Beneath the skin lies a story of everything | Marina Schulze

👁 51 Views

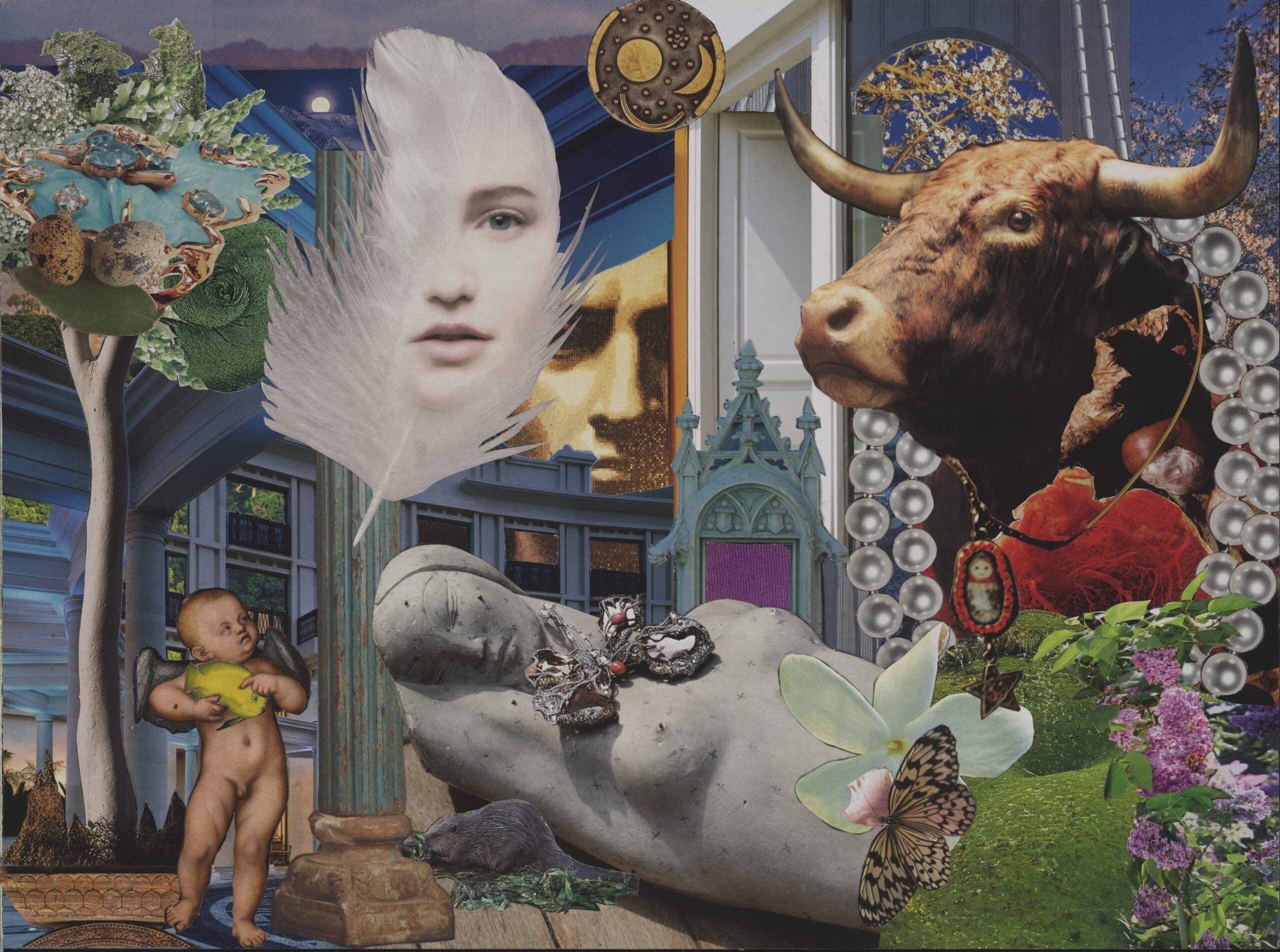

Marina Schulze was born in Berlin in 1959 and calls her work a lived biography. In this interview, she speaks with quiet certainty about how a life threaded through motherhood, theatre, myth, and feminist study has led her to a very deliberate way of constructing collages and drawings that question who defines the feminine and for what purpose. She describes herself as someone who has always “functioned in images,” and as she speaks, it becomes clear that her practice has grown out of decades of absorbed scenes, dreams and memories that are still very much alive in her.

She tells us about her grandmothers, who through the ancient tradition of oral storytelling opened up her visual thinking and the world of fairy tales, about her grandfather and her parents, who through their professions led her into an awe-inspiring reality. These early impressions form the landscape from which her visual narratives later emerge.

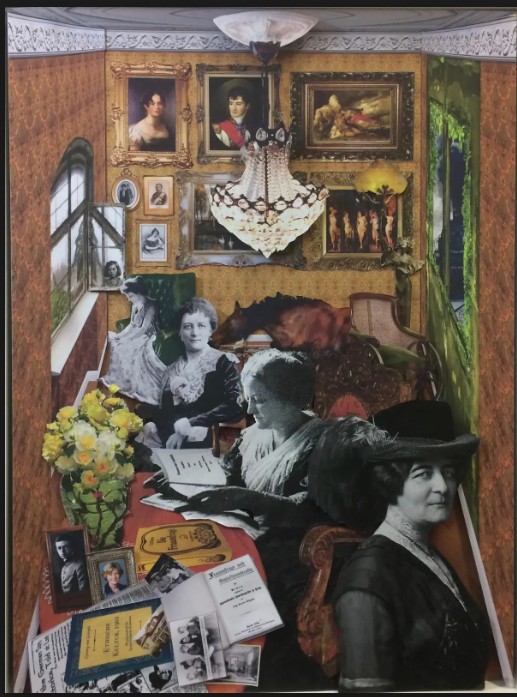

Throughout the interview, Marina explains how literature, theatre studies, art history, and critical psychology shape the way she looks at people, structures, and assumptions. She speaks about learning to examine research itself, to question motives and hierarchies, and how this training prepared her for the close, detail-oriented gaze that now guides her work. We learn how she approaches her analog and 3D collages with almost architectural care, researching each figure and object, adjusting proportions, and building layers of paper until a scene feels truthful to its own internal logic. She walks us through the precision involved, from gathering source material to constructing miniature elements by hand so the final piece tells a complete story within a single frame.

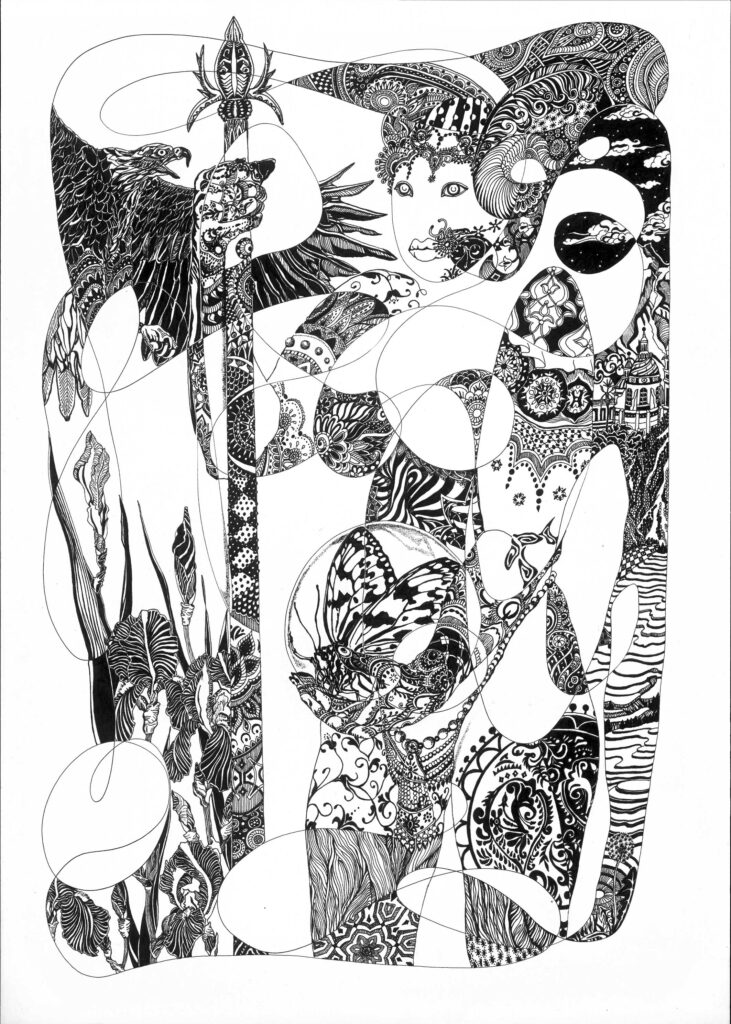

Marina also speaks about her intuitive line drawings, which begin without a goal. She follows a wandering line until, sometimes days later, a figure or situation surfaces. This way of working mirrors how she manages the fragmentation and overload of contemporary life: by giving space for something meaningful to appear in its own time rather than forcing certainty.

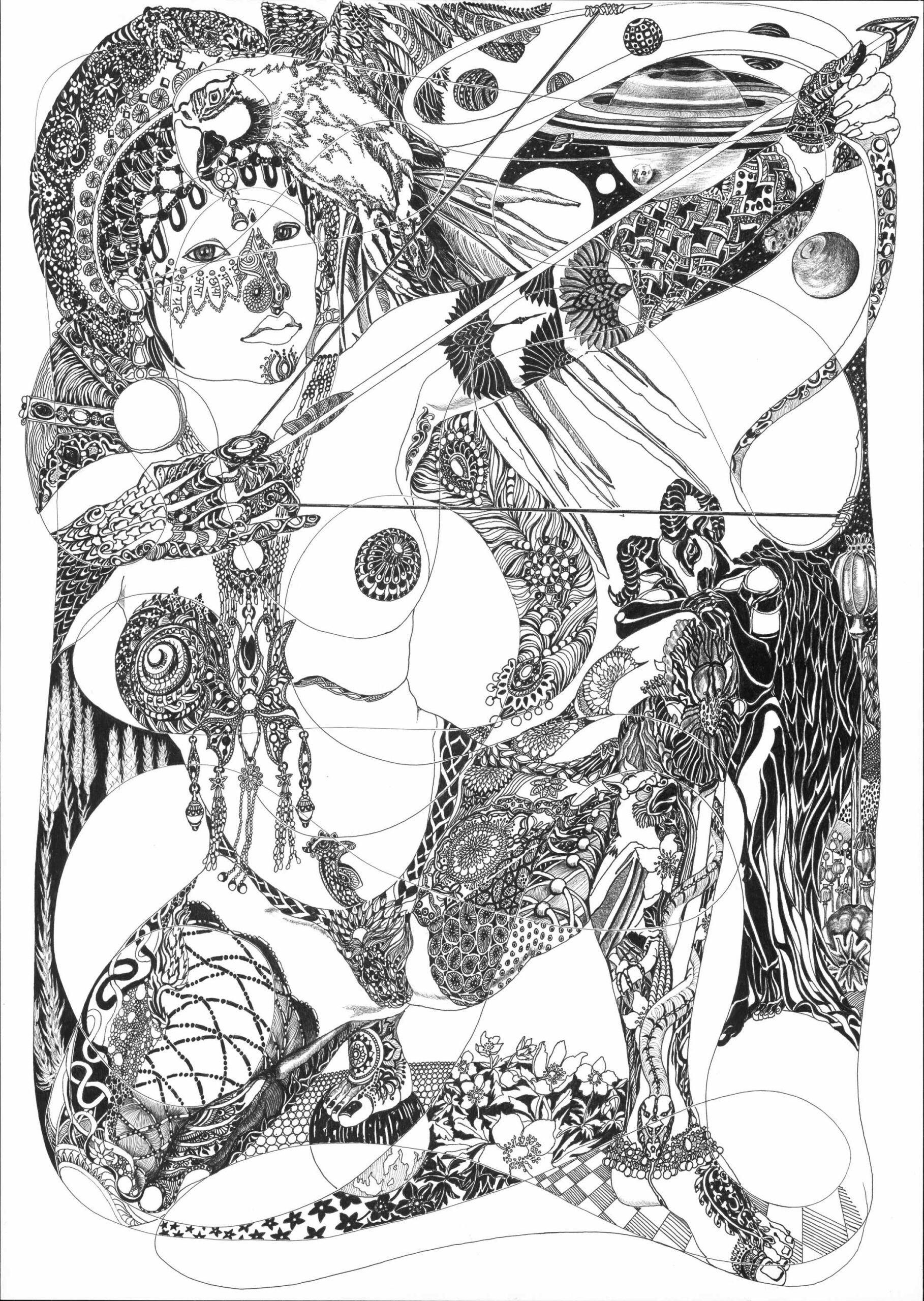

What becomes clear is how gender research and creation myths permeate her figures. She questions patriarchal narratives, reimagines inherited myths, and considers what our relationship to life and death might look like if shaped by female divinities instead of punitive gods. Her imagery carries these thoughts forward, offering alternative stories without sermonizing.

By the end of the conversation, we come away with more than an outline of her exhibitions or achievements. We gain insight into how a lifetime of listening, reading, studying and observing has settled into a practice that uses handmade processes to address the tensions of the present. Her collages and drawings become places where stories, research and lived experience meet, offering a way to look at the world with more nuance and more courage.

Marina (*1959, Berlin) sees art as lived biography. As a self-taught visual artist, she has developed her own visual language that draws on motherhood, theatre, and myth. Her works have been shown in Berlin, Toronto, and New York, published in international art magazines, and in 2024, she was selected as a finalist for the Women United Art Prize. She is a member of bbk Berlin and has participated in feminist exhibition projects. Her artistic journey is a quiet resistance against the shaping of the female principle – and an invitation to reflect. Beyond exhibitions, her practice includes stage design, graphic work, and curatorial projects. Her image worlds, analogue and figurative, unfold into narrative spaces shaped by a new surrealism – one that does not dream, but exposes.

1. How did the combination of literature, theatre studies, art history and psychology guide the way you construct visual narratives today?

I function in images. Always have. What my senses bring me creates images. They are striking and sometimes overwhelming. When someone tells of an accident, I see it as a film before me. I have a photographic memory. I experience dreams like long films; sometimes my dreams also seem to be harbingers. It is worth listening to them. Dreams have told me I am pregnant or that something terrible has happened to a friend. I have also painted dreams. It is not easy to capture such a film in a single image. Before my passion for literature, theatre, and other sciences, there was something essential in my biography: grandmothers whose stories evoked images of their childhood in me—of farms and breweries, of tunnels one had to dig through snow to reach another house, of ball lightning racing through the apartment and disappearing in the sink.

Of huge tables with many people around them, cruel punishments, parents you had to address formally, and the absence of sugar and toys in everyday life. Of two wars and brave mothers fleeing with their children. Then there was a grandfather who spoke little, a cook by profession, dressed all in white with a cap on his head. He took me to a land of plenty where the pots were so enormous that men had to climb up to their rims on ladders, and ladles so large I could have sat inside them. Images full of magic for a five-year-old. Naturally, my grandmothers read me countless fairy tales. I learned to read myself at the age of five and never stopped. I still love and collect fairy tales, legends, and creation myths from all cultures of the world, and have always felt their cruelties as truths that can be redeemed through the work on the necessary miracle. Perhaps that is the moment I became an artist… Another powerful influence on me is my parents’ profession, both classical solo dancers.

I had very young parents and was often present at rehearsals and premieres. So to speak, I grew up on and behind the stage, where I reencountered my fairy tales and myths in old and new costumes. The memories of all these sensory impressions, meanings, and above all, the inner syntheses are a constant stream in which I swim when working with a piece. It is no wonder that I am a storyteller in my images. Of course, I did not grow up in a fairy tale. Reality and people have many faces, and I was already able to observe them as a small child. This sensitivity, along with my inherent curiosity and search for truth, led me at the age of 36 to study Critical Psychology. A then-unique institute at the Free University of Berlin, sadly long dissolved and banned, probably because it offered a truly enlightening, emancipatory course of study. With a critical eye, research methods, from the interpretation of results to history, philosophy, religion, and politics within psychology, were examined, as were the research goals and science funders. My studies are multipliers for layered perceptions that seek connections to the existing and the future. Like the parts of a collage. Like the meeting of accidental and deliberate lines in a drawing, creating something new: a chimaera.

Like all living things, chimaeras are made of many parts, so I learned to look closely. Hence, my detail-oriented gaze in my work, the psychoanalytic approach, and the critique of power relations. This, in turn, led me to my own studies of matriarchal research and the conviction that only the strict dissolution of patriarchy promises a future for humanity and the planet. Thus, throughout my work, all these ingredients from personal history and the studies they led to swirl, like in my grandfather’s kitchen, in a spiritual giant pot, and I scoop out the essential with a long ladle as ancient truths whisper to me. Only in retrospect does it become clear how strongly all these influences have shaped my approach to image formation, the blending of knowledge, memory, and imagination. My desire to capture the fragmented and multilayered in a narrative finds expression in my visual worlds.

What appears beautiful is subversive. What seems quiet speaks loudly.

Marina Schulze

2. In your 3D collages, what leads you to choose certain materials when you build spatial tension and perspective?

First, my love for paper. One can hardly exhaust all its possibilities within a lifetime. Then comes the subject on the one hand, and on the other, the real space of the frame or support. My first two 3D collages were each designed in a 3-centimetre-deep shadow box frame. As soon as a person, a living being, and their story interest me, I begin with research to develop an idea of how to summarise the entirety of facts and my interpretations into a single representation. What do I leave out, what must be included? When translating into an image, I am no longer a reporter or researcher—the image itself has its own truth. Then begins the collection of authentic imagery, or material that approximates the message and can translate it.

The proportions of figures and their relation to the environment must be adjusted, which I also do through digital image editing, as well as for perspectives on architecture and props. The next challenge is finding a print shop that can reproduce the original on paper as closely as possible to the original in the specified scale, so that the edited piece blends seamlessly. This process is quite elaborate and prone to errors. Once that is done and I feel it is coherent, the stage assembly begins, which for me is the 3D collage. I experiment with the sequence in which elements can and must be installed. This determines the type of support material on which the part will be mounted. The farther back in space a part should be, the thinner its support material; the farther forward, the thicker, as it then becomes more “graspable.” Sometimes this requires numerous layers of various cardboard and paperboard until the visually correct height relative to the environment is achieved.

As a rule, I try to glue everything separately: every chair, every open window sash, even the frames of paintings far back on the wall are placed in front of the mounted painting itself, which was glued to wallpaper I designed myself and that, in turn, was mounted on a support. Letters on the table and books are individual parts, each worked on. I mostly stick to paper/cardboard as the support material; it goes against me to mix plastic or other substances with a paper piece. From paper and its relatives, one can build everything—you have to figure out how.

3. Your intuitive line drawings begin without a set goal. How do you decide when a form has revealed enough for you to continue developing it?

It has never happened to me that an aimless line, at the latest after rotating the page, has not sufficiently revealed itself to be further developed. That is the beauty of such lines: one is free—even free to have no idea at all. It is only up to me if I cannot see what emerges from it. Then I must wait until the next day or the day after. Then suddenly I see the story in, around, before, and behind the line. Suddenly, there is a head, a belly, or a bird. The rest comes by itself, but it is always the aimless line that determines how far I can go beyond it.

4. What draws you to handcrafted processes at a time when visual culture is driven by fast digital production?

Handcrafted manufacturing processes fascinate me precisely because of their authenticity and the tangible connection between human, material, and time. While digital production primarily aims at speed, efficiency, and reproducibility, craftsmanship emphasises the individual, physical engagement with the material, which imparts a unique value to each piece. In an era where much is produced quickly, smoothly, and mechanically, craftsmanship remains the art of creating its own language with precision, patience, and skill—allowing human imperfections and thus character to show.

Especially as visual culture is increasingly dominated by digital means, my appreciation grows for the imperfect and the genuine, for the sensation of time that resonates in every handcrafted work. Craftsmanship is not a retreat into the past but a conscious counterposition and complement to the digital world, reflecting also sustainability and the relationship between humans and the environment. It is this deeply human, creative act that draws me to handcrafted processes and that gains new significance in an ever-accelerating digital culture.

I function in images. Always have.

Marina Schulze

5. How do the themes of gender research and creation myths influence the figures that appear in your collages and drawings.

The themes of gender research and creation myths profoundly influence the figures in my works. Gender research is an emancipatory tool to question and dismantle stereotypical role models and normative gender assignments. The patriarchal matrix is all-encompassing and destructive, like a corrosive poison. Deeply misogynistic, it is toxic to every peaceful, femininely perceived being. By femininely perceived, I mean every woman on this earth, every persecuted ethnicity, every queer way of life, every creature that wishes to live according to its nature.

Everything that the patriarchy negatively connotes is applied to these to control, exploit, abuse, and destroy them. This must end— and for the good of all that is feminine! Just as we cannot imagine a five-dimensional space because we have never lived in it, the absence of patriarchy is hardly conceivable. Yet we need this utopia to survive and to be able to stand in solidarity. With my art, I join the long historical line of female artists who have written, sung, painted, danced, and asked questions about this utopia. Often, merely by existing as an artist, one enters this utopia. I admire Gentileschi and how she painted the beheading of John—that contains everything! Today, there are still matriarchal cultures from which we can learn. I translate patriarchal religions and myths into a female form. For example, with my series “Shani/Saturn,” I have reflected on death in its female manifestation. What kind of relationship to death would we have today if we had developed concepts of female death goddesses instead of bloody, child-eating, angry, and unpredictable principles? Would there still be wars?

However, matriarchal energies must be entirely free of patriarchal settings. A Persephone ruled by others, forced to Hades, is not the creative energy needed for a true matriarchy. I want to abolish the religions associated with patriarchy. Every male god represents only humiliation for the feminine. Even when he seems to exalt it sometimes, it is always a top-down hierarchy. We no longer need anything outside ourselves that once gave old male societies support, direction, and law. We need an ethical, compassionate, pure consciousness that everything is interconnected and responsible. This is a feminine quality that only remains alive if even women mutilated by patriarchy hold no power. We must practice, evoke, and create the proper conditions for this alternative consciousness. Creation myths offer a symbolic framework that addresses archetypal origins and the collective unconscious, endowing my figures with a reconnecting dimension—a link to humanity’s prehistoric beginnings when women were the creators and nurturers, the honored goddesses whose power held the world together and who were revered and emulated.

By interweaving both themes, visual narratives arise that reflect identities, power relations, and societal constructions, while simultaneously opening space for subjective experiences and alternative realities. Thus, the figures become carriers of history, culture, and critical reflection alike.

6. You describe your work as a new form of Surrealism. How does this approach help you deal with fragmentation and overload in contemporary life?

We live in a hyper-connected present where technology radically transforms our perception. Information overlaps, images flood our senses, simultaneity replaces depth. The classical distinction between dream and reality has become obsolete—not because we dream, but because we are overwhelmed. There is no space left for dream worlds except in retreat. And we cannot afford that.

This is why I redefine Surrealism: not as a nostalgic stylistic quote, but as a contemporary necessity. My Surrealism is a critical reaction to technological overload, to the impossibility of penetrating one thing deeply. It is not escapism, but resistance against the devaluation of the inner world. For me, surreality means making the fractures and contradictions of the present visible—not through flight, but through confrontation.

I work with figurative, surreal image worlds that seduce and irritate at the same time. They carry a feminist stance that opposes the normalized view of body, power, and history. My Surrealism is hyperreal, open to knowledge, and resistant. It is an attempt to reclaim depth—not in retreat, but in setting out.

Marina’s work circles around stories that have shaped generations and the stories that still need rewriting. Through her collages and drawings, she examines how the feminine has been framed, silenced or distorted and how those narratives might look if rebuilt with care and clarity. What we learn from her journey is that image making can be a form of questioning, and that even in a fast and saturated world, slow craft can hold its ground. Her path shows how long-held memories, studies in theatre and psychology, and a lifelong habit of looking closely can come together to form a practice that encourages us to rethink what we have been taught to accept. Her work stays with us because it asks us to look again and consider what might change if we dared to imagine differently.

To learn more about Marina, click the following links to visit her profile.

Arts to Hearts Project is a global media, publishing, and education company for

Artists & Creatives. where an international audience will see your work of art patrons, collectors, gallerists, and fellow artists. Access exclusive publishing opportunities and over 1,000 resources to grow your career and connect with like-minded creatives worldwide. Click here to learn about our open calls.