Why you should Keep Making Art Even If You Think It’s Not Good Enough I Elizabeth Haines

👁 27 Views

At Arts to Hearts Project, we spend a lot of time thinking about what makes a landscape painting actually work. Not technically anyone can learn that. But emotionally. What makes you look at a scene and feel like you’ve been there, even if you haven’t?

When we were putting together our 101 Artbook: Landscape Edition, we wanted artists who understood that landscape isn’t just about pretty views. It’s about memory. Mood. The feeling of standing somewhere and letting a place settle into you.

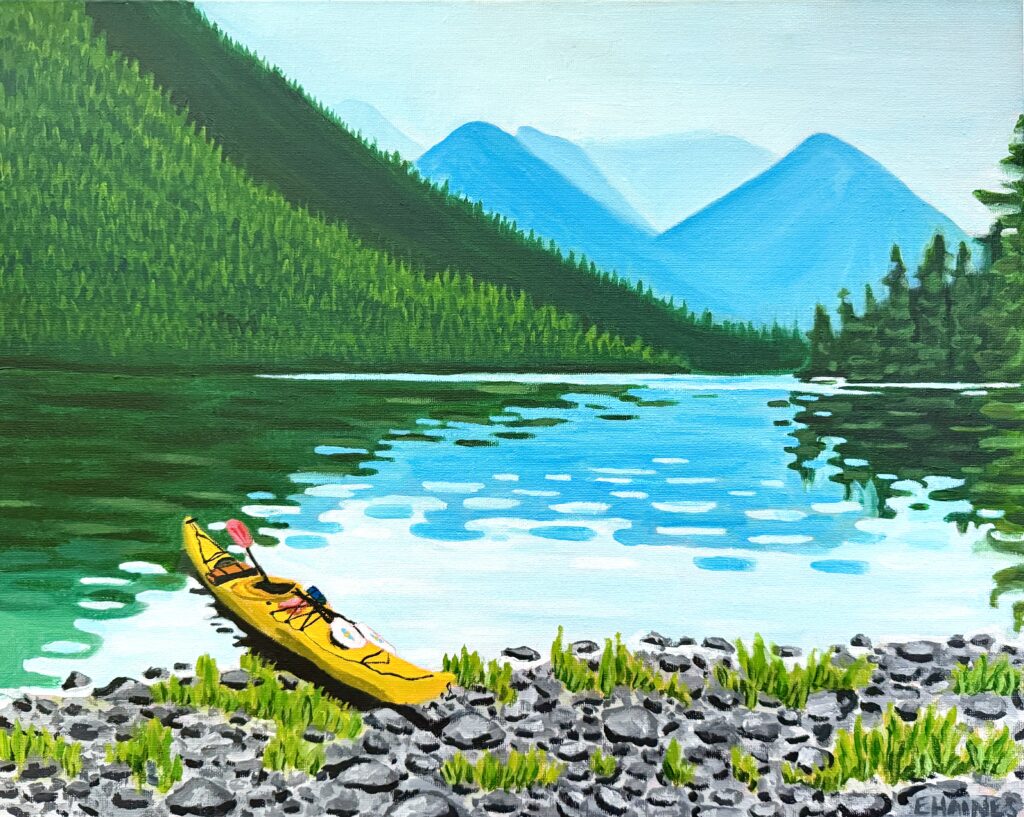

Elizabeth Haines gets that completely. Her paintings of the Sunshine Coast don’t try to impress you. They invite you in quietly. Soft light on water. Misty mornings. The kind of stillness you only find in remote places where life hasn’t been sped up yet. Looking at her work felt like remembering somewhere I’d never actually been.

We selected Elizabeth for this edition because her landscapes do what the best ones always do they’re not about the place. They’re about the feeling of being there.

Here’s what makes Elizabeth’s practice unusual. She’s an elementary school teacher in Madeira Park, a remote community on the west coast of British Columbia. And she only paints seriously for two months a year July and August, when school’s out. The rest of the year? She teaches. Focuses on her students. Steps away from the easel to protect her mental health.

Most artists would panic at that rhythm. But Elizabeth’s made peace with it. September through June, the paintbrush stays down. But her mind never stops. She’s taking reference photos. Collecting supplies. Thinking about what she’ll paint when summer comes. So when July hits, she’s ready to dive in completely.

And even during teaching months, she’s still creating—just differently. Beading. Embroidery. Digital art. Projects with her students. She’s figured out that creativity doesn’t have to look the same all year to be real.

Growing up on the Sunshine Coast surrounded by ocean and forests shaped how she sees the world. She studied education at Trinity Western University with a focus on arts education, which means she’s spent years teaching kids to express themselves visually. That’s fed back into her own work in unexpected ways.

Teaching sharpened her understanding of how images communicate. How color creates mood. How composition tells stories without words. She thinks about clarity now. Emotional accessibility. How a painting connects with someone who isn’t trained to “read” art.

She intentionally looks for quiet when choosing subjects. Living somewhere remote and slow-paced, she paints that energy moments when nothing dramatic is happening, but everything feels important. Soft tones. Moody skies. Light moving across water. The atmosphere of a place rather than just its appearance.

One moment that shifted everything was visiting Roy Henry Vickers’ gallery in Tofino. His work made something click: art as storytelling, as personal experience. Not just depicting a place, but sharing what it felt like to be there.

And here’s why this conversation matters: Elizabeth said something every artist needs to hear: “You might feel like your art is not good enough, but even if you feel that way, keep creating. If you feel like the world doesn’t want to see your art, show it anyway. If art makes you happy, keep on creating no matter what.”

That’s not coming from someone who’s never doubted. That’s coming from someone who knows exactly what that doubt feels like and has decided to make the work anyway.

Let’s hear from Elizabeth about how teaching shaped her visual language, why she seeks stillness in her subjects, and what it means to create on a seasonal rhythm.

Q1. Can you share your background, where you grew up, your early training in art, and when painting became your defining pursuit?

I grew up on the Sunshine Coast of British Columbia, Canada, surrounded by ocean, forests, and a strong creative community. I attended Trinity Western University, where I earned a degree in education with a specialization in arts education. I now teach elementary school in Madeira Park. One of the joys of teaching is having two months off in the summer, time I devote to painting and selling my artwork at local markets each summer season.

Q2. You mentioned that you thrive in the summer months and spend other seasons teaching, can you describe how the rhythm of the year shapes your creative output?

From September to June, I find myself very committed to my career as a teacher and on the weekend I prioritize my mental health and self care. For me, that means putting the paint brush down, but it never stops me from thinking about my art. All fall, winter and spring I’m thinking of my next painting, taking reference photos and collecting art supplies so by the time July comes, I’m ready to completely indulge in painting. Even though I put my paint brush aside for those times, I still find myself creating in other ways like beading, embroidery, digital art and of course being creative with my students.

Q3. Your work often evokes a sense of quiet presence, is cultivating stillness something you aim for intentionally in your studio practice?

I think I intentionally seek out quiet and stillness when looking for the next thing to paint. I live in a remote community on the west coast of Canada, and things often are slow paced. I definitely like to capture that.

Q4. How does the natural environment light shifts, weather, time of day affect your choices in colour, composition, and mood?

Because I paint mostly in the summer, I find that I have brighter tones in most of my painting. But I do have paintings that I’ve done in the fall and winters that have softer tones to them and a more moody energy, for example: dark skies and misty atmospheres.

Q5. How did your experiences as a teacher help you form a vocabulary of visual expression and narrative in your own art?

Teaching has helped me develop a clear visual language rooted in storytelling. Guiding students to express ideas through art has strengthened my understanding of composition, colour, and visual cues as tools for communication. This experience influences my own work by encouraging clarity, emotional accessibility, and narrative depth.

Q6. Are there particular artists, writers, or moments in your life that have deeply shaped how you think about creativity and seeing the world?

Roy Henry Vickers is definitely an artist and story teller that I admire and inspires me. When I saw his gallery in Tofino, I definitely had an “ah-ha” moment as creating art as storytelling and art as personal experience and adventure.

Q7. In your creative process, is there a moment when you feel most in flow right at the beginning, in the middle, or near completion?

Definitely at the beginning of a project I find I am in the best flow. When I feel like I’m almost done, it takes me sometimes days to get the last details done. I often need to step away and have fresh eyes in order to finish it.

Q8. What advice would you give to emerging artists today about developing a voice that is both life-rich and visually distinct?

You might feel like your art is not good enough, but even if you feel that way, keep creating. If you feel like the world doesn’t want to see your art, show it anyway. If art makes you happy, keep on creating no matter what!

Talking with Elizabeth left me thinking about something I don’t consider enough: what if the pressure to create constantly is actually getting in the way?

She paints two months a year. Two. The rest of the time, she’s teaching, living, thinking—but not painting. Most artists would spiral at that. The fear that stepping away means losing something. That if you’re not producing, you’re not real.

But Elizabeth’s proven that’s not true. When July comes, she’s not rusty. She’s ready. Because creativity didn’t stop during those ten months. It just moved underground, collecting and building. Maybe we’ve got it backward. Maybe constantly producing is what burns people out. Maybe the artists who last are the ones who’ve figured out how to let creativity breathe.

What keeps coming back to me is how deliberately she seeks stillness. Not just in her schedule, but in what she paints. Living somewhere remote where life moves slowly, she’s capturing moments when nothing urgent is happening but everything feels significant.

We’re trained to think art needs drama. Big statements. Bold gestures. Elizabeth’s paintings do the opposite. They ask you to slow down. To notice light on water. To feel a place instead of just looking at it.

And honestly? That feels more necessary than ever. But the thing that’s stayed with me most is what she said about doubt.

“You might feel like your art is not good enough, but even if you feel that way, keep creating.” That’s not abstract advice. That’s lived experience. That’s someone who’s felt that doubt and decided to make the work anyway. Not because she’s convinced it’s brilliant. Because making it matters to her.

How many people stop before they start because they’ve decided their work isn’t good enough? How many ideas die because the voice says “why bother?” Elizabeth’s saying: do it anyway. Even when you don’t believe in it. Even when you’re convinced nobody cares. If it makes you happy, that’s enough.

Follow Elizabeth Haines through the links below and witness someone who paints with the rhythm of seasons, captures moments most people rush past, and keeps creating even when doubt says it’s not good enough.