5 Most Breathtaking Claude Monet Landscapes You Must See

👁 186 Views

Light has a way of sneaking up on you, spilling over a pond, glinting off leaves, or catching on a passing cloud. Claude Monet understood this better than anyone. He didn’t just paint what he saw, he painted what light itself felt like. Every brushstroke is like a tiny heartbeat, capturing a fleeting moment that could vanish the next second.

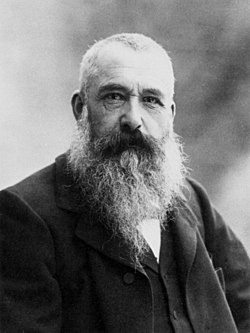

Monet was born in Paris in 1840, but his heart belonged to nature. He became the driving force behind Impressionism, a movement that shook up the art world because it refused to play by the old rules. Instead of rigid, lifelike representation, Monet focused on moments, moods, and the magic of everyday life. That was radical in a time when paintings were supposed to be grand, formal, and serious.

What makes Monet’s landscapes unforgettable is that they feel alive. A river isn’t just a river, a garden isn’t just a garden, everything shimmers with movement, light, and color. The way he captured morning mist, dappled sunlight, or the glow of sunset feels like nature is whispering straight to your eyes. You can almost hear the wind rustling or the water lapping.

People celebrated Monet not just for his technique but for the way he transformed the ordinary into the extraordinary. A field of hay, a row of poplars, a quiet pond, he could make all of it feel monumental without ever forcing drama. His work teaches you to notice the little things: how sunlight bends, how shadows stretch, how color shifts from one corner to another.

Monet’s genius was in showing the world how it feels rather than how it looks. Every painting carries rhythm, emotion, and a story of a particular moment in time. Whether it’s the shimmer of water lilies or the soft haze of early morning fog, you can sense the air, the weather, and the fleeting beauty that so often goes unnoticed in everyday life.

In this article, we’ll explore five of Monet’s landscapes that remain breathtaking today. Each one is a small portal into his way of seeing, reminding us why he is considered one of the greatest painters in history. By the end, you’ll understand why Monet’s work still inspires awe and why his landscapes are worth studying, lingering over, and returning to again and again.

Impression, Sunrise (1872)

This painting feels like waking at dawn and seeing the world exhale. Monet stood in the port of Le Havre and captured the way fog, water and light tangled at sunrise. The scene is minimal but electric: small boats, the hazy outline of cranes and masts, shimmering water and that glowing orange sun. It is as if Monet whispered “look” rather than shouted “behold.”

What is remarkable here is how Monet trusted the viewer. He used loose brushwork, almost sketch‑like, yet it isn’t unfinished, it’s freed. The grey mist and the orange sun play off each other in value so subtle you might miss it. When purchasers or critics first saw it they noted its unconventional style, soft forms, quick strokes, but Monet was doing something radical: capturing a feeling of light.

That orange sun is not blazing in traditional contrast; it almost dissolves into the sky. And yet it commands your gaze. The boats hardly exist as detail, they are silhouettes. The water echoes the sky. From a distance it reads like a memory. Up close the brushwork hums. It asks you to pause and feel the air, the mist, the moment.

Monet titled it “Impression” on purpose, he said the view couldn’t really pass for a typical, detailed depiction. So he offered his impression. That choice of word, once derisive, became the banner for a whole movement. The painting gave its name to Impressionism.

For you as a creative person studying landscapes this work is a masterclass. It shows that you don’t need every detail to be defined. You can suggest, you can imply, you can let atmosphere carry meaning. Monet teaches you to paint light, not only objects.

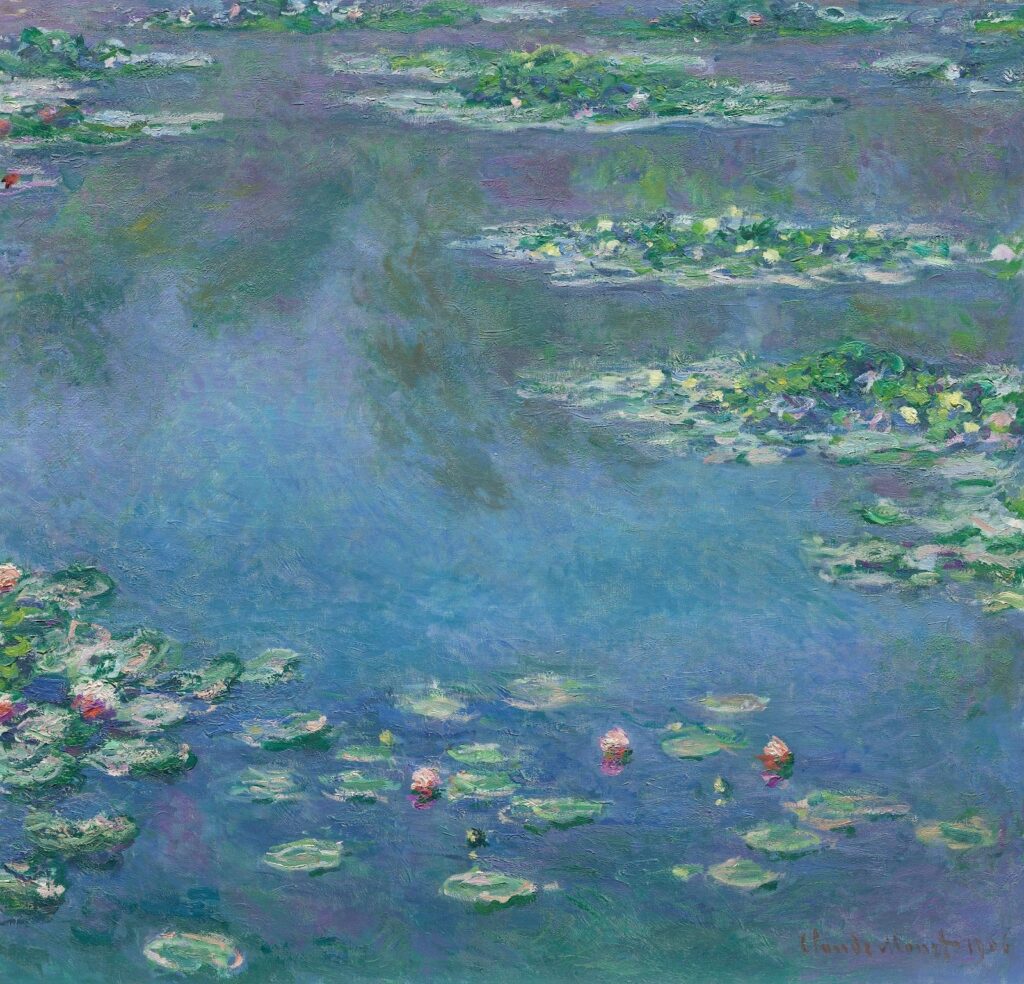

Water Lilies (Nymphéas) (ca. 1906)

This is the painting where Monet invites you into his garden at Giverny and then lets you wander, almost float. The surface of the pond becomes a mirror, the lilies hover, the air above the water is alive with reflection and ripple. There’s no distant horizon, no solid ground, it’s immersive.

What makes this piece breathtaking is how Monet dissolves boundaries. Water becomes sky, lilies become brushmarks, reflection becomes abstraction. The colours shift, the forms melt. It feels like you are inside the moment rather than outside looking in. That act of immersion is radical.

When you study the brushwork you notice layers of subtle colour: greens blues pinks purples, broken with whites. The light is not simply shining, it is vibrating. It moves. Monet shows that landscapes can be meditative, they can be still yet alive, silent yet insistent.

This work also speaks of Monet’s maturity. He had painted for decades by this time. He had refined his technique. He had learned to trust his senses. So this pond, simple as it may seem, becomes a vast field of inquiry into colour, light and time.

If you are writing or creating about landscapes this painting is a reminder: sometimes the subject can be small, quiet, intimate, and the meaning vast. You can turn a backyard, a garden, a pond into something universal. That is what Monet did.

Houses of Parliament, Sunset (1903)

Here Monet moved beyond gardens and fields and took on the city, the riverside, the fog‑laden Thames. Architecture and landscape, industry and nature, he merged them. The silhouette of the Houses of Parliament floats in the haze, the sky glows, the water reflects. What a daring choice.

The mastery here is subtle: the building is present yet dissolving into light. The towers anchor, but they are not the star, the light is. Fog, smoke, water, sky, they all converge. Monet shows how nature wraps itself around even the man‑made. It reminds us that landscapes include everything.

When you look closely you see the colour experiments: violets, greens, mauves drifting into pinks and oranges. The reflection is not a mere mirror but an extension. The horizon is low, the sky and water dominate. It feels like standing on the riverbank at dusk, the air heavy, the light fading, the structure looming yet soft.

For artists this painting teaches that the everyday can be mystical. A parliament building might seem cold or formal, but in Monet’s hand it becomes soaked in atmosphere, meaning and emotion. He stripped away the expected detail and let feel speak louder than form.

If you study it you’ll realise the light is the subject. The towers are props. The water and sky do most of the heavy lifting. That is a powerful lesson for anyone working in landscape: what you choose to emphasise changes everything.

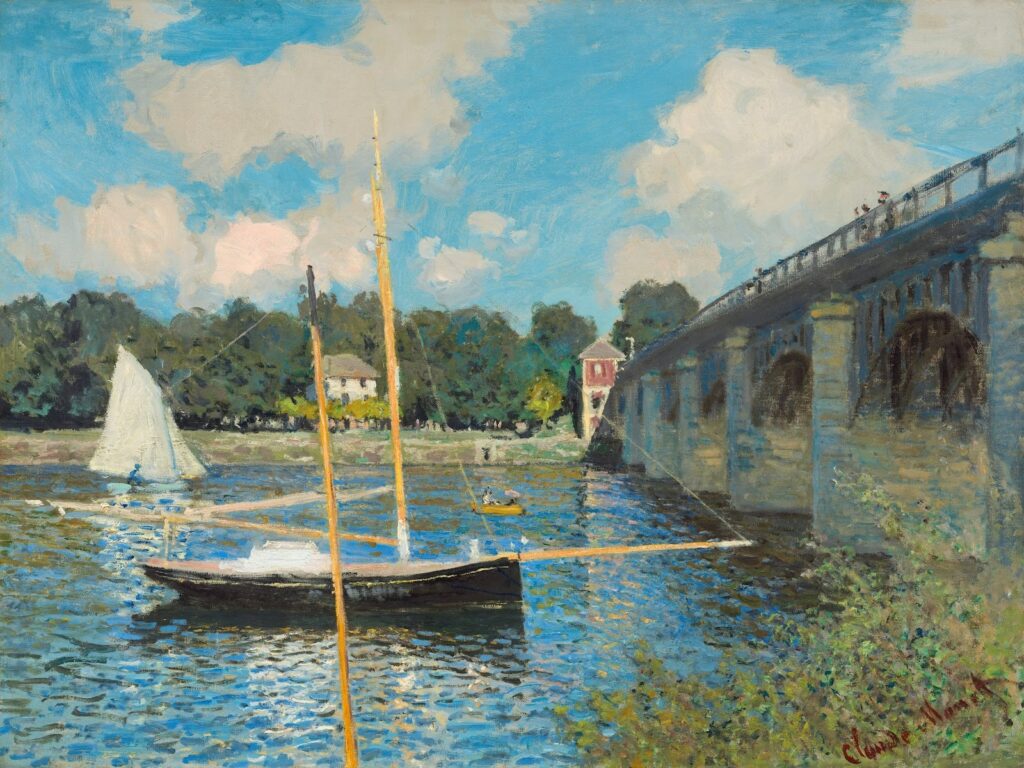

The Bridge at Argenteuil (1874)

Picture a shady afternoon by the Seine at Argenteuil: a bridge, boats, water, sky. Monet loved this place and painted it again and again. Here he gives us a scene that seems casual, everyday, but rendered with such intention and feeling that you notice how extraordinary the ordinary really is.

The brush marks are free, the palette bright yet harmonious. The water sparkles as if catching resin from the sun. The bridge spans, but it does not dominate, it connects. And the willow trees lean in, the boats drift. You feel calm, you feel the river breathing.

Monet in this work reminds us that landscapes don’t need grandeur to move us. This is not a mountain range or a sweeping vista, it’s domestic, accessible, human. And yet it contains all the elements: light, colour, form, reflection, movement. You can almost hear the paddle dip, the breeze rustle the leaves.

For someone studying art or writing about landscape this painting is valuable because it teaches composition not by spectacle but by subtle arrangement. The bridge divides space, the water reflects, the sky loosens up. The scene is balanced yet loose. That is Monet’s hallmark.

And also, Monet shows that being present matters: he painted en plein air, he painted the moment. Argenteuil was near Paris, he didn’t need to climb a mountain to find inspiration. He found it in his backyard, and so can you.

The Valley of the Creuse, Sunset (1889)

Here Monet takes you off the beaten path into a quiet French valley at the end of day. The sun is dipping; the colours turn warm; the valley expands. The scene holds peace and grandeur in equal measure. This piece might be less known than some, but it carries deep power.

Observe how Monet handles dusk: the light is waning, the shadows stretch, the palette turns richer. The water and rock and sky seem to merge. Rather than focus on detail he leans into mood. The result is a painting that fades into memory even as you study it.

This is a lesson for creators: you don’t need brightness, clarity and daylight to dominate a scene. Twilight works. Silence speaks. The valley here feels both timeless and transient, a place suspended between day and night. Monet gives us that threshold moment.

For someone writing about landscapes you might reflect on what tone you set: morning bursting with life or evening melting into calm? Monet shows us both and invites the latter, an hour where sensation and reflection merge. In this valley you feel the air shift, you feel the day closing.

And you learn too that landscape is not only what you see but how you feel. The Creuse Valley isn’t dramatic; it doesn’t need to be. Its beauty lies in its quiet unfolding, in the subtle tilt of the light, in colours soft yet resonant. That is Monet’s skill.