Cecelia Wilken Grew Up In A Family Of Artists But Had To Lose Everything To Find Her Own Voice

👁 67 Views

At Arts to Hearts Project, we’ve spent years creating publications that give artists space to be seen, to be heard, to share work that matters. We’ve built platforms where creativity isn’t just displayed it’s celebrated. Artist spotlights, themed collections, studio visit books, exhibitions that bring communities together.

But among everything we do, there’s one publication we hold closest to our hearts: Arts to Hearts Magazine.

There’s something different about the magazine. Something more intimate. More intentional. It’s where we get to slow down and really explore themes that shape how we live, how we feel, how we understand the world around us. Each issue becomes a conversation not just between us and artists, but between artists and readers, between the work and the people who need to see it.

We’ve published 11 issues so far. And honestly? We’re not stopping. We’ll keep creating more because our artists love it, our community loves it, and when something resonates that deeply, you don’t let it go. You keep building. You keep exploring. You keep making space for the work that needs to exist.

For Issue 11, we chose a theme that felt both universal and deeply personal: Life. Not life as we’re told it should be Instagram-perfect, carefully curated, always ascending toward success and happiness. But life as it actually unfolds. Messy. Complicated. Beautiful and brutal in the same breath. Life that includes joy but also grief. Growth but also decay. Beginnings that come from endings. Transformation that requires loss.

We wanted artists who understood that life isn’t one-dimensional. That to truly live means feeling everything the light and the dark, the comfortable and the unbearable, the moments that make you grateful and the ones that break you open.

The submissions we received were extraordinary. Artists from everywhere sent work that didn’t shy away from difficulty. Work that explored what it actually means to be alive not just existing, but feeling deeply, surviving loss, finding beauty in places we’re taught to avoid.

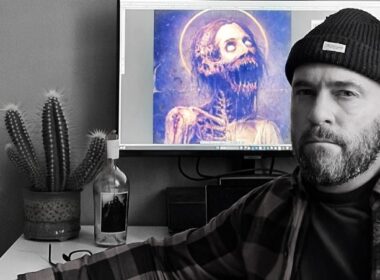

And the artist we’re introducing to you today the one whose work stopped us completely when we saw it is one of the selected artists for Issue 11.

Cecelia Wilken creates paintings that do something most art doesn’t: they make death feel approachable. Her work delicate floral forms paired with animal skulls, ghostly transparent subjects set against natural landscapes, beauty and decay existing in the same breath invites you to sit with mortality in calm, peaceful ways.

When we first saw her paintings, we knew she understood what Life actually means. Not just the bright parts. All of it. The loss, the grief, the transformation, the quiet acceptance that nothing lasts forever.

Her work doesn’t repel you with gore or violence. It draws you in with beauty, then shifts something underneath. She finds moments where life and death intersect naturally. Sometimes highlighting decay overtly. Sometimes using transparency and ghost-like qualities for softer symbolism. Always pairing difficult subjects with natural settings to make them accessible.

Before you get to know Cecelia through this interview, let me tell you what brought her to this work.

Cecelia grew up surrounded by art. Her father was a professional artist. Her grandmother was an avid oil-painting hobbyist. Art was everywhere in her childhood. But instead of that access making creation easy, it paralyzed her. She suffered from extreme perfectionism, felt she wasn’t “good enough,” and eventually stopped creating altogether.

She joined the US Army as a medic out of high school, thinking her purpose in life was to help others. But she was injured and medically separated from service. Then she became a parent. And in that convergence of loss and new identity, something inside her broke open. She fell into deep depression. Lost the person she thought she was supposed to be.

And that’s when she returned to art. Not because she suddenly felt ready. Not because the depression lifted. But because she needed a way to survive. To connect with her inner child. To cope with perfectionism, depression, anxiety that threatened to swallow her.

Art became survival practice. And she never stopped. That practice snowballed into a full-blown career. She’s exhibited widely oddity-themed events, contemporary galleries, fine-arts showcases, small local pop-ups. And she’s experienced the full range of reactions to her work. Pure disgust. Fear. Immense sadness. Shock. Awe. All of it.

Early on, negative comments felt like attacks on her soul. But over time, she learned something essential: viewers see what they need to see in her work. Their reactions—even disgust, even fear—reflect their own lives, their own relationship with mortality. Every emotion became validating rather than devastating.

What also drew us to her work is how it’s evolved. She’s always painted skulls, bones, florals. But now there’s deeper intention behind every choice. She approaches pieces with specific emotions in mind hope, peace, grief. She starts with a feeling and carefully plans around it, choosing subjects that symbolize those emotions. The subject became secondary to the feeling, whereas it was the opposite when she started.

Let’s get to know Cecelia through our conversation with herV exploring how she paints mortality with peace and what happens when you approach darkness with curiosity instead of fear.

Q1. Could you share your background where you grew up, how you first began creating art, and the moment when painting became central to your life and practice?

Art was something I was deeply interested in as a child. I grew up surrounded by art and artists. My father was a professional artist, and my grandmother was an avid oil-painting hobbyist. However, I suffered from extreme perfectionism and felt I wasn’t “good enough,” so my relationship with art stagnated. Eventually, I stopped creating altogether. I joined the US Army as a medic out of high school, thinking that my purpose in life was to help others. Unfortunately, I was injured and was medically separated from service. After my injury and after welcoming our first child, I sort of lost my identity and fell into deep depression. With the help of my spouse, friends, and therapist, I returned to art and creation as a way to connect and nurture my inner child and use it as a practice in coping with my perfectionism, depression, and anxiety. I never stopped, and my practice snowballed into a full-blown career.

Q2. Much of your imagery juxtaposes beauty with the macabre delicate floral forms, animal subjects, and moments that suggest mortality. How do you deal that balance between attraction and unease in your compositions?

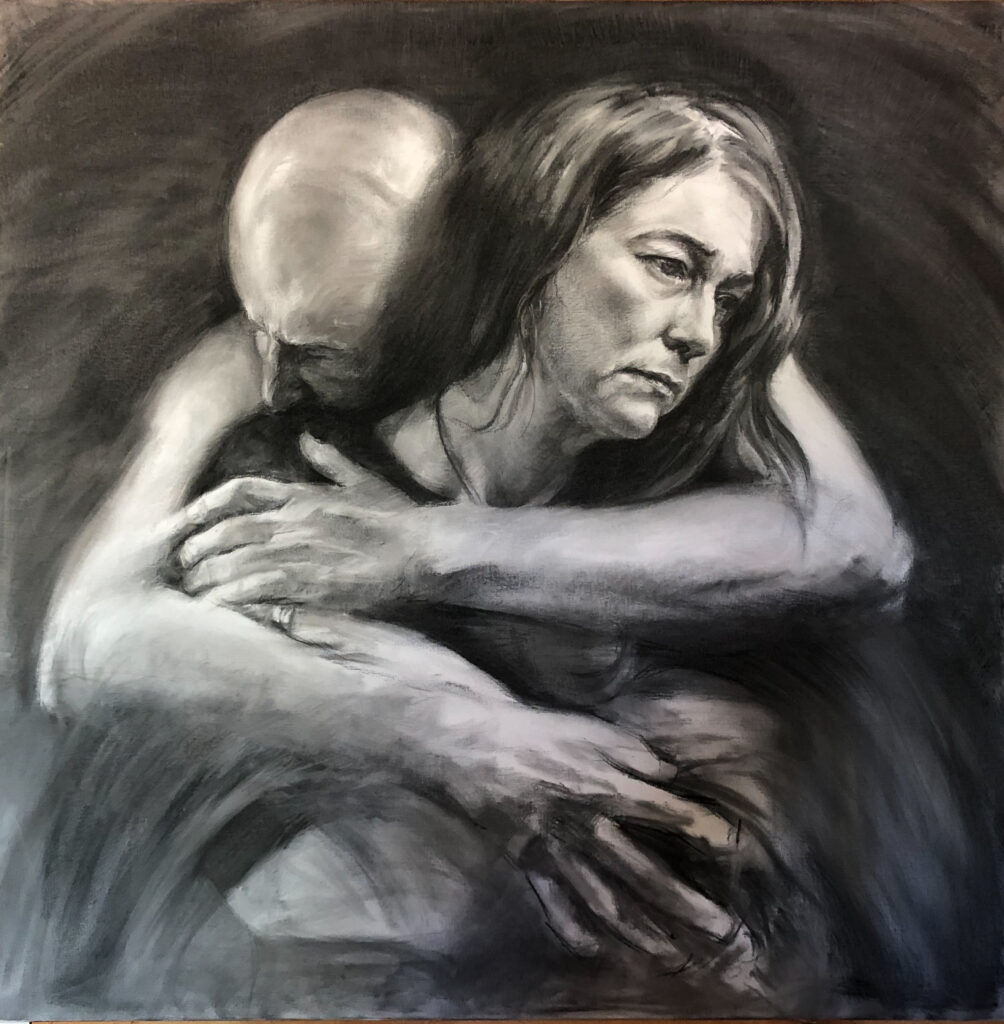

There is a delicate balance in making themes of death and decay feel approachable while maintaining the harsh reality of their authenticity. When creating my compositions, I try to find moments where life and death intersect in ways that feel natural and true. Sometimes I highlight various stages of decay and lean into the cycle of impermanence. It can have a very powerful effect when decay is presented so overtly. If the piece calls for softer symbolism, I allude to death or decay by giving subjects transparency or ghost-like qualities. When paired with natural or floral settings, I think it really drives my vision of making the uncomfortable more accessible. I really try to invite viewers to share space with the uncomfortable in calm and peaceful ways – not necessarily disgust or disdain. That’s why I don’t often use excessive blood or allude to violent deaths in my pieces because I think it distracts from the overall message I hope to convey.

Q3. You began taking your art seriously after medically separating from the military and becoming a parent. How did that life transitions influence the way you think about vulnerability, resilience, and presence in your work?

I really struggled with these life transitions. I had very carefully planned out visions for what my future would look like and how I was supposed to feel about it. Putting so much emphasis on these expectations really crippled me when those plans fell apart and when motherhood, while joyous and beautiful, was at times equally painful, heavy, and difficult. I carried so much shame and guilt around these “failed” expectations, and they ate away at me. Leaning into and admitting these hard truths to myself has actually led to my personal growth and deepened the meaning of my work. Through my practice, I can sit and view the pieces of myself that I struggle with from many different angles. I can bring softness, understanding, and peaceful contemplation to the parts of myself I shy away from and in turn, I hope to inspire that in others.

Q4. Many artists feel that certain elements like the presence of animals, flora, or shadows recur for reasons that emerge slowly over time. Are there motifs or gestures you find returning across different bodies of work?

I find myself revisiting flora and fauna from the Sonoran Desert. I grew up in Arizona and there is always a piece of me that aches for that wild, harsh landscape. It was a refuge for me as a child, and I never feared the snakes, spiders, scorpions, or coyotes that roamed the land around my childhood home. That childhood curiosity fueled my passion for nature and understanding our roles as caretakers of the land. My artwork encourages me to conduct extensive research on ecosystems and the relationships between coexisting plants and animals.

It is important for me to understand the subjects that I include in my pieces, and often, there are symbolic or very intentional reasons why certain subjects are paired together.

Q5. You’ve exhibited widely across juried shows and expos nationwide. Has being part of different creative communities influenced how you think about your work’s themes or presentation?

I feel that my work really overlaps with many different communities. I’ve attended oddity-themed events and shows, contemporary events and galleries, strictly fine-arts showcases, as well as small local pop-ups and crafting markets. As a result, I have experienced a wide range of reactions to my art, and it has really helped me figure out how to present myself in a way that is authentic and real, yet palatable to the crowd I find myself in. It is a delicate balance, but ultimately, I have found that my work is simply not for everyone, and I am more than okay with that. It is more important to me to create what feels true to myself than what a gallery, an event, or even a crowd expects from me. I think most people crave authenticity, and they can see it reflected in my work.

Q6. When you encounter unexpected responses from viewers interpretations you didn’t anticipate how does that conversation shape your view of the work?

Because of the nature of my work, I get a lot of mixed reactions. They vary from pure disgust and fear to immense sadness, shock, and awe. I’ve seen them all. I really struggled with negative comments when I was first stepping out into the art scene. Each comment felt like an attack on my very soul, and it has taken a lot of time and reframing for me to appreciate every interaction, even the negative ones. I’ve learned that most viewers see what they need to in my work – the reactions they have are often reflective of their own lives and experiences. Images of death and decay can make viewers reflect on their own morality and ultimately how they have lived. Those emotions can be very scary for some. Every emotion, even disgust and disdain, is actually a very quite validating reaction for me as an artist.

Q7. In your creative process, do you find yourself drawn to certain emotional states curiosity, tenderness, melancholy more than others? How do you channel those states into the work?

I am a deeply feeling individual, and I feel all my emotions with a lot of intensity. I think that makes me very contemplative and sensitive to the emotions I put into my work. Sometimes it actually works against me. If I’m working on a particularly heavy piece, maybe it’s a subject or a feeling that brings up a lot of push-back in me or is maybe triggering in some way, I have a hard time working on it. I have to be in a reflective, rather than reactive, state to really channel those feelings in a painting. I’ve had pieces sit on my easel or in the back corner of a closet for months, simply because they bring up heavy emotions in me.

Q8. Looking back at your earlier work versus what you’re making now, what shifts in visual language or emotional focus do you notice most distinctly?

I had always played around with themes of death and decay – painting skulls and bones and florals. But I think my work has become more intentional and nuanced. Instead of just a skull with flowers for the sake of skulls and flowers, there is a deeper hidden meaning in my work now. I approach pieces or series with specific emotions or memories in mind, like hope, peace, or grief. Often, I start with a feeling and carefully plan around it, choosing subjects that invite or symbolize those emotions. I let my decisions be carried by emotion rather than subject matter. I would say that now the subject is secondary to the feeling, whereas it was the other way around when I first started.

Q9. What advice would you give to emerging artists who want to explore difficult emotional terrain in their work to make art that feels honest, layered, and meaningful without relying on surface sentiment?

I think many artists are hesitant to explore more deeply. They find the thing that feels nice and easy and rely on that to carry their practice. Which is totally fine! But for those who feel maybe stagnant in their practice, or who want to add more emotion and depth to their work, or maybe want to connect more to their practice itself, my recommendation is to open that door of emotion with curiosity rather than fear. That shift really comes from within, and that can feel scary at first. But it is so liberating once you lean into it. Go for it. Be curious and gentle with your experimentation. Let it carry and guide you into the unknown places within yourself.

Wrapping my conversation with Cecelia, I kept thinking about how she described returning to art: not from strength, but from necessity.

She grew up surrounded by artists, but perfectionism silenced her. She joined the military to help others, then injury ended that path. Motherhood arrived. Depression followed. Everything she’d planned dissolved. And in that dissolution, she found her practice.

What strikes me most is that her work doesn’t exist despite the breaking—it exists because of it. She paints mortality with peace because she’s lived through loss. She pairs decay with beauty because she understands they’re inseparable. She invites viewers into discomfort because she’s learned to sit there herself.

Her evolution tells the story: she used to paint skulls with flowers because they looked interesting. Now she starts with emotion—grief, hope, peace—and lets that feeling choose the subjects. The visual became secondary to the truth. That shift changes everything.

Here’s what Cecelia’s work taught me:

Sometimes you have to lose everything you thought you were before you can create what you’re actually meant to make. Sometimes the plans falling apart isn’t failure it’s the clearing that allows truth to emerge. Sometimes depression and injury and failed expectations aren’t obstacles to your practice. They become the practice itself.

And if you want to make work that feels honest, layered, meaningful not surface level sentiment but real emotional depth you have to open the door you’ve been keeping closed. You have to approach the parts of yourself that scare you with curiosity instead of fear.

That’s terrifying. I know. Sitting with your own darkness, your own grief, your own shame, that takes courage most of us don’t have. But Cecelia’s showing us what’s possible when you do it anyway.

Work that makes mortality feel approachable. That invites people to sit with discomfort peacefully. That brings softness to the parts we usually hide. That creates space for viewers to see what they need to see and feel what they need to feel without being told how to respond.

Follow Cecelia through the links below to see what happens when someone paints truth instead of expectation. When someone uses decay and death to create peace rather than disgust. When someone lets emotion lead and subject matter follow.