that he went through his own evolution as a painter. I think similar to him I have been really interested and focused on representation in my earlier work, and expression is coming about more so in my later work because I have more experience and confidence in my ability to work through problems that arise by working with more paint and more chaos, thicker paint, more layers, it creates more expression.

Q9. How has your understanding of the “human spirit” as a painter deepened over the years of teaching, exhibiting, and creating?

I think my understanding of resilience and how people persevere through unbelievable trials has given me a more local focus, a greater affection for people in general, for all of their struggles and heartaches, and just trying to get through life with an outlook that is not entirely bleak. You can be a billionaire and completely miserable, you can be a starving refugee and have real joy, though the opposites are more likely. So much of life is about perspective and when I’ve been able to paint different people, I have seen how it can make them believe in themselves even more by seeing that someone has taken the time to really look at them, to create a representation of them that will inevitably outlast their own lifetime. It has a dual effect: it holds an image of them in time, and makes them realize that time holds on to no one in real life.

Q10. What advice would you give to emerging artists striving to develop a meaningful, enduring voice in representational art today?

The artists that survive are the artists that keep going. I have been friends with many fantastic artists over the years, and the ones that succeed are the ones that keep painting, keep making things despite their economic situation. The ones who succeed are the ones who are prepared when that lucky moment comes along when the right people in the right places find them, or they put themselves in the right places to be found. Instagram can be a blessing and a curse, spend more time painting than looking on Instagram. The practice will make the painter

Wrapping my conversation with David, I kept thinking about something he said almost casually: his father was never rich, but David could tell he was really happy doing what he was doing. Read that again. Not “he seemed happy.” Not “he tried to be happy.” He was happy. Genuinely. Without wealth. In a small town. Doing creative work.

And that observation, that moment when a child recognizes their parent’s genuine contentment that’s what gave David permission to build his entire life around painting. Not his talent. Not his training. Permission. Here’s what I realized talking to David: we’ve been asking the wrong question about artistic careers.

We ask: do you have talent? Do you have training? Do you have connections? Do you have a plan? We should be asking: do you have permission? Not permission from institutions. Not permission from the market. Permission from somewhere deeper. The kind that sustains you when a teacher rips up your work. When the path is completely unclear. When money isn’t coming. When every logical voice says stop.

David’s father gave him that without ever intending to. Just by being genuinely content doing creative work in a small town without getting rich. That example was louder than any teacher’s discouragement. More powerful than any formal validation. Because it was proof, not theory, not aspiration, but living proof that happiness doesn’t require wealth’s approval.

Most of us never see that proof. We see parents who sacrificed their dreams for stability. Who chose money over joy. Who warned us not to make their mistakes. And we internalize the message: creativity is a luxury you earn after you’re financially secure. Art is what you do when you can afford to.

David internalized the opposite. And fifteen years into his practice, when he realized he wasn’t an artist to make money but an artist to make work, that realization didn’t break him. It freed him. Because he’d already seen his father live that truth. The money comes or it doesn’t. The world of art is fickle. Taste changes. None of that matters if you’re doing the work itself.

That shift from seeking success to simply continuing—that’s what separates artists who sustain practices from artists who burn out. Because once you stop tying your work to external validation, you’re no longer at the mercy of a market that doesn’t care about you. You’re free to just work. To evolve. To take risks without fear dictating every choice.

What struck me most about David’s teaching philosophy is how it addresses something most art education ignores: you need both the how and the why. Technical mastery without creative purpose is empty. Creative passion without skill is unsustainable. Most schools give you one or the other. David’s giving both. Because he understands from experience—you can’t build a decades-long practice on technique alone. And you can’t build one on passion without the skills to execute.

But here’s what I keep coming back to: the permission question. Where does yours come from? Not your talent. Not your connections. Your permission to continue when the path is unclear. When teachers discourage you. When money isn’t coming. When success feels impossible. When every logical voice says this isn’t working.

Because here’s what David’s story reveals: talent is common. Opportunity is random. But permission real, deep, unshakeable permission to continue regardless—that’s rare. And it’s what actually sustains creative work over decades.

Sometimes it comes from watching a parent choose happiness over wealth. Sometimes it comes from hitting bottom and realizing you’re going to do this anyway. Sometimes it comes from understanding that the artists who survive aren’t the most talented—they’re the ones who keep going when nothing else makes sense.

And maybe that’s the real lesson: stop waiting for permission from institutions, markets, teachers, family. Stop waiting for the path to become clear. Stop waiting for success to validate the choice because the artists who survive aren’t the ones with the most talent. They’re the ones who stopped waiting for permission and gave it to themselves. So, Start with the only permission that matters: your own. The kind David got from watching his father be genuinely content. The kind that says: I’m doing this regardless. Not because I’ll definitely succeed. But because stopping isn’t an option.

Follow him through the links below to see work that carries decades of choosing to continue.

.