Perfection In Art Is Knowing When To Stop I Viktoria Skityba Grivel

👁 38 Views

At Arts to Hearts Project, we’ve always been drawn to artists who don’t stop. Artists who face obstacles that would make most people quit, and instead of quitting, they find a way through. A way around. A way to transform limitation into something that fuels them forward.

Those are the artists we believe deserve space in Best of the Art World. And that’s exactly why we reached out to Viktoria Skityba Grivel.

Viktoria is a Franco-Russian visual artist working primarily with oil painting, exploring realism and hyperrealism in ways that feel surprisingly tender for a style often associated with coldness and control. She’s based in France now, but her life has taken her across continents born in Dagestan, grew up in Moscow, moved to Switzerland for education, lived in Bratislava, spent time in Marrakech, before finally settling where she creates today. Each place left its mark. Each move shaped how she sees the world and what she chooses to paint.

Her work focuses on subjects that seem simple at first glance soft toys, dolls, everyday objects rendered with meticulous precision. But there’s something underneath the technical skill. Something that makes you stop and stare a little longer than you planned. An emotional weight that goes far beyond the surfaces she’s capturing.

When we first came across her paintings, we knew very little about her story. Just that her work felt different from most hyperrealism we’d seen. Warmer. More alive. Like she wasn’t just showing off what she could do with paint—she was showing us what it feels like to really see something. To look at it carefully, gratefully, like it might not be there tomorrow.

We reached out because the work moved us. Because it carried something we couldn’t quite name but could definitely feel.

And then we started researching her background to prepare for this interview. Started learning about her journey. And what we discovered explained everything about why her paintings feel the way they do.

Viktoria didn’t grow up dreaming of being an artist. She didn’t go to art school. She came to painting later in life, encouraged by her husband who works as an art collector and advisor. He saw something in her, introduced her to the art world, inspired her to pick up a brush and try. And she did. Started experimenting. Started discovering that making art felt right in a way nothing else had.

She was just beginning to find her footing when everything changed. In 2014, Viktoria was diagnosed with Multiple Sclerosis. And as part of that diagnosis, she temporarily lost her vision.

Let that sink in for a moment. An artist just learning to paint learning to really see the world the way painters have to see it suddenly couldn’t see at all.

We kept thinking about what that must have been like. The fear. The anger, probably. The devastating unfairness of finally finding something that matters and having your body betray you right at the beginning. Most people would have stopped there. Would have called it a sign. Would have let that be the end of the story. But when Viktoria’s vision came back, she didn’t walk away from painting. She ran toward it.

Because something fundamental had shifted. Seeing wasn’t automatic anymore. It wasn’t something to take for granted. It was fragile. Precious. A gift that could be taken away without warning. And painting stopped being a hobby or even just a new passion. It became essential. A way to reclaim what illness tried to steal. A way to prove—to herself, to the disease, to anyone watching—that she was still here. Still seeing. Still creating. Still refusing to let limitation define what was possible.

Every detail she renders now, every brushstroke placed with impossible precision, carries that awareness. That gratitude mixed with defiance. That understanding that nothing is guaranteed and everything worth seeing deserves to be painted as carefully as humanly possible.

That’s why her work feels different. Because she’s not painting to impress you. She’s painting because seeing is a miracle she doesn’t take for granted anymore.

Her subjects aren’t random either. Childhood toys painted with tenderness. Dolls that somehow communicate personality through the smallest details. Light captured in ways that feel almost impossible. Each one is a choice about what deserves that kind of sustained attention. What’s worth looking at so carefully that you can translate it into paint that breathes.

She grew up in the former USSR during a time of scarcity—limited electricity, limited resources, life built on community because you had no choice but to depend on each other. That experience gave her a deep awareness of fragility. Of how quickly comfort can disappear. Of how much warmth and gentleness matter when everything around you feels uncertain.

And now, working through illness, moving through countries, building a practice from scratch without formal training—all of that shows up in her work. Not as darkness or heaviness, but as intentional light. As conscious choice to create joy, tenderness, peace. Because she knows what it’s like when those things are absent. And she refuses to add more weight to a world that already carries plenty.

The more we learned about her path, the more questions we had. Not just about technique or process, but about resilience. About what it takes to keep going when your body makes creating harder. About how you maintain emotional clarity in work that demands such discipline. About what it means to paint when every act of seeing feels like borrowed time.

So, let’s hear from Viktoria herself. About what happened when sight became fragile. About how painting became resistance. About what it’s like to create hyperrealism when you know, viscerally, that nothing you’re looking at is guaranteed to stay in focus.

Q1. Can you share your background and the path that led you to your artistic practice from your earliest encounter with art through the personal experiences that shaped your voice?

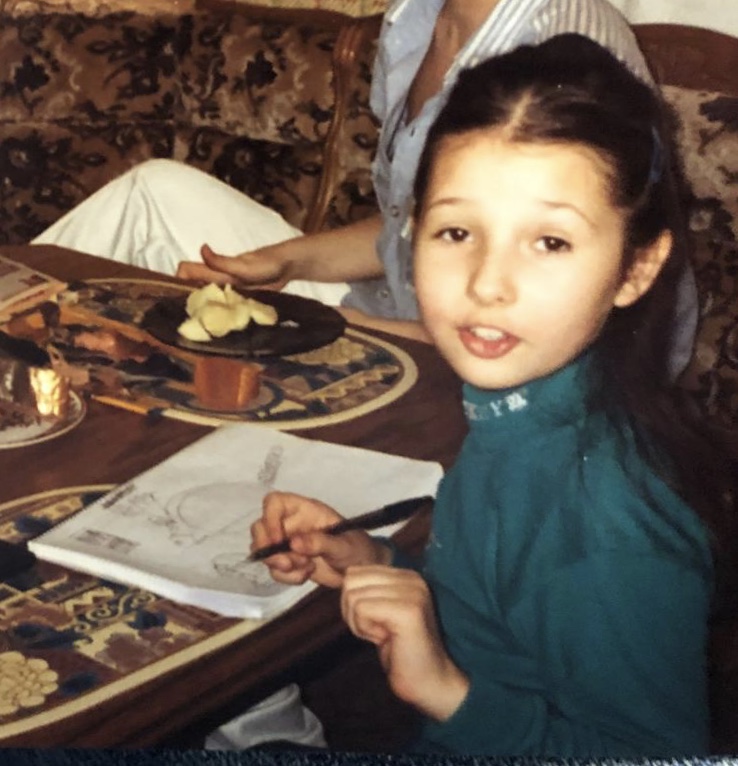

I am a Franco Russian visual artist working primarily with oil painting, exploring realism and hyperrealism to convey emotion, memory, and inner worlds beyond surface appearance. My earliest encounters with art were rooted in imagination and play, creating stories and emotional lives for objects like dolls and toys, a sensibility that still shapes my subjects today. My path to art was not conventional. I came to painting later in life, encouraged by my husband, an art collector and advisor, who introduced me to the art world and inspired me to begin creating. A pivotal moment came in 2014, when I was diagnosed with Multiple Sclerosis and temporarily lost my vision. This experience profoundly changed my relationship to seeing and to making art. Painting became essential, a way to reclaim vision, express resilience, and explore emotion with intensity and care. Today, my work reflects this journey, combining technical precision with tenderness, playfulness, and a deep emotional connection to the viewer.

Q2. How has living with Multiple Sclerosis influenced not only the content of your work but your philosophy toward making art and interpreting visual language?

Living with Multiple Sclerosis fundamentally changed my relationship to vision, time, and presence. Experiencing temporary vision loss made seeing feel fragile and precious, and this awareness deeply influences how I approach both content and process. I paint slowly and attentively, treating each detail as an act of care and resistance. Being independent and working as an artist has also helped me live better with the illness in many ways, it has been more powerful than therapy. Creating gives me autonomy, purpose, and emotional balance. It allows me to transform uncertainty into focus and vulnerability into strength.

Q3. In your early work you painted things that were “unreachable” to you due to life circumstances. How did that imaginative transformation turn into a core strategy for developing your style?

Painting what was unreachable became a way to overcome limitations imposed by life circumstances. Imagination allowed me to access worlds, objects, and emotions that were physically or emotionally distant, turning desire and absence into creative material rather than frustration. Over time, this approach became central to my style. I learned to use realism not just to represent reality, but to make imagined or idealized subjects feel tangible and present. Painting became a way of reclaiming control, transforming longing into precision, and fantasy into something intimate, almost touchable. This imaginative transformation continues to guide my work, allowing me to blur the line between reality and inner experience.

Q4. The Fluffy series emerged from childhood experiences with toys can you describe how that memory landscape evolved into a sustained artistic theme that now communicates universal nostalgia?

The Fluffy series grew out of childhood memories of toys as emotional companions rather than simple objects. As a child, they were sources of comfort, imagination, and projection, they absorbed feelings that couldn’t yet be articulated. Returning to these forms as an adult allowed me to reconnect with that inner emotional landscape in a conscious way. Over time, the series evolved beyond personal memory into a broader vision. The walls of fluffs now represent our world as a human community. Each toy becomes a metaphor for a different person, varied in shape, emotion, and color, yet all existing together in harmony, offering love, respect, and acceptance. In this way, the work proposes a new vision of childhood toys: not only nostalgic objects, but symbols of coexistence, empathy, and shared humanity.

Q5. Can you reflect on the pivotal moment when you felt you discovered your signature style, where technique, emotion, and theme aligned most powerfully?

That clarity emerged through the Fluffy series, where soft, familiar forms painted with precision created a strong contrast between technical control and emotional openness. After discovering my voice with Fluffy, I wanted to push it further by exploring new textures and surfaces. This led to the Barbie collection, where I moved from fur to skin and plastic, translating the same emotional language into a different material reality. Today, I am working with yet another texture , more liquid, reflective, and transparent. This exploration resulted in the Cocktail collection, where all these textures come together, allowing me to play with light, reflection, and sensuality while continuing to evolve my visual language.

Q6. Your use of accessories (oversized earrings, necklaces, fur) in the Barbie series acts almost like character cues, how do these elements inform the personality you assign to each subject?

In the Barbie series, accessories function as visual cues of identity rather than simple decoration. They are intentionally oversized in relation to the doll, just as Barbie accessories are larger than their real-life equivalents. When you look at a Barbie, everything, earrings, necklaces, shoes, is exaggerated, and I translate that logic directly into my paintings. I have collected more than 1,000 accessories, which allows me to construct a wide range of personalities within the series. Each combination of scale, texture, and color helps define character, attitude, and emotional presence. These elements let me explore how identity is built through details and surfaces. I am currently working on a commission in which a client asked for her portrait in the Barbie style, incorporating some of her own jewelry, extending this visual language into a personal and contemporary context.

Q7. Your Franco-Russian heritage figures in how you view creation and emotion. In what ways do these cultural currents surface in your choices of subjects, colors, and emotional resonance?

I was born in Russia, in the Dagestan region, grew up in Moscow, and later moved to Switzerland for my education. After that, I lived in Bratislava, Slovakia, and in Marrakech, Morocco, before eventually settling in France. All of these places and moments have shaped who I am today, both personally and artistically. I wouldn’t say my work is directly about my origins, but rather about my education through family, lived experience, and encounters with people. My visual language is built from observation, adaptation, and emotional exchange. That said, some places have influenced my work more strongly than others, certain environments, cultures, and energies have naturally invited deeper reflection, affecting my choice of colors, atmosphere, and emotional tone. My work is less a map of where I come from, and more a record of how I have lived and what I have felt along the way.

Q8. Your work often evokes gentleness, joy, and tenderness. How do you maintain that emotional clarity in the midst of the technical rigor required for photorealism?

I come from a generation in the former USSR where daily life was shaped by scarcity, limited electricity, limited resources, and a strong dependence on community. Growing up in that environment created a deep awareness of fragility, but also a lasting desire for warmth, gentleness, and shared humanity. Because of that, I consciously choose light, joy, and tenderness in my work. While photorealism requires discipline and technical rigor, I approach it as a meditative process rather than a struggle. I don’t use painting to reopen painful memories; instead, I use it to build a sense of peace. Creating images that feel soft, joyful, and emotionally clear allows me to focus on the present and to imagine a positive future, for myself and for those who engage with my work.

Q9. With social media building a broad audience for your studio and creative process, how has this visibility influenced the way you think about making work versus sharing it?

Social media has helped me build a wide and very direct relationship with my audience, offering a window into my studio and creative process. However, it hasn’t changed the way I make my work. Painting remains a private, focused space where I work slowly and intuitively, without thinking about visibility or performance. What social media has changed is how I share the work, not how I create it. It allows me to demystify the process, to show time, effort, and vulnerability behind photorealism, and to connect with people in a more human way. For me, the balance is important. The work must stay honest and personal in the studio, and only afterward does it enter the public space as something shared rather than produced for attention.

Q10. Are there moments in your journey when uncertainty or limitation unexpectedly redirected your practice in a meaningful way?

Yes. Uncertainty and limitation have often redirected my practice in meaningful ways. Experiences with illness and changing life circumstances forced me to slow down and rethink my relationship to vision, time, and attention. Rather than resisting these limits, I learned to work within them. They pushed me toward intimacy, softness, and clarity, shaping both my visual language and the emotional focus of my work.

Q11. Many artists speak about “letting go” of perfection, how do you navigate perfectionism in your process, especially with such detail-oriented work?

Have you ever changed your home decoration? Art is very similar. A piece is never truly finished. The more you look at it, the more you want to add, adjust, or change. With highly detailed work, there are moments when the process becomes difficult and you almost want to burn the piece. At that point, I step away. I let the work rest for a few days and return only when the right feeling comes back. There is also a moment when you have to let it go, even if you could continue working on it. For me, perfection is knowing when to stop, when the emotion is complete and the painting no longer needs me.

Q12. What kind of inner response do you wish your work to awaken in the viewer before they begin to analyse it intellectually?

Before any intellectual analysis, I would like viewers to truly look at the work and let themselves be inspired. The first response I hope for is emotional, a moment of attraction, curiosity, or recognition, before searching for meaning. I often hear that my paintings would be perfect for decorating a child’s room, but the message is not for children. The work speaks through childhood memories, but it addresses experiences and emotions that everyone has lived or carried into adulthood. That contrast is important to me. I believe understanding an artist’s vision helps clarify the message behind the work. Of course, everyone is free to form their own interpretation, but I always encourage viewers to first engage with the artist’s intention, o read, to look carefully, before imagining other versions of the story.

Q13. Looking back over your exhibitions since 2017 from Autour De L’eau to your recent solo shows what shifts do you see in your confidence, technique, and conceptual depth?

Looking back, it feels like the work was made by two different people. When I started painting in Switzerland, I had no real knowledge of art or technique. It began almost as a hobby during a difficult period of illness, something to fill the days and distract me from pain and the heavy effects of medication. I painted what was in front of me: boats, lakes, mountains. There was no clear intention or conceptual framework, just the need to do something. Everything shifted when I moved to Slovakia and began a new treatment that made me feel physically and mentally better. That change in well-being directly affected my work. This is when the Fluffy collection appeared. As my life became lighter, my art became brighter, more colorful, and more emotionally open. For me, the connection is direct. The better I feel in life, the more joy, clarity, and confidence naturally appear in my work.

Q14. What advice rooted in your personal challenges, artistic development, and resilience would you give to emerging artists striving to find their own voice and build a meaningful practice?

If you want to be an artist and truly live from your work, you have to be prepared! It is a daily fight. First, a fight with yourself: to create consistently, to structure your time, and to keep going even when doubt appears. Then comes the challenge of visibility and recognition, which also takes patience and resilience. It takes time, discipline, and a lot of effort, and no one succeeds alone. Support from other professionals in the art world is essential. My biggest mistake at the beginning was staying too isolated. My advice is to stay open, connect with other artists, share experiences, and build a community. Art may be personal, but a meaningful practice grows through exchange, support, and persistence.

Wrapping my conversation with Viktoria, I couldn’t stop thinking about one thing: what do you do when your body takes away the one thing your dream requires? Most of us would quit. Call it fate. Say it wasn’t meant to be. Move on to something safer, something our bodies won’t betray us for trying.

Viktoria didn’t do that. And honestly? That decision—that refusal to let illness write the ending that’s what makes her story matter more than her technical skill ever could. Because here’s the truth nobody wants to say out loud: talent doesn’t sustain you through the hardest parts. Passion doesn’t keep you going when your body makes creating painful. Skill doesn’t matter when the thing you depend on most becomes unreliable.

What sustains you is something else entirely. Something most people never find because they never have to look for it. Viktoria found it when she lost her vision. When the universe handed her the perfect excuse to stop painting forever. When everyone would have understood if she walked away. She didn’t walk away. She painted her way back.

And that choice that absolute refusal to let limitation define what’s possible that’s what you see in every brushstroke. Not just technical precision. Not just hyperrealism. But proof that losing something doesn’t mean it’s over. It just means the story changed.

Think about that for a second. She came to painting later in life. No formal training. No childhood dream. Just someone trying something new because her husband encouraged her. And right when she was starting to figure it out, her body said no.

Temporary vision loss for an artist learning to paint hyperrealism. It’s almost cosmically unfair. But here’s what I realized talking to her: maybe that’s exactly what gave her work its power. Because now she doesn’t take seeing for granted. Ever. Every time she looks at something really looks, the way painters have to—she’s aware it might not last. That vision is a gift, not a guarantee. That nothing you’re looking at is promised to stay in focus.

So, she paints like it matters. Like every detail is worth rendering with impossible care. Like the act of seeing clearly is itself a small miracle that deserves to be honoured. Most hyperrealist artists paint to show off. Look what I can do. Look how skilled I am. Look how perfectly I can render reality.

That’s not naivety. That’s strength. Because let’s be honest: it’s easy to create dark art when life is dark. It’s easy to paint suffering when you’re suffering. What’s hard what takes real courage is choosing to create beauty when your body is fighting you. Choosing gentleness when illness makes everything harder. Choosing joy when you have every reason to choose anger instead.

Viktoria chooses joy. Every single day. In every single painting. And that choice is more radical than any technical skill could ever be. Here’s what her story taught me, and what I hope it teaches you: Your limitations don’t disqualify you. They redirect you. Sometimes the thing that almost breaks you becomes the thing that makes your work matter. Sometimes losing what you thought you needed teaches you what actually sustains you. And maybe, just maybe the artists who create the most meaningful work aren’t the ones who had it easiest. They’re the ones who had every reason to quit and kept going anyway.

So if you’re reading this and something is making your dream harder than it should be if your body isn’t cooperating, if circumstances are fighting you, if the path isn’t clear remember Viktoria. Remember that she lost her vision and painted her way back. Remember that limitation became fuel instead of excuse.

And if something is trying to stop you right now don’t let it. Paint your way through. Create your way forward. Let limitation redirect you instead of defining you. Because if Viktoria can paint hyperrealism after losing her vision, you can do whatever you’re afraid you can’t do. The only question is: will you let difficulty write your ending, or will you paint your way to a different story?

Follow Viktoria Skityba Grivel through the links below to see work her work that proves talent matters less than resilience. That perfection matters less than presence. That the most powerful art comes not from having everything you need, but from creating despite lacking what you thought was essential.