Sometimes The Strangers You Meet For Three Hours Stay Longer Than People You’ve Known For Years I Katalina Brincos

👁 107 Views

At Arts to Hearts Project, we’ve learned that the best portraits aren’t painted from life. They’re painted from loss.

Katalina Brincos paints people she’ll never see again. And that limitation, that permanent distance between artist and subject is exactly what makes her work impossible to look away from.

She’s a selected artist for our International Artist Award and featured in The Great Book of Art Makers, but here’s what stopped us cold when we first saw her paintings: these aren’t portraits of people. They’re portraits of the feeling people left behind.

There’s a difference. And once you understand it, you can’t unsee it.

Katalina spent over a decade as a flight attendant, traveling to more than a hundred countries. Which means her entire artistic practice is built on something most painters would consider a nightmare: no model to reference, no way to verify accuracy, no second chance to get it right. Just memory. And memory, unlike a photograph, doesn’t care about facts. It cares about what hurt, what surprised you, what stayed lodged in your chest long after someone walked away.

Her artist statement says it plainly:

“I paint people I have met. What I am really painting is what stays”

Read that again. Not who stays. What stays.

Because here’s the truth she’s figured out: sometimes a stranger you talked to for three hours on a flight changes you more than people you’ve known your entire life. Sometimes a gesture a silence, the way someone held themselves, the energy they carried that fragment matters more than their name, their story, their entire biography.

And when you can’t go back, when you have no photo, no Instagram handle, no way to track them down what you paint isn’t their face. It’s the shape of the hole they left when they disappeared.

That’s what makes her work so unsettling in the best way. You look at her portraits and you recognize something. Not the person. The feeling. The weight of carrying someone forward even though they’re gone. The strange intimacy of brief encounters. The way some people rewire you in hours while others live in your life for years and leave nothing behind.

During the pandemic, when flights stopped and she couldn’t move, she started making jewelry handcrafted earrings called Brincos, inspired by places she was suddenly forbidden from visiting. The line got featured in Cosmopolitan Philippines and Preview Philippines. But that’s not the interesting part. The interesting part is what happened next: she realized her hands had been waiting to make things all along. And when she picked up a brush, painting didn’t feel like starting. It felt like returning.

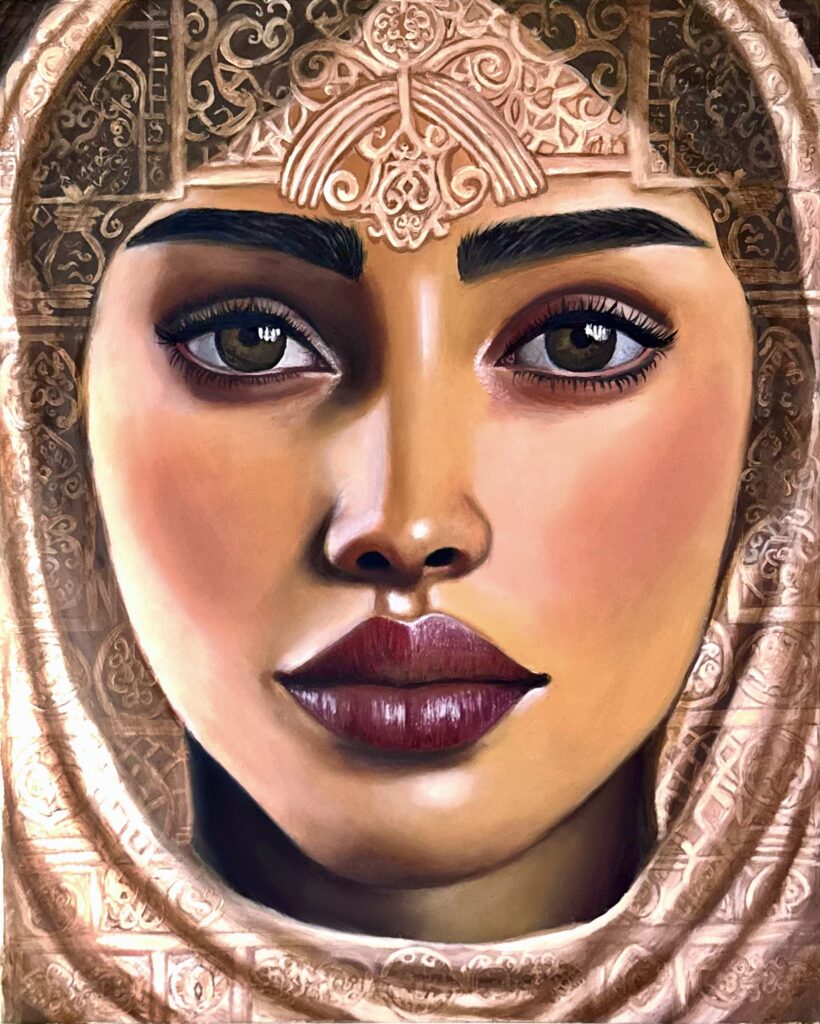

What makes her portraits even more distinct is this: she refuses to let people float in empty space. She weaves cultural patterns textiles, architecture, symbols into every composition, grounding each figure in the place where their story unfolded. She researches the roots of each motif, understands its cultural weight, then translates it through her own voice. The patterns aren’t decoration. They’re context. Proof that you can’t understand a person without understanding where they came from.

Women dominate her work. Not as muses. As infrastructure. Across every culture she moved through, she watched how women get reduced to appearance while simultaneously holding everything together memory, tradition, emotional labor, the invisible work that keeps societies functioning. Her paintings make that visible. Flip the frame. Say: these aren’t ornaments. These are the people carrying the weight.

Her work lives in a space most art avoids: the in-between. Home and departure. Presence and absence. Clarity and blur. Some faces in her paintings are sharp. Others dissolve at the edges echoing journeys that paused, identities still forming, people caught mid-transformation. That tension isn’t a flaw. It’s honesty. Because that’s how memory actually works. Some things crystallize. Others fade. And both matter.

We selected Katalina because her paintings ask a question most portrait artists ignore: what if you’re not supposed to paint who someone was? What if you’re supposed to paint what they did to you? What if the goal isn’t documentation, it’s archaeology? Digging through emotional residue to find what survived?

Her work doesn’t explain itself. It asks you to stay longer than comfortable. To sit with subjects you don’t recognize until recognition blooms from somewhere unexpected. To feel connection even when logic says you shouldn’t. In a world built for quick consumption, that demand feels almost aggressive.

But here’s what we realized: she’s not painting for the scroll. She’s painting for the people who’ve ever been haunted by a stranger. Who’ve carried a three-hour conversation for ten years. Who understand that sometimes what stays has nothing to do with duration and everything to do with depth.

Let’s get to know Katalina through our conversation with her.

Q1. Traveling across more than a hundred countries has shaped how you remember people and places. How does memory guide what stays in a face or pattern when you paint later on?

Memory doesn’t preserve everything. It edits. When I paint later on, I’m not trying to recreate a person or a place as it was. What stays with me are fragments shaped by emotion and energy. A look held too long, the weight of a silence, the way light rested on a wall, or how the air felt in a room. These impressions settle deeper and guide what remains in a face or pattern. Faces in my work are formed through emotional memory rather than strict observation. Some features become clearer because they carried presence, while others are softened through restraint. The same applies to patterns and environments. I don’t reproduce architecture or nature exactly. I translate how a place was felt into form, texture, and color. Painting becomes an act of remembering honestly. My work invites curiosity about place, memory, and lived presence. People flow in and out, places are entered and abandoned, patterns are learned and lost. Through painting, I decide what stays.

Q2. Portraiture became a way to hold on to people you encountered along the way. What draws you to certain individuals as subjects rather than others?

Meeting people has become second nature to me through my work as a flight attendant. Observing people trained my attention to subtle gestures, silences, and emotional cues. It helped me understand who they are beyond what is immediately visible. This draws me to the stories, energies, emotions, and quiet wisdom they carry. I see everyone as they are, beyond what they wear, their titles, or how they speak, and instead focus on what feels true beneath the surface. Even brief encounters can stay with us when they carry meaning. Those moments are what draw me to certain individuals and lead me to paint them later on. Through my work, I ask for the viewers to feel that same presence, sensing not only the person, but also the culture and nature of the place they come from.

Q3. The Brincos earrings began during the pandemic and later led you back to painting. What did working with your hands during that period teach you before returning to canvas?

The pandemic taught many of us to slow down and be present, creating space for things we had been carrying quietly for a long time. Working on Brincos was deeply hands-on and repetitive, and it reminded me how natural making had always been for me. Spending long hours shaping and assembling each piece allowed me to work without overthinking. When I returned to painting, I brought that same ease and focus with me. My hands already knew what to do, and painting felt less like a return and more like a continuation. Through Brincos, I found that fire again. It had been there all along, waiting, and it eventually led me back to the canvas with a renewed sense of presence.

Q4. Patterns linked to cultural roots often appear behind your figures. How do you decide which motifs belong with a particular person?

Often, a motif naturally reminds me of a person and the story they carry. It’s connected to the culture, environment, and atmosphere of the place where I met them or where their story unfolded. I then research the roots of the motif to understand its cultural context, before translating it through my own artistic voice. The pattern becomes an extension of the figure, grounding the person in place, memory, and cultural context.

Q5. Women appear in your work as carriers of cultural memory. What first led you to see women as central keepers of these stories across cultures?

Women became central in my work not through study, but through lived experience. Across cultures, I’ve seen how women are often overlooked, reduced to being seen as beautiful, decorative, or secondary. Yet beneath that surface, they are the ones carrying memory, tradition, and emotional labor. Women hold stories through gestures, rituals, and daily acts that often go unnoticed. They preserve culture in how they care, how they adapt, and how they endure. Even when their roles are quiet, their influence is lasting. This truth stayed with me as I moved between places and cultures. Painting women is my way of shifting that gaze. I work beyond appearance, toward what women carry. Through my work, I honor women not as ornaments, but as keepers of cultural memory, strength, and continuity.

Q6. Mentorships in Paris and recognition through international exhibitions have shaped your practice. How did these experiences shift the way you think about your work today?

For over a decade, travel defined my world. For a long time, I didn’t realize how much I had to share, or how to express it in my own way. Like learning to define colors as a child, my understanding of my work began simply and gradually became more precise. Mentorships, especially in Paris, helped me find that language. They taught me to slow down, question my choices, and understand why certain elements belong. International exhibitions then showed me how personal experiences can resonate across cultures, allowing me to connect with others and see the impact of my work. I was also able to meet fellow artists who inspired me in ways I didn’t know I needed. These experiences reshaped my practice. I create with greater intention, trusting the voice I’ve developed and embracing art as a continuous process of learning and growth, a challenge I choose to carry forward.

As I wrapped my conversation with Katalina, I kept thinking about something we don’t talk about enough in art: the difference between documentation and distillation.

Documentation captures what happened. Distillation captures what mattered. And Katalina’s entire practice exists in that second category, she’s not recording faces, she’s holding onto the emotional residue they left behind.

That’s a fundamentally different relationship to portraiture. Most artists treat the subject as the endpoint. Katalina treats the subject as the starting point. What she’s really painting is the space between encounter and memory, between seeing someone and carrying them forward, between knowing a face and understanding what it made you feel.

Her background as a flight attendant isn’t incidental to this, it’s foundational. She’s spent a decade in the business of brief intersections. People passing through. Strangers in transit. Encounters those last hours, not years. And here’s what that taught her: duration is a terrible measure of significance. Some three-hour conversations rewire you. Some decade-long relationships leave nothing behind.

Her work validates that truth in a culture obsessed with longevity. We measure relationships by how long they lasted, as if time equals depth. Katalina’s paintings argue otherwise. They say: what stays isn’t determined by duration. It’s determined by resonance.

The cultural patterns she weaves into her portraits do something quietly radical too. They refuse to let a person exist in isolation. They insist that identity is always contextual shaped by place, by heritage, by the systems and symbols surrounding us. By grounding each figure in cultural motifs, she’s saying: you can’t understand a person without understanding where they come from. And more importantly: you can’t honour a person without honouring that context.

Her focus on women as memory-keepers cuts through something we pretend isn’t true: that women’s labor emotional, cultural, relational is what holds societies together, even as it goes unrecognized. She’s not romanticizing that. She’s making it visible. Shifting the frame from ornament to infrastructure.

What strikes me most is her understanding that memory is an active process, not a passive one. When she paints someone from memory rather than from photographs, she’s acknowledging that forgetting is part of remembering. That what drops away matters as much as what stays. That clarity and blur aren’t opposites they’re collaborators in the act of holding onto what counts.

The pandemic revealed something too: sometimes you need to be forced into stillness before you realize what’s been waiting. Her jewelry-making wasn’t a detour. It was her hands remembering what they’d always known. And when she returned to painting, it wasn’t starting over. It was continuing.

Here’s what her work offers that most portrait art doesn’t: permission to value the fleeting. To honor the brief. To recognize that some strangers change you more than some family members. To admit that what you carry forward isn’t always what you chose to carry—it’s what chose to stay.

Follow Katalina Brincos through the links below to see how she turns three-hour encounters into lifelong impressions and proves that sometimes the people who stay the longest are the ones who were barely there at all.