Working in two locations taught her that home isn’t tied to one place I Trudy Rice

👁 28 Views

After seven volumes of our Studio Visit Book series, we’ve walked into just about every kind of creative space you can think of. Rooms flooded with natural light. Cramped corners carved out of bedrooms. Garages that still carry the faint smell of motor oil. Kitchen tables that get cleared for dinner every night. And we’ve learned something pretty clear by now: there’s no such thing as a perfect studio. The right studio is just the one that works for you, even if it doesn’t make sense to anyone else.

For Volume 7, we chose “Home” as our theme and asked artists what that word really means to them. Among the many artists we selected, Trudy Rice stood out because she’s literally living this theme. She doesn’t have one studio. She has two. One in the city, one on a farm. And both feel like home to her.

Most artists are trying to protect one studio space and stick to a routine. Trudy’s doing something totally different. She moves back and forth between two completely different places and that’s just how she works. When we first heard about it, we thought: wait, how does that even work? Doesn’t it mess with your focus?

But before we hear from Trudy herself, let us tell you a bit about what makes her practice interesting. Every time she walks into either studio, the first thing she feels is like she’s coming home. Not because everything’s perfectly set up, but because both spaces already know her. Her unfinished work is there waiting. Prints are drying. She looks around, reconnects with what she left behind, and one piece always pulls her back in.

Trudy makes prints, and her main process needs UV light. She lives in Australia where the ozone layer is damaged. For most people, that’s a bad thing. For Trudy, it means she gets more UV light to work with. The thing that’s hurting the planet is actually helping her make art. It’s weird to think about, but it’s just part of how things work for her.

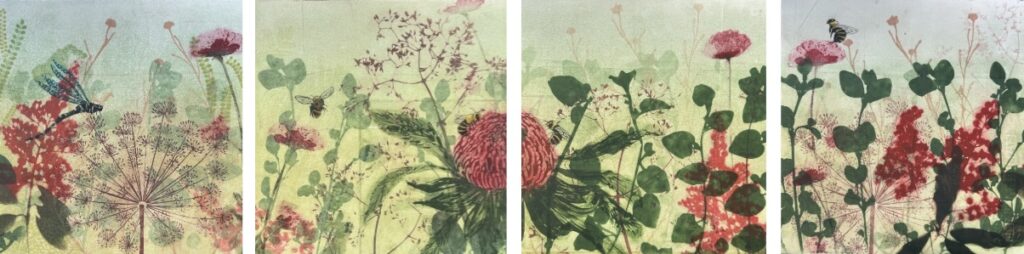

She uses tons of different materials drawings, solar plates, different printing techniques, a manual press. But to her, they’re not separate tools. They’re more like different ways of saying the same thing. She starts with a drawing. That turns into a plate. The first print shows her something she didn’t expect. Then she keeps building layers, each one responding to what came before.

Trudy also stepped away from art for years to raise her family. When she came back, her work was completely different. Before, she was exploring and experimenting. After, she knew what she wanted to do. Her studio became less about trying things out and more about building something that would last.

When Trudy walks through the Australian bush, she’s not looking where everyone else looks. Most people look up at the big views, the dramatic skies. Trudy looks down. At leaves on the ground. Seeds. Bugs. Small birds moving through the grass. Those little details get to her. Back in the studio, she works from memory and feeling. Her prints mix what she saw with how it made her feel.

She’s been drawing the same subjects for years wrens, banksias, little birds. They’re like old friends. What’s changed is how she draws them now. She’s gotten better, sure, but she’s also stopped worrying about making them perfect. She lets the drawings be loose. Emotional and totally Real.

No two prints ever come out the same, even using the same plate. The ink, the pressure, how you wipe it everything changes it just a little. That’s not a problem. That’s what makes each one unique.

Now let’s hear from Trudy about her two studios, Australia’s damaged ozone helping her work, why she looks down instead of up, and what home means when it’s more than one place.

Q1. Let’s begin with your studio as you experience it. When you step into your creative space, what do you notice first the arrangement of paper and plates, the presence of last-worked marks, or the light in the room & how does that shape the way you settle into work?

When I step into my studio, whether it’s my city space or on the farm, the first feeling is always a sense of belonging. It feels like I’m arriving home, somewhere that already knows me. I’m immediately drawn to my works in progress: the stacks of unfinished pieces and the heavy boards where completed works are drying. They tell me where I’ve been, and gently remind me where I’m going next. Because I move between two studios, there’s a moment of re-acquainting myself to where each work is up to. I sort through the unfinished pile, letting a particular piece quietly call me back in. Sometimes it’s a half-formed image that sparks a curiosity, other times it’s the inking slab, where I’m guided by the colour that feels most alive to me in that moment. This gentle process of noticing, remembering and responding is how I settle into work, slowly, intuitively, and in conversation with what’s already waiting for me.

Q2. Your printmaking involves multiple materials drawings, solar plates, inks, presses how do you keep these elements in conversation in your studio without the space feeling fragmented?

Although my practice draws on many materials such as drawing, solar plates, monotype, collograph, pochoir and the manual printing press, I don’t experience them as separate parts. They feel like different languages in the same conversation. I tend to work with one process at a time, but each stage is always informed by what came before and what is quietly forming ahead. When I enter the studio, the unfinished works guide me. I take time to see what is needed next, and that determines where I begin. When I’m developing a new body of work, I usually start with drawing. These drawings become solar plates, stencils, or collographs, and, through making and testing the plates, I begin to understand what the body of work wants to become. The first proofs often reveal more than I could have planned, showing me the next move. From there, the next layers are added, it may be monotype or pochoir, each one responding to what is already there. I think of the process as a gentle layering of conversations, each mark, colour or impression is listening to the last. This way, the studio never feels fragmented. It feels like a continuous unfolding where each material knows its place, and each stage quietly shapes the next.

Q3. Solar plate etching is a time-sensitive, sun-driven process that demands patience and rhythm. How does the tempo of light and weather affect your studio rhythms and decisions about when to print?

Living in Australia, I’m fortunate to have ample natural UV light for most of the year. Sadly in the south, the damaged ozone layer here means that solar plate etching can take place between late morning and mid-afternoon, pretty much most of the year round. Because of this, light rarely interrupts the flow of my practice. I have a light box for winter, when the days are shorter, and there is less UV. My manual press gives me the same freedom. I can print whenever I feel like it. This creates a studio rhythm that feels calm, intuitive and responsive.

Q4. You once put art aside and later returned to it with a renewed focus on printmaking and texture. Now reflecting on that pivot, how has your studio mindset transformed from those earlier years to today?

In my earlier years, my art was definitely more exploratory, and I was in that learning phase. Having family meant I had to prioritise and my art came second. But over time, my practice has now a much clearer sense of intention. Printmaking became central; it’s the language through which I express how I see the world. Today, my mindset is more focused and grounded. Being represented by Queenscliff Gallery has brought greater clarity and accountability. It has encouraged consistency, care, and steady growth in my studio life. I now see the studio as a place to build something lasting. A body of work that is more considered and shaped slowly over time.

Q5. When a composition begins to feel resolved on paper but not entirely complete to you, what do you look for, a shift in tone, a gesture repeating, a gap that feels unfinished?

Usually, it’s a gap that feels unfinished, maybe that gap is a certain colour, or that the composition isn’t sitting quite right.

Q6. Your subjects range from wrens and pardalotes to banksias and garden specimens. When drawing from memory and observation, how do you balance what you felt with what you see in your prints?

When I’m walking in the bush, I naturally look down at the small, quiet details. I’m less drawn to sweeping vistas and more to the intimate worlds underfoot: fallen leaves, seed pods, grasses, insects, and the soft movements of birds. These moments definitely provoke a feeling. When I return to the studio, I work from both memory and observation, allowing what I feel to guide the work’s atmosphere. In this way, the works on paper become a meeting place between emotion and observation.

Q7. Some of your compositions evoke quiet calm, others hum with life. In the studio, how do you sense when a work’s mood has shifted from serene to animated, and what do you do with that?

It’s interesting, I often begin with plants and foliage. I sometimes even try to resist “putting a bird on it.” But inevitably, the bush is not just a botanical world; it is a living, breathing ecosystem, and the animals that cohabit those spaces quietly insist on being present. I sense the shift when the work starts to feel like it needs something, when the stillness needs a sense of movement. That’s usually when a bird, an insect, or a small gesture of life enters the composition. It’s less a decision and more a listening, responding to what the work is quietly asking for.

Q8. Looking at earlier prints beside the ones you’re making now, what recurring gestures or motifs have stayed with you and what surprised you in how they evolved?

Banksias and blue wrens have stayed with me from very early on. They feel like old companions in my practice, familiar, grounding, and endlessly interesting. What has surprised me most is how my relationship with them has evolved. I feel I’ve become more confident and nuanced in drawing them, but also more willing to disrupt that drawing perfection. Like many artists, I’m always negotiating between accuracy and looseness, allowing the drawing to breathe, soften, and carry more emotion rather than simply striving for precision.

Q9. What advice would you give artists learning to honour material behaviour, particularly when prints or drawings resist what they initially intended?

Go with your materials. Experiment often. Let the materials speak. Printmaking is a constant reminder that no two impressions are ever the same. Even when using the same plate, the way the ink is mixed, the press pressure, and the rhythm of your wiping technique will all subtly affect the outcome. I’m still surprised, even after so many years, how a hand-pulled print can reveal something unexpected. That variation is not a flaw. It is the artist’s mark. It’s where the work becomes alive, and where the conversation between intention and material truly begins.

As we wrapped our conversation with Trudy, something shifted in how we were thinking about creative space and what it actually needs.

Most of us believe that discipline comes from consistency. One studio. One routine. One set of conditions we can control. We think that’s how you build something serious, how you avoid getting scattered. But Trudy’s been moving between two completely different studios for years city and farm, different setups, different rhythms and what she’s built isn’t scattered at all. It’s remarkably grounded.

That challenges a lot. Maybe consistency isn’t about doing the same thing in the same place every time. Maybe it’s about showing up with presence wherever you are. Maybe switching locations doesn’t break focus it actually keeps you awake to the work instead of just going through the motions.

Trudy’s situation also got us thinking about working conditions. She needs UV light for her prints. She lives in Australia where the ozone layer is damaged, which means more UV light. The thing hurting the planet is helping her work. That’s uncomfortable. She doesn’t romanticize it or pretend it’s simple. But she also doesn’t sit around wishing things were different. She just works with what’s there.

And honestly, that feels like a bigger lesson. We spend so much time waiting for the right circumstances. The right space. The right amount of time. The perfect conditions. But work doesn’t happen when everything’s perfect. It happens in whatever conditions we’ve got. The question isn’t whether those conditions are ideal—it’s whether we’re willing to figure out how to work anyway.

Trudy also walked away from art for years. Family came first. When she came back, her work wasn’t weaker. It was different. More focused. More intentional. More clear about what it was building. The time away didn’t erase anything. It gave her perspective.

We often think of time away as lost time. Like it sets us back or weakens what we’ve built. But Trudy’s experience says otherwise. Sometimes stepping away is exactly what lets you come back knowing what matters.

And then there’s home. Trudy doesn’t have one studio that feels like home and another that’s just convenient. Both spaces feel like home to her. Both know her work. Both give her what she needs, just differently. Home isn’t about one perfect location. It’s the practice. The work. The act of showing up.

That’s a completely different way to think about creative space. Not as something you build once and guard from disruption. But as something that can exist in multiple places, that travels with you, that doesn’t need perfect conditions to function.

Trudy’s practice proves that divided attention doesn’t always mean weak focus. That moving between spaces can create presence instead of killing it. That home doesn’t have to be one single place to be real.

To see more of Trudy’s work and follow her practice, connect with her through the links below.