Rachel Romano Shows You Why You Don’t Need a Bigger Studio

👁 41 Views

At Arts to Hearts Project, we’ve always believed that if you really want to understand someone’s art, you need to see where they make it. Not just the finished work hanging on a wall somewhere, but the actual space where it happens. The room, the corner, the makeshift setup. Because studios aren’t one thing. They can be industrial lofts with soaring ceilings, or a garage you cleared out on a weekend, or honestly just a table in your kitchen that you’ve claimed as yours. What we’ve realized after years of doing this is pretty simple: the space itself doesn’t matter nearly as much as what happens when someone shows up there and does the work.

We’re seven volumes into our Studio Visit Book series now, and we’ve seen just about every kind of setup you can imagine. Big dramatic warehouse spaces. Tiny corners carved out with determination. Immaculate, organized rooms. Beautiful, chaotic messes. And honestly? Every single one taught us something different about what it actually takes to keep making work, year after year, through everything life throws at you.

This time around, we asked artists to think about “Home.” Not in some vague, poetic way, but really what does home mean to you? Where do you feel like yourself? What space holds you when things get hard? The answers we got back were all over the place, and that’s what made them so good. But one thing kept coming up: for a lot of artists, the studio becomes home. Not because it’s comfortable or beautiful, but because it’s the place where they can finally be honest.

Going through all the submissions, Rachel Romano’s story stopped us cold. Not because it was flashy or dramatic actually, it was the opposite. There was just something about what she’d figured out that felt quietly radical.

Here’s the thing: Rachel painted in industrial buildings for years. The kind of spaces artists fantasize about. High ceilings, big walls, tons of light. Other artists in the building who got it, who understood what it’s like to show up every day and make work even when it’s hard. That community isn’t something you walk away from easily. But life shifted, the way it does, and Rachel had to make a choice she didn’t see coming. She moved her studio home.

Now, you’d think that’s a downgrade, right? Trading the dream space for something smaller, more cramped, tangled up with laundry and dishes and all the noise of regular life. But what Rachel discovered kind of turns that whole assumption upside down. Because when her studio came home, something happened that had nothing to do with square footage or aesthetics. It had to do with access. With freedom. With being able to work in ways those big impressive spaces never actually allowed.

Before we get into Rachel’s studio, let us tell you what pulled us in. Rachel paints people, but not the way you’d expect. She’s cut something out of her process that most figurative painters would call essential. And that choice? It’s completely changed not just how her work looks, but where it comes from. Her dad was a writer, a poet. He used to take her to the Met when she was a kid, and those trips did something to her planted something that’s still growing in every painting she makes. There’s a relationship between words and images in her work that doesn’t show up in most painters’ studios.

Walk into her space and you’ll see something else that breaks the rules. She’s got multiple paintings up at once. Big ones. All at different stages. Some almost done, some just starting. And it’s not chaos or indecision it’s intentional. She’s protecting something by working this way. Because she’s learned that focusing on just one painting does something dangerous. It makes the work precious. And when work gets precious, you stop taking risks.

Here’s where it gets weird, though. Rachel talks about her paintings like they have a relationship with each other. Not in some airy, mystical way she means it practically. Things happen between those canvases when she’s not even in the room. Problems solve themselves. Connections appear. It’s like they’re figuring stuff out together, and she’s learned to trust that even when it doesn’t make total sense.

And then there’s the light thing. Rachel’s particular about light in a way that goes deeper than preference. She’s figured out that certain kinds of light even the “good” kinds, the ones painters are supposed to want actually lie to her. They make her work dishonest. Once she understood that, everything about where and how she could paint changed.

So what does her home studio look like now? It’s smaller than what she had. Less storage. No artists down the hall to grab coffee with when things aren’t working. But there’s something else she got in exchange, something that has to do with time and spontaneity and being able to respond when creativity shows up at inconvenient hours. She’s got an outdoor space now, attached to the studio, where she can step out and breathe when she needs to. And when people visit, something’s different. They don’t just see the work anymore they see her.

Rachel’s story makes you ask questions you maybe don’t ask enough. Like: what if the studio you think you need isn’t actually helping your work? What if being able to access your space at 3 a.m. matters more than having high ceilings? What if your paintings are smarter than you are, and part of your job is just giving them room to figure things out? What if bringing your studio home isn’t a step back it’s just a different kind of commitment?

Now let’s hear from Rachel about what actually happened when her studio moved home, what she’s learned about light and truth, why she works the way she does, and what those paintings are doing when she’s not looking.

I began my conversation with Rachel by asking about her studio transition she’d spent years painting in an old industrial building in Coatesville, PA, but recently moved her studio home. I was curious how that shift in space changed her daily work rhythm.

So, for many years I had my studio in old industrial buildings. I have always chosen an eastern or southern light exposure. Northern light is too cool for me. I paint warm, and cool light is deceptive, and I ending up having paintings that are over saturated in color and too hot. Having such bright light does have to be diffused some parts of the day, either naturally with tree cover, or with sheers on the windows. In the end I am a sunshine girl, my moods require the sunlight. The pros of having an industrial space are usually high ceilings, large floor/wall areas, and if it is an artist’s building, the camaraderie can be a huge boost to your art mentally. Regarding the space itself, there are no limitations (maybe doorways) on the size, and amount of work you create. The possibilities are endless. Having other artists in the building is a bonus, when you are stuck, feeling alone, or wanting to have an art party, offering you moments to share in the tribulations of being an artist and art making. Recently, due to a personal situation I have had to move my studio home. It’s not quite as large as my industrial space, but provides me with other benefits. Having had the rhythm of going to another location, helped solidify my commitment to a practice, and there were no home distractions. That said, I do not miss getting in a car everyday, and now having the ability during sleepless nights to pad down to the studio at 3 am, is a creativity enhancer. I have learned to be selfish, and turn off the home noise. I care less about daily chores, it has simplified my art life in many ways. I can create 24/7, if my body allows. I have a beautiful outside space attached to the studio, which gives me the ability to take the noise away, and clear my head. When I have studio visits, I may have had the dramatic effect of an industrial space, but alternatively people now connect with me on a more personal level. Having other artists in the building is a bonus when you are stuck, feeling alone, or wanting to have an art party. These times offer you moments to share in the trials and tribulations of being an artist and art making.

Walking through her space, I noticed something striking many large works and smaller studies coexisting on the walls, all at different stages. I asked her how she decides when to return to a painting versus letting it sit and breathe.

My works are spread out along a long wall, which gives me visual space to contemplate what is happening with each, and the dialogue between them. I will move one aside If I need to let it percolate. I will keep painting or drawing on something, so that the creative flow is not disrupted. I am always thinking about multiple works at once. They are familiar to one another, and to me, and there is a relationship to one another even if the topic, or colors seems disparate. There is no real design in intervention, it comes more from an emotional, feeling place, and just knowing the time is right to get back to it.

Rachel’s described her early encounters with art traveling with her father to the Metropolitan Museum of Art as a child as foundational to her sense of storytelling. I wanted to understand how that early memory surfaces in her work now.

My father being a writer/poet gave me a world of words and imagery. The two always having to co-exist with each other. The sojourns with him, beginning at age 7, were about discovering the infinite possibilities, mystery, and magic of a creative life. There was a child’s wonder unfolding, peeling back like petals on a flower, during these adventures. That feeling of wonderment, and endless possibilities is there each time I start a new work. Words come first to me, then imagery, that was a gift from my father being a writer. I think words are freeing, and if imagery is too solidified at the start, it restrains me. I want to remember and feel that child’s wonder of discovering and making art.

One thing that distinguishes Rachel’s process is that she paints from memory and imagination rather than directly from models. I asked her what changes visually or emotionally when memory guides the image instead of live observation.

Painting from the inside out, as I describe it, is an emotional place. Painting from a model becomes a technical place for me. I am not discounting the value in learning to see, and studying from a model. When laying down imagery I can’t have the distraction of looking at a model. I become obsessed with getting it right rather than letting it just flow, and I can be too much of a perfectionist. I need to feel what I am doing, moving over the body in my mind, in a kinetic way. I am not looking for perfection in the structure, but an overall expression to the story. When I begin a painting there are no restrictions other than what I can imagine. Reality of life, and everyday things fall away into an imagined place. Rather than being in their true context, placement becomes a why not/what if implementation. I look upon the composition as a fantastical window into another world, letting my imagination, not reality guide me in the storytelling. Some bases of real truth may emerge, but ultimately, it’s the weaving of figures and elements together that represents my inner vision.

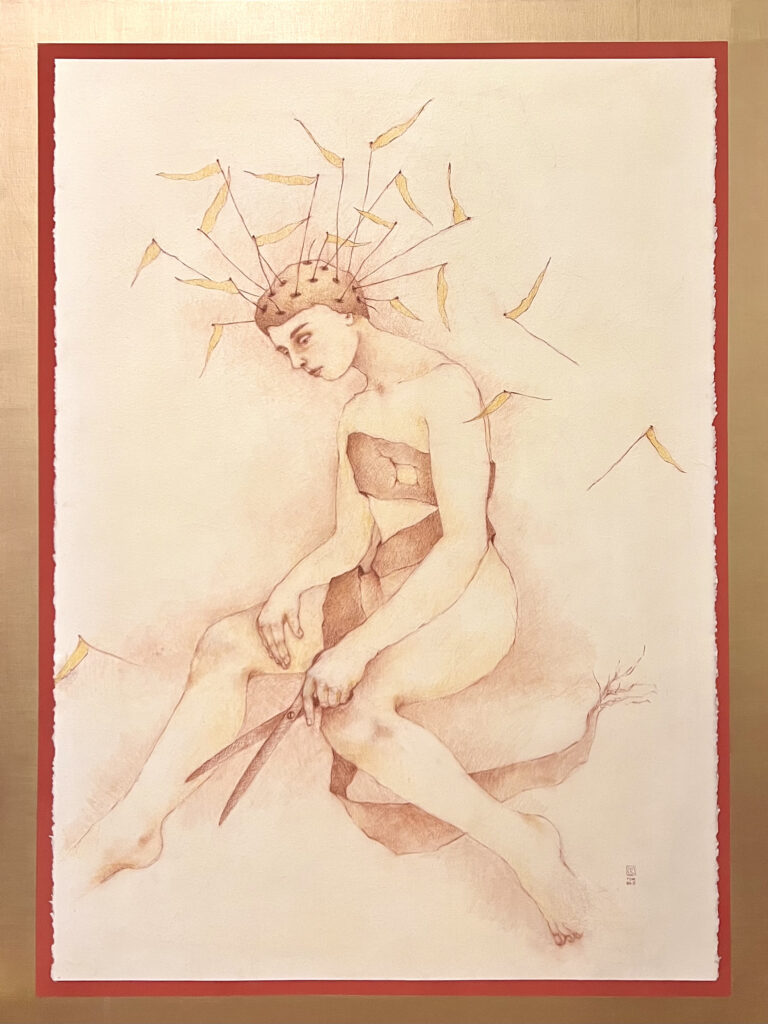

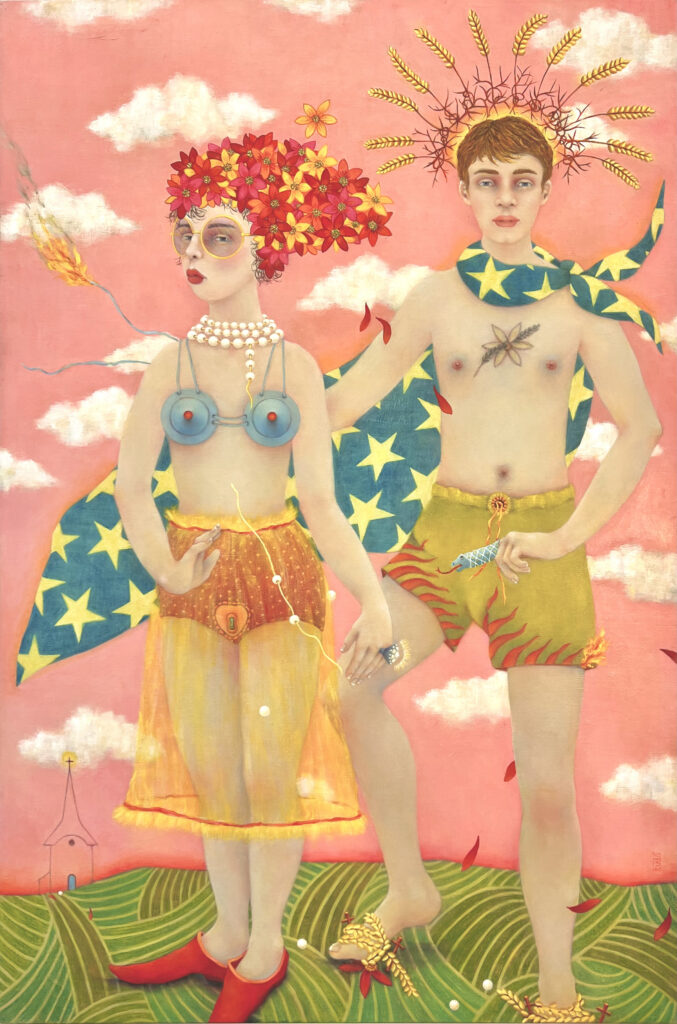

Looking at pieces like In A Garden We Plant and Wrestling Crocodiles, I was struck by the dynamic between figures and environment, narrative and abstraction. I asked Rachel how she balances storytelling with ambiguity in these surfaces.

This is an interesting observation. So many paintings I admire, are full of detail, i.e. Bruegel, Bosch, Carrington, Spencer’s work, etc. And contemporary artists such Heffernan, Paone, and so many more. For me I find I need resting spaces in my paintings, much like Romaine Brooks work. Areas of unknowing, taking you away from the drama of the moment of the central figure(s). Many times I think “fill the canvas more,” but instinctively come back to simplifying my story. I pay great attention to the flow of the imagery, and if my eye keeps moving around the story. I love the juxtaposition of abstract vs. the direct realism approach to the figure, and objects. It creates a tension, and otherworldliness. I want there to be mystery in the work.

Rachel’s mentioned she works on several paintings at once to keep them from becoming too precious. I was curious how this simultaneous progression changes the way she mentally enters and exits the studio.

Not being focused entirely on one painting at a time allows me to let go. To not sweat the small stuff, or even challenges. I become fearless. If something is not working, I will walk away for a bit, or wipe it out. I can come and go from the studio without worrying what to do next. There are enough paintings on the wall to keep me in the painting mode and occupied. Creating endless possibilities for me.

I asked her how long works usually stay unresolved in her studio, and how she lives alongside that uncertainty day after day.

A painting usually takes a couple of months to complete, So when I am working on several at once, that can represent 6 months or more of work. I don’t find uncertainty in this process. it s more of a birthing process, going through the growth and changes, and adjusting to those changes that come along. Having numerous works in progress allows uncertainty to fall away. It s kind of like having many children, when there is a dilemma with one, you still have others to deal with. It’s invigorating, and exciting. I will say that there are times, maybe 2/3 of the way through the process that I have a hump to get over, and it’s just perseverance that gets you through. The rest lies in the beauty, and of the flow of creation.

One thing I’ve always been curious about with artists who work on multiple pieces simultaneously: do unfinished works ever influence each other simply by sharing the same space? Can one painting unlock a solution for another?

Absolutely! There is an invisible thread connecting them, and sometimes I think a murmur going on between them. They are alive with possibilities, and only my imagination can present limitations. When working from one to the other, the connection between my hand and thought carries throughout. Many times I will be working on one and an aha moment hits me with a resolution for another. It’s a doing by feeling process. Staying open to the feeling is imperative.

After years of daily studio presence, I wanted to know what the studio has taught Rachel that no external feedback ever could.

Be fearless. Even in the worst of creative situations, frustration, errors, damage, etc. there is always a way through. It may not have been what you had in mind, but letting go of expectations can lead you to find another type of resolution, or beauty, that you may not have allowed yourself to do otherwise.

Be true to yourself. Find the joy, the childlike bliss in what you are looking to create.

For my final question, I asked Rachel what advice she’d give to artists trying to balance emotional depth with strong structure in their work.

This so is personal. I think you have to follow who your are instinctively, and in you heart. This doesn’t mean you can’t experiment, or change things up. There is no right way or wrong of creating art. Or thinking you should be a realist, abstract, surreal painter, just because of other’s expectations. I think it’s not so much about the structure, as it is about the emotion. The greatest paintings, from Rothko to Michelangelo send you to a visceral place of feeling. So connect with what makes your heart sing. Look at art that does this for you, and dive in deep as to why. Is it the color, the figures, the landscape that brings you to a place of self discovery in who you are as a painter? This can be challenging in these times. On the one hand there so, so many artists to investigate, social media has made the possibilities endless. On the one hand there are so, so many artists to investigate, social media has made the possibilities endless.

Talking to Rachel left us thinking about something we don’t talk about enough: the myth of the perfect studio. We’ve been conditioned to believe that serious artists need certain things space, separation, the right kind of light, maybe even other artists nearby to validate the work. And sure, those things can help. But Rachel’s story cuts right through that assumption and asks a harder question: what if what you actually need has nothing to do with what looks impressive?

Because here’s what struck us most. Rachel didn’t move her studio home because she wanted to. She did it because life demanded it, and she made it work. And in making it work, she discovered something most of us spend years avoiding sometimes the thing that looks like a compromise is actually the thing that sets you free. Losing the big industrial space meant losing drama, losing scale, losing that built-in community of other artists who got it. But it also meant gaining something those spaces could never offer the ability to walk downstairs at 3 a.m. and paint. No commute. No transition. Just immediate access to the work when it called.

What Rachel’s figured out is that home isn’t about the architecture. It’s not about square footage or exposed brick or whether your space looks like an “artist’s studio” when people visit. Home is wherever you’ve learned to protect your practice from the noise of everything else. And that’s harder when the studio lives inside your actual home, not easier. It requires a kind of selfishness that doesn’t come naturally to most people—the ability to turn off the dishes, ignore the laundry, let daily life fall away because the work on the wall matters more.

We keep thinking about what she said about her paintings talking to each other. That invisible thread connecting them. The way solutions emerge not through effort but through proximity, through letting multiple works breathe in the same space over months. It challenges this idea that focus means singular attention, that real commitment looks like obsessing over one piece until it’s perfect. Rachels learned that preciousness kills work. That fear of ruining something keeps you from letting it become what it needs to be. So, she works on six things at once, and they help each other, and somehow that mess of unfinished work creates more clarity than laser focus ever could.

And then there’s the whole thing about memory versus observation. She refuses to paint from models because it pulls her into a technical place when what she needs is an emotional one. She paints from the inside out, letting memory and imagination guide her instead of trying to capture what’s literally in front of her eyes. That takes a specific kind of trust—trust that what you remember, what you feel, what you imagine is more true than what you can see. And honestly, looking at her work, you can feel that difference. There’s a quality to it that doesn’t come from accuracy. It comes from somewhere deeper.

Rachel’s studio might not look like the dream anymore, but it functions like something better a space where she’s learned to be fearless, to let go, to trust that even when things fall apart, there’s always a way through. Moving home forced her to figure out what actually mattered about her practice, and what she discovered was pretty simple: it’s not the space. It’s the showing up. It’s the protecting. It’s the willingness to be selfish with your time because the work demands it.

Her story reminds us that home isn’t something you find or build once and then it’s done. It’s something you keep choosing, keep protecting, keep refining as life changes around you. Sometimes it’s a big industrial building with other artists down the hall. Sometimes it’s a smaller room in your house where you can paint at 3 a.m. and step outside when you need air. Both can be home. Neither is more legitimate than the other. What matters is whether the space lets you do the work honestly.

To see more of Rachel’s work and follow her journey, connect with her through the links below.