How Elizabeth Captures Human Strength to Her Photography

Elizabeth Pimentel is a documentary photographer from the Dominican Republic. In this interview she shares her journey in photography and how it connects with her background as an economist and philosopher. She talks about the powerful stories behind her photos, which focus on human vulnerability, strength, and the everyday acts of care that often go unnoticed. Elizabeth highlights the importance of jobs like raising children and nursing, which are crucial but often undervalued. Her work reflects the idea that personal experiences are deeply connected to broader social and political issues.

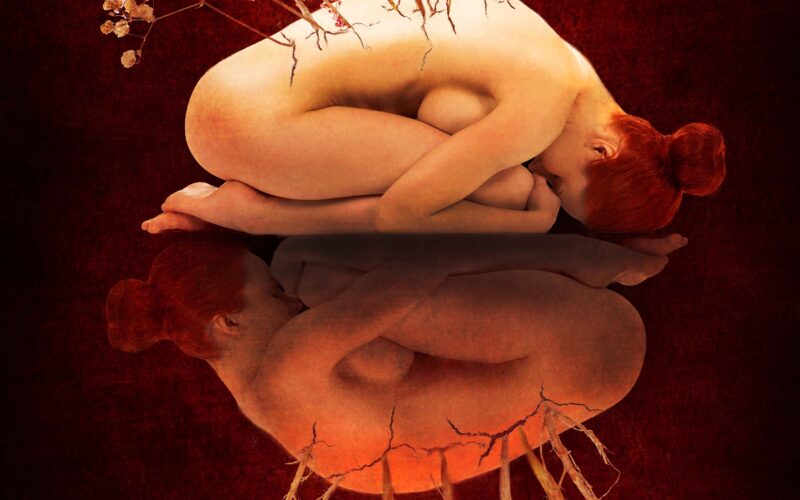

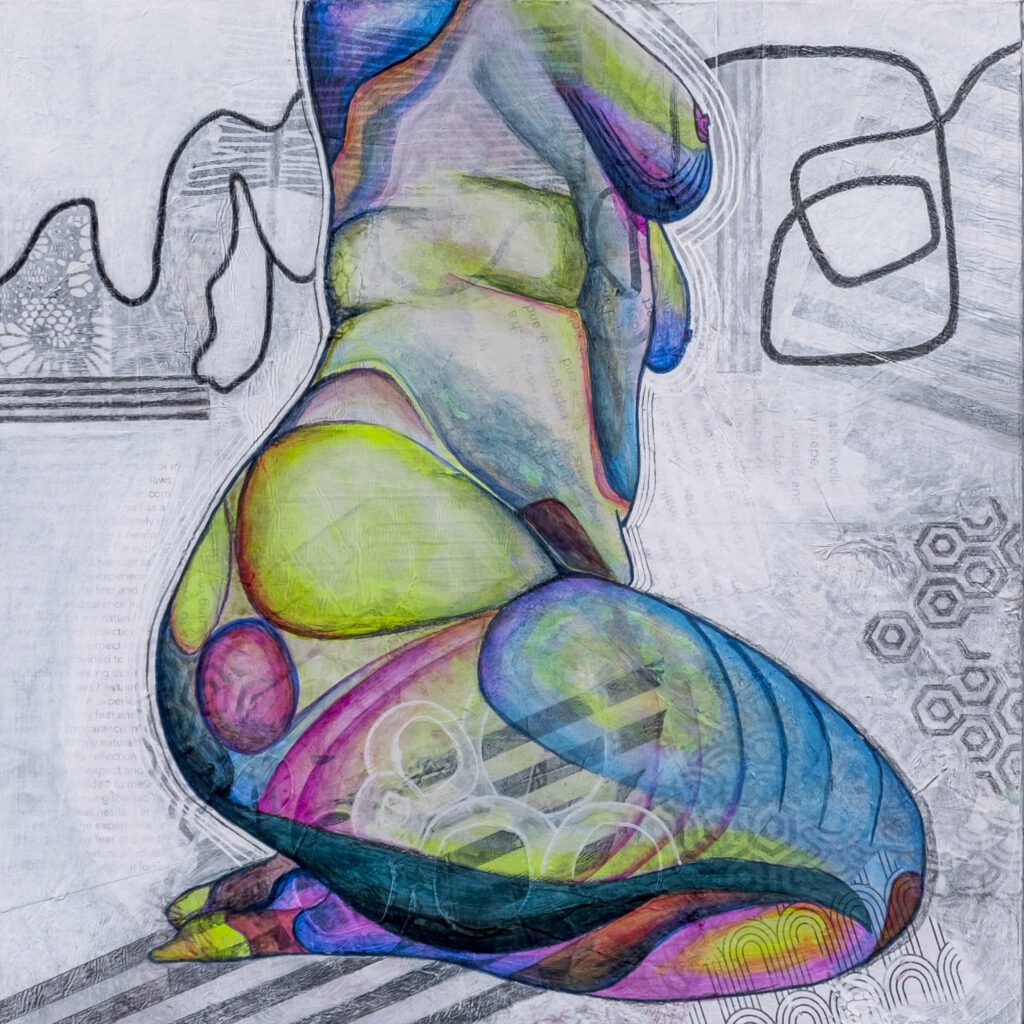

Elizabeth is a documentary photographer from the Dominican Republic who also works as an economist (BA, MPA, MSc) focusing on policy issues concerning human development and material and physical security. She mentioned that she turned to philosophy (PhD) to explore what fuels the underbelly of human intelligence and disposition. Her most important photographic subject is the person, emphasizing that we have such vulnerable and brief lives. According to her, how we live, our choices, and how we act are urgent matters, as there is much that would disassociate us from others if we allow it. She likes to capture moments of desperate optimism and tempered resilience, which give substance to otherwise dispassionate considerations of what it might mean to be in a world where what is hoped for has been radically altered by absurd yet entrenched notions of how we are expected to be. Her photographic practice is inclined toward the things we hold in common: our susceptibility for wonder, an innate curiosity about the planet and all things in it, a desire for some measure of immortality, and more humbly, a longing for being seen as we go about in the world.

Her latest projects give visibility to the work of social reproduction—whether in raising children, in social care, or in the nursing profession—as essential to human wellbeing. The works presented are inspired by social protest movements, of people becoming memory through political acts of solidarity and amity that give material presence to the work of care and social reproduction. She described this as a lifetime of labor that disappears with each passing moment and that few get to see. This work is often qualified as ‘free,’ or as low-wage, low-skilled labor, and does not feature as economically productive within national accounts of the measure of the market value of all goods and services, even though it is indispensable to the running of the economy.

1. Elizabeth, your photos beautifully capture human vulnerability and resilience. Can you tell us about a moment or story that inspired one of your pictures?

Certainly the post-pandemic years have seen children come out to protest with their parents and carere. It is such a joy to witness this next generation being socially conscious and politically active, without dogma or agenda. Life is happening during the actual protest, parents changing nappies, holding an impromptu picnic to keep spirits up, breastfeeding. Life can be uncertain and unpredictable, but capturing those small acts of humanity gives me hope.

When I’m out photographing it’s always that look or gesture in someone that speaks so much to our shared humanity and it’s so familiar, so embedded in who we are and who we try to become.

Elizabeth Pimentel

2. Your recent projects highlight the importance of jobs like raising children, social care, and nursing. What inspired you to focus on these areas, and what do you hope people take away from your work?

I trained as an economist and spent over 20 years working in policy in the area of human development which means critically going over national budgets and policy decisions and working out how they affect people in terms of stated goals. It’s amazing to me why care and labour in the home and community are not factored into socio-economic planning – a dearth of quality centres for early years education and nurseries, apathetic provisions for parents returning to work, little support within working environments for parents. There is actually a monetary value to this lost labour and it hovers close to £700 billion a year that’s lost in the economy and yet this work is foundational. We do it everyday, caring for our children and our elders, we nurture the past and nourish the future..

3. Your photography often shows ‘desperate optimism.’ How do you find and capture these moments in your subjects, and why do they matter to you?

The energy of a crowd united in purpose is something else. People decide to get out there and engage and make their voices heard, and they take strength in each other. I talk to a lot of people because I’m curious about why they’re there and what they hope will change, they hope for change but they’re not really sure it will happen because for a long time – first with so-called austerity, and the health crises, and now the cost of living emergency – things seem to be worse. There is no outward confirmation, no material outcome that all this effort is going somewhere but they do not give up. And it’s not just that they march and write letters to their Member of Parliament, but they’ll form community groups and help each other out while they wait and hope for universal change..

4. The slogan ‘the personal is political’ from 1969 is a big part of your work. How do you see this idea playing out today, and how does it influence your photography?

I think at times we – as just one person – may see ourselves too far removed from politics and the world of decision-making, but everything is politicised. Think about it. Women and carers who are not engaged in the so-called economy are deemed statistically as ‘economically inactive’. That’s unbelievable, and in fact it fills me with a quiet rage. It’s likely to be the same rage that drove feminists from the suffragette movements until today to highlight just how absurd it is the world is fabricated in a certain way that excludes any fundamental aspect of being human, that could be identity, a right to opportunity and expression, of civic engagement and recognition. When I’m out photographing it’s always that look or gesture in someone that speaks so much to our shared humanity and it’s so familiar, so embedded in who we are and who we try to become.

My photographic practice is inclined towards the things we hold in common: our susceptibility for wonder; an innate curiosity of the planet and all things in it; a desire for some measure of immortality, and more humbly, a longing for being seen as we go about in the world.

Elizabeth Pimentel

5. What advice would you give to new photographers who want to capture profound human experiences in their work?

Get to know your subject matter, what is driving that urge to capture that image you seek, what is the context. For myself, I do not believe one can be an unbiased, objective photographer, there is the desire and a duty of course to present the world as it is being shown to us, but I find it difficult to be a dispassionate chronicler of the times. I want to know why I’m there photographing: why do I see what I see?

Elizabeth’s photography gives us a deep look into the human experience, highlighting the importance of care work and the strength of community. She captures the beauty in everyday acts that often go unnoticed, reminding us how personal experiences are connected to larger social issues. Elizabeth’s work shows how art can shine a light on what it means to be human and the power of small acts of kindness and solidarity. To learn more about Elizabeth, click the following links to visit her profile.