Do You Believe Bigger Studios Make Better Art? Kathrina Looser Thinks Differently

👁 31 Views

We’ve spent seven volumes of our Studio Visit Book series walking into every kind of creative space you can imagine. Sunlit rooms with windows that stretch wall to wall. Tiny corners carved out of shared apartments. Garages that still smell like the cars that used to park there. Kitchen tables that double as desks during the day and get cleared for dinner at night. And if there’s one thing we’ve figured out by now, it’s that there’s no such thing as the perfect studio. There’s just the studio that works for the person using it, and sometimes that doesn’t make sense to anyone else. And that’s fine.

For Volume 7, we chose “Home” as our theme. We wanted to know what that word really means to artists whose work isn’t just a hobby or a side thing, but something that shapes their entire lives. Not the poetic, Instagram-caption version of home. The real version. Where do you actually feel like you can breathe? What space holds you when everything else feels like it’s falling apart? Where do you keep returning, not because it’s easy or comfortable, but because something about it just feels right?

When Kathrina Looser’s submission came across our desk, we stopped what we were doing and read it twice. Because her studio? It’s underground. And we don’t mean a basement apartment with those small windows near the ceiling that let in a sliver of daylight. We mean actually underground. A vaulted cellar carved into stone in Switzerland. The kind of space that feels more like stepping into a cave than walking into a workspace.

Think about that for a second. No phone reception. No natural light. Thick stone walls. Damp air. It’s the kind of place most people would visit once, feel slightly claustrophobic, and start mentally planning their exit. But Kathrina? She’s been working there for fifteen years. By choice.

The space has history, and not the charming kind. Metal hooks still hang from the walls, remnants from when the cellar was used to butcher and hang meat. Can you picture that? Walking into your studio and seeing the hardware that once held animal carcasses. Later, those same walls witnessed underground parties, the kind that happen in cities late at night when people need somewhere the outside world can’t reach. Now, those walls witness something entirely different. They witness Kathrina showing up, day after day, year after year, making photographs and screenprints in a space that has seen slaughter, chaos, and now, quiet focused work.

And here’s something: she doesn’t drive there. She bikes. Rain, snow, summer heat, winter cold doesn’t matter. The journey itself is part of the process, a deliberate shift from the world above ground to the work waiting below. It’s not about exercise or being eco-friendly. It’s about transition. About marking the moment when regular life ends and studio life begins.

When she finally gets there and descends into that cellar, she doesn’t just walk in and start working. There’s a ritual. A very specific one. Light on. Then she goes straight to her work apron this thing that’s covered in fifteen years of paint splashes, reds and blues and yellows all layered on top of each other until the fabric itself looks like a piece of art. She puts it on. Then she lights five candles. Every single time. Not four. Not six. Five. In the same holder. Same sequence. Every session.

It’s not superstition or aesthetics. It’s structure. Without that ritual, the studio is just a damp basement with weird history. With it, something shifts. The space transforms. The artist appears.

Kathrina didn’t end up here by accident or because it was all she could afford. She’s not making do with what fell into her lap. She studied art formally for five years at Zurich University of Arts. She interned in New York at a design studio, the kind of place most people would be thrilled to work at permanently. She had options. Credentials. A clear path in front of her if she wanted to take it.

But somewhere along that path, she realized something crucial: responding to client briefs, no matter how prestigious or well-paid, wasn’t going to fulfill what she needed creatively. She learned a lot, sure. But something essential was missing. Freedom. Real freedom. The freedom to follow an idea all the way through from start to finish without someone else’s vision bending it, without having to justify every creative choice, without compromise.

That’s when she decided to call herself a visual author instead of a designer. The difference matters to her. Designers execute someone else’s vision. Authors own the whole thing from the very first idea to the final piece that comes off the press. Every decision, every mistake, every success, it’s all hers.

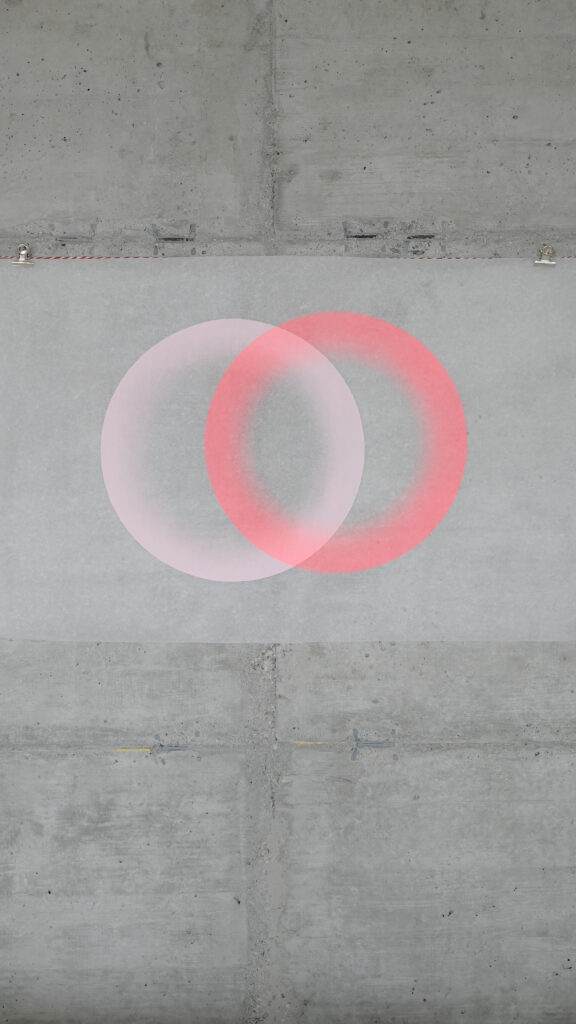

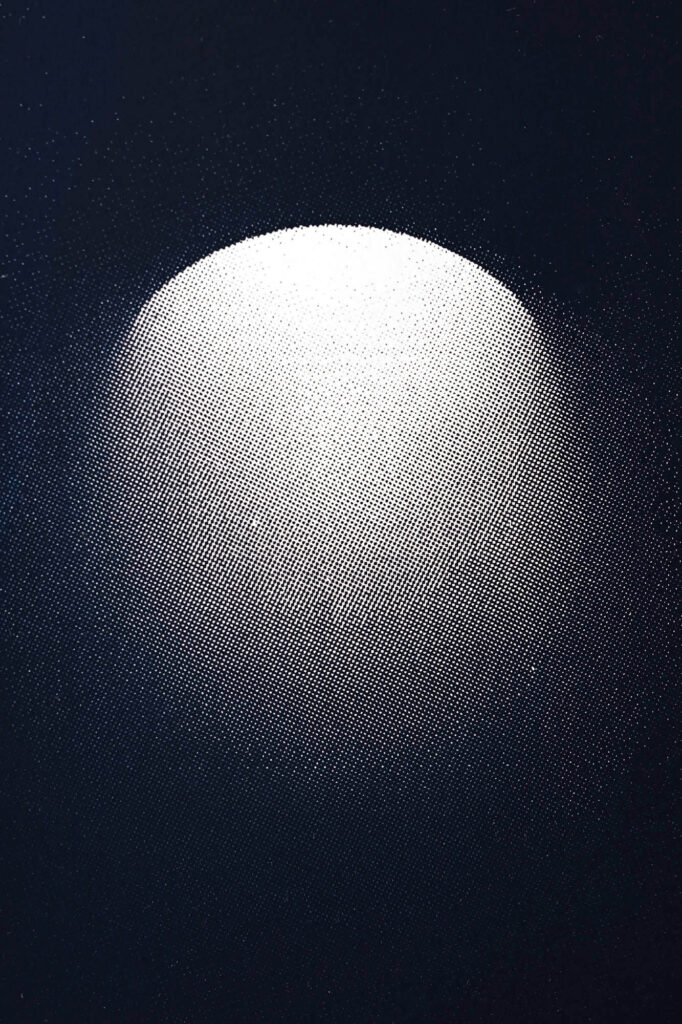

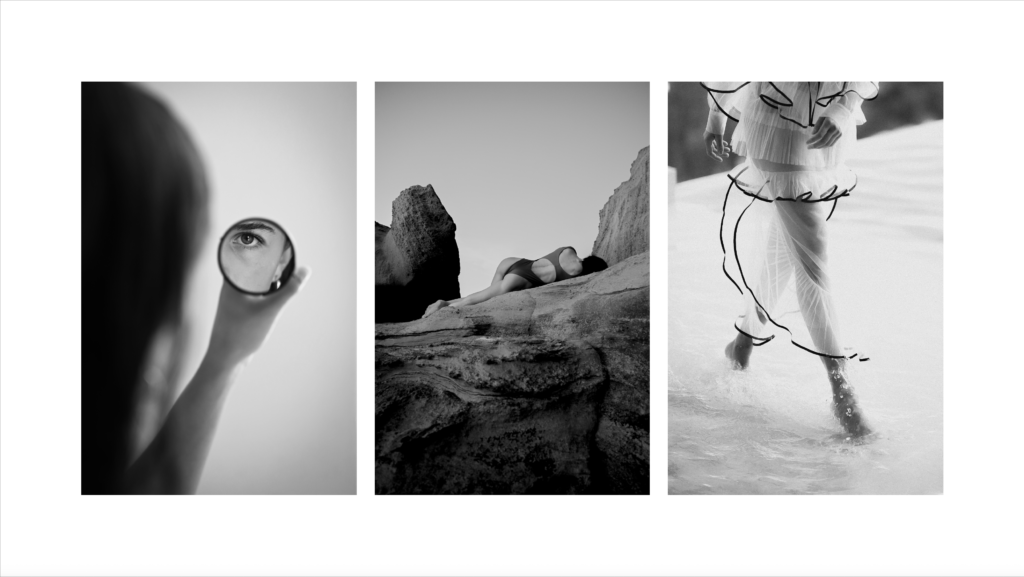

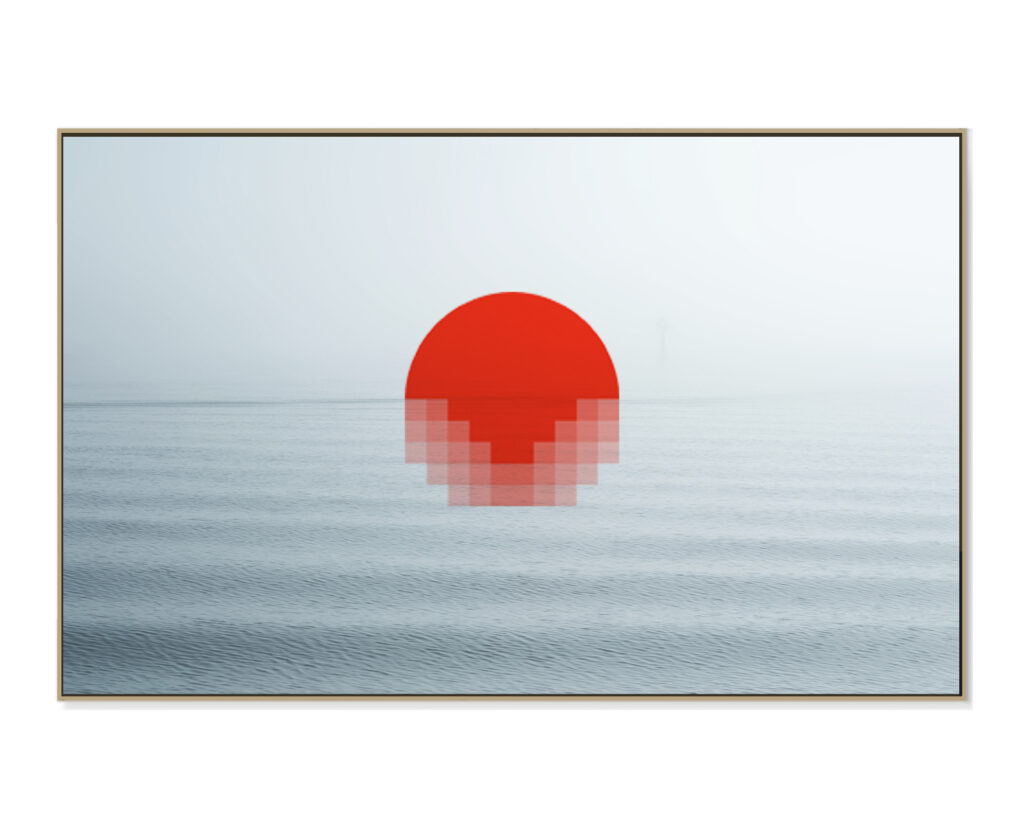

If we talk about her mediums, photography and screen-printing are the things she wanted to work with not because they’re popular or because there’s money in them, but because they let her do what she’s always been interested in: taking something complicated and breaking it down until only the important parts are left. She works backward, adds layers one at a time, and lets the materials show her things she didn’t expect.

And all this happens in that cellar. Even with the damp air. Even with the hassle of packing everything up after every session and carrying it home. She loves that place. The stone walls, the darkness, the weight of it. The fact that her phone doesn’t work down there. The old meat hooks still hanging like quiet witnesses. Most people would look at that space and see problems to fix. She looks at it and sees home. Her studio home. The place where she can think clearly, work honestly, and build something that lasts. Fifteen years of biking there through rain and snow. Fifteen years of lighting the same five candles when she arrives. Fifteen years of the same worn apron covered in splashes of color. And she’s not leaving. That cellar has become hers in a way no bright, modern studio with big windows ever could.

Now let’s hear from Kathrina herself about what actually goes on down there, how she’s made that cave work, and what those fifteen years in the dark have taught her.

Q1. I’d love to hear about your studio as it is right now, what’s present on the walls or tables, and what kind of atmosphere surrounds you while you work.

My studio is underground a vaulted cellar that feels like a cave. It’s a place of retreat, where focus deepens and distractions fall away. I bike there, letting the journey mark a shift from the outside world into the work. With no phone reception, I’m alone with my thoughts. Surrounded by stone, light, and color, ideas are given time to take shape. Here, the act of making matters more than the outcome; presence matters more than speed. Within these old walls, I find a rhythm that’s hard to access elsewhere. It feels like a quiet luxury — to work with clarity, to enter flow, and to create work that’s honest and meaningful, whether through photography or limited-edition screenprints.

Q2. You identify as a visual author someone who brings ideas to life through image and form. Can you share how this idea first took shape for you, and how it led you into making art as a daily practice?

After completing a five-year education at the Zurich University of Arts (ZHdK) and completing an internship at C&G Partners in New York, I realized that traditional service-based work — responding to client briefs — wasn’t what truly fulfilled me. While I learned a great deal, something essential was missing: the freedom to fully follow my own ideas. Over the past fifteen years, it has become increasingly clear to me that I’m a born artist. I want to develop my own concepts and carry them through from the initial idea to final realization, taking responsibility for the entire process rather than simply reacting to external demands. Seeing myself as a visual author allows me to express what’s happening internally — thoughts, emotions, and questions that are best communicated through image and form. I consider myself a creative visionary, driven by an ongoing flow of new ideas, by the desire to create, and by meaningful connections with others. This constant process of exploration and connection is what fuels my daily practice.

Q3. Your work flows between photography, screen printing, and visual messaging. When you think back to your earliest creative experiences, how did those moments shape the language you use now?

My earliest creative experiences were very simple. Drawing, stamping, cutting things out, collecting images, making collages — mostly driven by curiosity, not by intention. I was always fascinated by printing, early on. Letterpress, stamps, the idea of working in reverse and letting an image transfer rather than be made directly. I experimented with intaglio techniques like etching and drypoint — scratching into plates, inking them, pulling prints. That physical, time-based process really stuck with me. In my foundation course, I tried everything: sculpture, sketching, life drawing. But I kept coming back to photography. Working analog, spending time in the darkroom, experimenting with light, chemistry, and the camera obscura brought a lot of those early interests together. Looking back, it feels like a very natural progression. The work I do now still comes from that same curiosity — an interest in reduction, translation — with the photographic image and graphic reduction at the core of my visual language.

Q4. How do you enter the studio when a day’s work begins is there something you do to settle in before you shift into making, whether it’s arranging materials, looking through images, or remembering an idea?

I actually follow the same routine every time. I switch on the light, then I go straight to my work apron. Over the years it’s become covered in colorful splashes and printed traces, almost turning into an artwork itself. When I put it on, there’s a real shift — it’s the moment I step into being Kathrina Looser as an artist. After that, I do one more thing that never changes: I light five candles in their holder. It’s about setting the atmosphere the way I need it to be. That small ritual helps me arrive in the space, slow down, and transition into making. I do it every single time.

Q5. Do unfinished works remain visible in your studio? If so, how does living alongside works in progress shape the way you come back to them, day after day?

I don’t usually leave unfinished works in the studio. Because of the humidity, paper and printed pieces wouldn’t last there. So I take everything home with me. Living with the works outside the studio gives me distance. I can look at them more quietly, without the pressure of production, and think about how they might continue. Some of them then find their way back into the studio for another phase of work — going back and forth like that has become part of my process.

Q6. Many of your works feel like ideas made visible, whether layered text, imagery, or printed surfaces. How does intuition guide you when a piece first starts to take form in the studio?

“Follow your intuition” sits at the very top for me. Intuition plays a clear, central role, especially at the beginning of a new body of work. I often start with a vision board, usually at the beginning of the year, to get a sense of the themes I want to focus on. From there, a working title begins to form and acts as a kind of anchor. I then move into a playful phase of making. The process often shifts from the initial chaos of brainstorming to a sharp, focused idea that eventually condenses into a series.

Q7. What tends to stay out in the open in your studio, and what do you keep tucked away? What do those choices say about your process?

The studio is very present in my process. It’s a basement space with old, history-filled walls and traces of earlier lives. Large metal hooks still hang from the walls — once used for hanging meat, later part of underground party nights. I’ve been working there for over fifteen years, and being surrounded by those layers of time and history strongly shapes how I think about material, time, and process. What stays visible are my tools and colors. All my paint cans are stacked into a large color palette, almost like a wall of possibilities. It helps me respond intuitively to color. My tools are laid out openly as well — like a buffet I can move through while working.

Q8. How does light natural or artificial interact with the surfaces you work on in photography and print? Does changing light influence your sense of a work’s direction within the space?

In photography outside the studio, light is everything — it’s all about good light. Inside the studio, though, daylight doesn’t really play a role. Because the space is underground, natural light has little influence on the work. What matters more is atmosphere. Candlelight helps me settle into the space, while any working light I use is artificial and very deliberately placed, especially when dealing with photographic or printed surfaces.

Q9. When you share work on platforms like Instagram, how do you feel the studio behind the images the textures, discoveries, and unfinished moments continue to live with viewers in ways that matter to you?

I really love using Instagram to document process. My website is where the finished works live, and exhibitions are where the pieces come together in physical space. But showing the process feels just as important to me. I enjoy filming my workflow and sharing how things come into being — the in-between moments, the decisions, the discoveries. Posting small stories about the making allows the studio, the textures, and the unfinished stages to stay visible. For me, that documentation has become an essential part of my creative practice.

Q10. How has your relationship with your studio space changed over time has it become quieter, more confident, more experimental, or something else entirely?

Earlier in my career, the studio was mainly a place to fulfill commissions or to reproduce already developed series, often for my webshop. Today, the focus has shifted. My work is more centered on serigraphy as a unique, exploratory process. There’s a playful, joyful engagement with color and form, and something new is constantly emerging. Being down there now, I often experience a sense of flow — a mix of creative passion and quiet happiness. The work feels both everyday and magical at the same time. Ultimately, the studio has always been a space for reconnection with myself and my thoughts, taking on an almost meditative character while I work.

Q11. What advice would you give to artists developing their studio practice, based on what you’ve learned through your own work?

I would say: give yourself time, and protect your curiosity. A studio practice doesn’t need to be fixed or perfectly defined early on. It grows through doing, through repetition, and through allowing things to change. Trust your intuition and build rituals or conditions that help you arrive in the work. Reduce distractions as much as you can and create a space where you feel safe to experiment. Not everything has to lead to a finished piece — some things are valuable simply because they move your thinking forward. Most importantly, stay connected to why you started making work in the first place. That connection is what sustains a practice over time.

Size: 180 × 120 cm (70.9 × 47.2 in)

After talking to Kathrina, we found ourselves thinking about her studio differently than we expected. Not as a space with problems she’s solved, but as a space she’s decided to love exactly as it is.

Because honestly? On paper, that cellar shouldn’t work. It’s underground, damp, dark, and requires her to pack up everything at the end of every session and carry it home. Most people would’ve moved on by now, found somewhere brighter or more convenient. But Kathrina stayed.

Fifteen years of biking there through rain and snow. Fifteen years of the same ritual when she arrives. And what she’s built in that time goes beyond the prints and photographs she’s made. She’s built a practice that actually holds her.

What stuck with us most is how she doesn’t fight the space anymore. The lack of natural light? She works with candlelight and places artificial light where she needs it. No phone signal? Perfect. Fewer distractions. Humidity that forces her to take work home? She’s turned that into part of her process. Living with the work between layers has become valuable, not annoying.

There’s something really grounding about watching someone stop waiting for perfect conditions and just work with what they have. Kathrina didn’t need a dream studio to build something meaningful. She needed a space she could show up to consistently, a ritual that helped her transition into the work, and the willingness to adapt instead of complain.

Her story reminded us that home doesn’t have to look a certain way. It doesn’t need big windows or Instagram-worthy aesthetics. It just needs to be a place where you can do honest work, where you feel like yourself, and where you’re willing to keep showing up even when it’s not easy.

Fifteen years in that underground cellar taught Kathrina something most artists are still looking for, how to build a practice that doesn’t depend on perfect circumstances. Just commitment, ritual, and a space that’s become completely, undeniably hers.

To see more of Kathrina’s work and follow her practice, connect with her through the links below.