Artists Who Had No Childhood Friends! Befriended Their Materials Instead | Larysa Bernhardt

👁 253 Views

At Arts to Hearts Project, we look for artists whose work carries the weight of something lived. Not performed. Not theorized. Lived. Artists who found their language not through formal training but through necessity because they needed to make sense of something that couldn’t be said any other way.

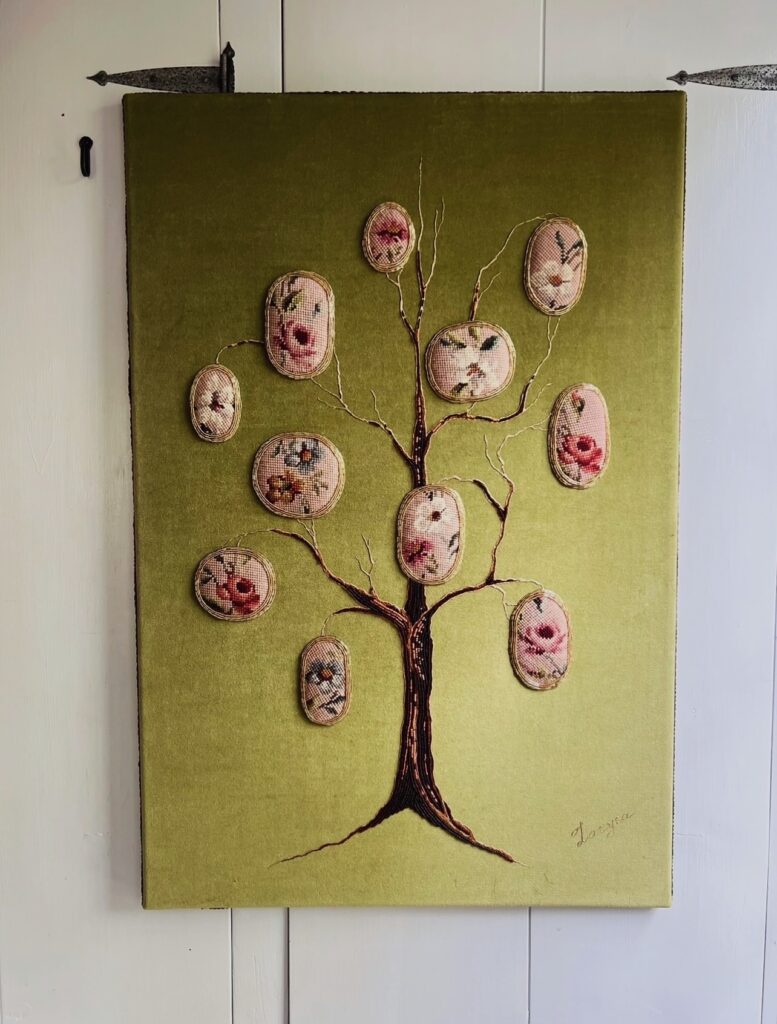

For our Best of the Art World series today, we’re beyond excited to present Larysa Bernhardt an artist who stopped us mid-scroll and made us lean closer to the screen, squinting at details, wondering how someone creates work this alive from materials most people would throw away.

We search through hundreds of portfolios every month. We see incredible technique. Stunning compositions. Work that deserves every bit of recognition it gets. But every once in a while, we find someone who makes us feel like we just discovered a secret. Like we stumbled onto something precious that not enough people know about yet. That’s exactly what happened when we found Larysa

Her textile sculptures are made entirely from survivors sun-bleached tapestries, needlepoints that unravelled because they were loved to death, beads that lost their sparkle a hundred years ago but gained mysteries instead. She only works with damaged materials. Pieces that didn’t survive their previous lives intact. And here’s what got us: she doesn’t treat that damage as something to hide or fix. She treats it as the whole point. The scars, the wear, the moth holes that’s where the story lives.

We couldn’t stop looking. How does someone develop an eye for this? How do you decide which damaged textile carries the right story? And more than anything how do you build something this cohesive, this intentional, from fragments that were already falling apart?

Before you hear from Larysa herself, you need to know where all this started.

Larysa was born in Ukraine. Her childhood split between two completely different worlds: city life with her parents’ museums, concerts, structure, schedules and countryside with her grandparents where there was no structure at all. She had to walk everywhere. She had chickens for friends. Actual chickens. Not a metaphor

And textiles were everywhere. Her mom taught her to sew and embroidery quiet, careful, refined. Her grandmother covered every surface in handmade rugs and tapestries with a philosophy of “everything goes, if not on the body, then on a wall.” Riotous. Fearless. Larysa says if she stood still long enough, the rugs would silently grow over her not threatening, but protective. Cocooning. Like they were keeping her safe. That image haunted us. Textiles as living things that could grow over you. Hold you. Protect you.

And here’s something that made us love her even more: Larysa employs all her senses to understand the world. She gets concerned looks from museum staff when she’s on the floor trying to smell paintings. When she’s allowed to touch textiles, you’ll see her with hands deep in the fibers, eyes rolled back, completely transported, trying to figure out how it makes her feel. She’s embarrassing in public. She knows it. She doesn’t care. Because that’s how she understands things through smell, touch, texture, memory.

She works primarily with velvet. Which is, objectively, one of the hardest materials to work with. You can’t transfer sketches onto it crushes the fibers. You can’t unpick stitches if you change your mind. She’s forced to stitch completely freehand. Be careful with every single choice. Allow room for mistakes because there’s no going back. She calls it being “in a relationship with her medium.” And just like any difficult love, it demands challenge and sacrifice.

Her process starts with a sketch. But she’s fully aware it’s going to change sometimes completely as she works. She used to fight that. Used to resist betraying the original idea. Now she knows it’s pointless. Her work evolves with her. She’s not the same person who drew that sketch twenty minutes ago. So why should the work stay frozen?

She collects fabrics from around the world, but she doesn’t buy anything just because it’s pretty. It has to earn its place in her heart and her studio, which isn’t very big. Some gorgeous pieces have been waiting decades because she still doesn’t feel “worthy” of altering them. She only uses pieces that didn’t survive their previous lives. If a textile isn’t damaged, if it still has too much life in it straight on the wall.

We chose Larysa for Best of the Art World because her work reminds us why we started this series in the first place: to spotlight artists who are doing something so specific, so personal, so unapologetically themselves that it cuts through all the noise. Artists who make you lean in closer. Who make you want to smell the work, touch it, understand it through every sense you have.

Now, let’s hear from Larysa in her own words.

Q1. Can you share your background and how growing up in Ukraine without formal art training shaped your early connection to textiles as a means of expression?

I was born and spent my formative years in Ukraine. My time was split between city (parents, school, museums, concerts, public transportation) and countryside where my paternal grandparents lived – no structure, no schedule, i had to walk to get anywhere, chickens for friends. Textiles were connective tissue between the two – with my mom’s quieter and more refined version of dressing and decorating (i learned everything i know about sewing and embroidering from her) to my grandmother’s “everything goes, if not on the body then on a wall” riotous approach. And not just the walls – the floors were covered also, handmade rugs everywhere. It felt that if I was still long enough the rugs and tapestries would silently grow over me – not in a threatening but in a protective, cocooning way.

Q2. You describe the textiles you collect as arriving with scents coffee, spices, old books, lavender that hint at their histories. How do these sensory histories influence the emotional life of the work before you even begin stitching?

I didn’t realize it until recently but i employ all my senses to understand the world. I get concerned looks from museum staff when i am craning over lines on a floor trying to smell the painting. Texture is important also, and when i am allowed to touch you will see me with my hands deep into the fibers, my eyes rolled deep into my head trying to figure out how it makes me feel or what it reminds me of. I am embarrassing in public, no wonder i only had chickens for friends.

Q3. Velvet is notoriously difficult to work with, yet you embrace its challenges. How does that “love/hate” relationship with materials inform the emotional tenor of your pieces?

Don’t make a mistake,

I love velvet. And just like any difficult love mine comes with challenge and sacrifice.

Larysa Bernhardt

From early on I realized I can’t transfer my sketches on velvet. It crushes delicate fibres and markings cannot be washed off if i had a change of heart or the better idea came along and it happens every time! I also have to avoid unpicking stitches if i didn’t like my choice of colours or design – unlike linen or any other sturdier fabric, velvet is unforgiving, perhaps like all things delicate and fragile it worth an extra effort. I am forced to stitch my designs freehand, be extremely careful with my choices, and allow room for mistakes and misunderstanding. I am in a relationship with my medium.

Q4. Your process often begins with a sketch but evolves organically over time. What do you look for in the transition from the conceptual sketch to the materialised sculpture?

I get my ideas in a process of working. I start with a sketch but i am fully aware that things are going to change, sometimes drastically, as i am getting deeper into the piece. I used to resist betraying original idea but now i know – this is battle not worth fighting. My work evolves with me, and i am not the same person that drew that sketch twenty minutes ago. So i let it change with me.

Q5. You collect fabrics from around the world, some with visible damage from time and moths. How do you decide which textiles to bring into your work and what stories they might carry or continue?

I let my materials speak to me. I don’t buy anything that is simply “pretty”. It has to earn its place in my heart – and in my studio, which is not very big! I rarely know what piece of textile i will choose to work with next. Some absolutely gorgeous pieces were waiting for decades, and i still don’t feel myself “worthy” of altering them in any way. Sometimes i wonder how idea and materials come together, it’s such an intuitive thing, like gossamer threads appear in my head, connecting images in my mind to pieces of old tapestries or remnants of needlepoints. Did i mention that i only use pieces that didn’t survive previous lives? beads that were brilliant hundred years ago but lost much of their sparkle – and gained mysteries instead. Needlepoints that unraveled because they were loved to death, or sun bleached tapestries. But if the piece is not damaged and still has a lot of life in it – it goes straight on a wall! Thank you grandma.

Q6. As your work reaches wider audiences, have you felt pressure internal or external to clarify, expand, or alter your visual language?

Yes! and i squashed it. Now i let my work speak for itself. What i see is not what you see, and its the beauty – and mystery – of art.

Wrapping this conversation with Larysa, I keep coming back to something she said that I almost missed the first time: “I am in a relationship with my medium.”

Most artists would never use that word. Relationship. They’d say they “work with” materials or “use” techniques. But Larysa said relationship. And the more I think about it, the more I realize that single word explains everything about why her work feels so different. Because relationships require listening. They require compromise. They require you to show up as yourself, not as who you think you should be. And they change you whether you want them to or not.

Larysa can’t control velvet the way she could control linen or cotton. She can’t transfer her sketches, can’t unpick mistakes, can’t force it to cooperate. Velvet demands she work freehand, be careful with every choice, allow room for error. Most artists would call those limitations. She calls it love. A difficult love, yes. But love nonetheless.

What fascinates me most is how this philosophy extends to everything in her practice. She starts with sketches but lets them change completely. She used to resist that—felt like she was betraying the original idea. Now she knows it’s pointless to fight. She’s not the same person who drew that sketch twenty minutes ago. Why should the work stay frozen?

Think about what that means. Most of us spend enormous energy trying to maintain consistency. Trying to stick to the plan. Trying to become the person we said we’d be. Larysa just… lets herself change. And lets the work change with her. That takes a kind of trust I’m not sure most artists ever develop.

What also stayed with me was her talking about employing all her senses to understand the world. Getting concerned looks from museum staff when she’s on the floor trying to smell paintings. Hands deep in fibers, eyes rolled back, completely transported. She knows she’s embarrassing in public. She doesn’t care.

Because here’s what she understands that most of us forget: you can’t truly know something by looking at it from a safe distance. You have to get close. You have to touch it, smell it, feel it, let it affect you. You have to be willing to look ridiculous. To be vulnerable. To engage fully even when it’s uncomfortable.

And maybe that’s exactly why her work resonates the way it does. She’s not protecting herself. She’s not maintaining professional distance. She’s all in—with the materials, with the process, with the risk of letting things change, with the embarrassment of being fully herself in public.

And she only works with materials that earn their place in her heart, which means some gorgeous pieces sit untouched for decades until she feels worthy of them. That kind of patience, that kind of respect for materials, that willingness to wait until the relationship is right that’s not something you can teach. That’s something you learn by having chickens for friends and standing still long enough to let tapestries grow over you.

Follow Larysa Bernhardt through the links below to explore her work and process. What you see may be different and that’s the point.