Think You Need To Quit Your Job To Be A Real Artist? She Believes Otherwise

👁 276 Views

We’ve been selecting artists for Best of the Art World long enough to recognize when someone has figured out something most people believe is impossible. Not through compromise. Not through sacrifice. Through genuine, equal love for two worlds everyone says can’t coexist.

That’s what stopped us about Geethu Chandramohan. She’s an aerospace systems engineer. She paints. She teaches thousands globally. She’s a mother. And she refuses to choose between any of it not because she’s “balancing” or “juggling,” but because she genuinely loves all of it and designed a life where each role feeds the others.

We reached out to Geethu because her practice dismantles the tired narrative that serious artists must quit their day jobs to prove commitment. The story goes: passion requires suffering, stability kills creativity, you can’t serve two masters.

Geethu looked at that story and said no. Not out of defiance, but out of clarity about what actually sustains a decades-long creative practice, and it’s not escape plans or burnout chasing freedom. It’s passion for the work itself.

She grew up living in two worlds. Loved science, was fascinated by aircrafts and space, painted in her free time, joined children’s art competitions. For a long time, she didn’t realize she could pursue both professionally. When she did, it became her life-changing moment. Engineering taught her to see structure beneath complexity, how layers interact, how fragile things become strong through intentional design.

Art gave her freedom to explore emotion, intuition, imperfection without justifying them. These worlds don’t oppose each other in her mind they inform each other quietly, constantly.

After her son was born, she made one decision that changed everything: she works a four-day week in aerospace, and Fridays became sacred studio days. Time stopped being something she hoped to find and became something she designs every week. Constraints became gifts teaching her to work with clarity instead of chaos.

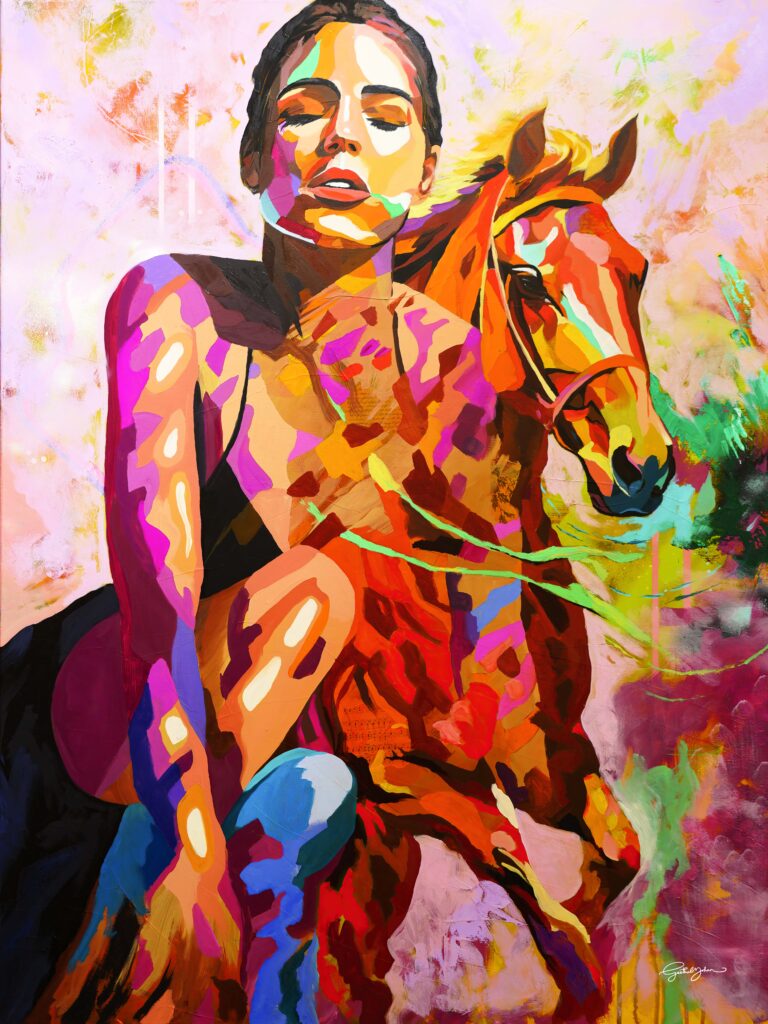

She paints women not idealized versions, but the strength most people misunderstand. The kind that shows up as resilience, gentleness, patience, the ability to hold many things at once. Joy that lives quietly inside someone. Fire that exists beneath softness.

Her mixed media work honors that inner world, recognizing depth and dignity already present but often unnoticed.

What’s remarkable is how systems thinking from engineering shows up in her art practice. She keeps 25 to 30 paintings in progress at once. She’s never experienced artist’s block not because she’s never stuck, but because when one piece needs rest, another moves forward. Momentum shifts instead of stopping. It’s not a straight line. It’s a living system.

Now, let’s hear from Geethu herself about what it means to live in two worlds since childhood, about the decision she made after becoming a mother, and why she’ll never choose between who she is.

Q1. Can you share a bit about your background, how your journey as an aerospace engineer led you toward art, and in what ways these two seemingly different worlds continue to inform and inspire each other?

I’ve always lived in two worlds, even when I was a child. I loved science and was fascinated by aircrafts and space and at the same time painted during my free time, joined children’s art competitions and always enjoyed sketching and painting. I pursued my passion as an aerospace engineer (I can’t even imagine being anything else!) and currently work as an aerospace systems engineer, a field that is rooted in precision, systems thinking, and get the opportunity to make things that fly. At the same time, art was always there with me, as a way of processing the world, of slowing down, of listening to what couldn’t be solved or optimised. For a long time, I didn’t realise that I could pursue both professionally, but when I did, that was my life changing moment ever. Engineering taught me how to see structure beneath complexity, how layers interact, how something fragile can still be incredibly strong when designed with intention. Art gives me the freedom to explore emotion, intuition, and imperfection, without needing to justify them. When I paint, I’m constantly thinking in layers, systems, balance, and flow, all ideas that come directly from engineering, but expressed through texture, colour, and the human form instead of equations. And interestingly, art feeds back into my engineering life too, it keeps me curious, observant, and deeply aware that not everything meaningful can be reduced to data. I don’t see these worlds as opposites anymore. They inform each other quietly and constantly. One keeps me grounded in logic and responsibility, the other keeps me connected to feeling, imagination, and humanity. Together, they’ve shaped how I think, how I create, and how I move through the world, with both clarity and softness existing side by side.

Q2 . Your work is described as bold, expressive mixed-media pieces, and you speak of capturing “the strength of a woman, the joy tucked inside stillness, the fire that lives beneath softness.” What motivated this focus of your creative voice?

This focus grew very organically, without me realising it at all. I think this comes from observing women’s emotions and feelings closely, in real life and in myself. So much of strength is misunderstood as hardness or noise, when in reality it often shows up as resilience, gentleness, patience, and an ability to hold many things at once. I’m deeply interested in that contradiction, the way softness and power coexist, the way joy can live quietly inside someone without needing to be displayed. Mixed media allows me to explore this visually, through layers, textures, and marks that suggest history, complexity, and emotion beneath the surface. My creative voice is really about honouring that inner world. Painting becomes a way of saying that strength doesn’t always look the way we expect it to, and that there is something really powerful about stillness, presence, and self containment. It’s not about idealising women, but about recognising the depth and dignity that already exists, often unnoticed, within them.

Q3. Your paintings began in watercolour and then transitioned into richer mixed media with texture and layers. What prompted that evolution and how did you know you needed a new medium?

Watercolour was my first love in painting. I loved its sensitivity, the way it responds to the smallest shift in touch or amount of water, and how it asks you to trust the process rather than control it. I had always wanted to paint portraits, that feeling was always there. But whenever I tried them in watercolour, I didn’t enjoy the process. Technically they were fine, but emotionally they never gave me that spark, that sense of excitement or connection I was looking for. I kept feeling like I was forcing the medium to do something it didn’t want to do, and the results reflected that. Everything shifted when I discovered mixed media. Suddenly, the possibilities with it felt endless. I wasn’t confined to transparency or delicacy anymore, I could build, scrape back, add texture, layer emotion, and let the surface itself become part of the story. That freedom changed how I approached faces, especially women’s faces. Mixed media allowed me to express depth, strength, softness, and complexity all at once, in a way watercolour portraits never allowed me to. Once I started working this way, I knew there was no going back. It wasn’t just a change in medium, it felt like I had finally found the language that matched what I had been wanting to say all along.

Q4. You’re working while balancing a full-time career and motherhood. How has motherhood and your full-time career shaped your art practice in terms of time, inspiration, constraints?

Motherhood and a full-time career have shaped my art practice very deliberately. Time is no longer something I hope to find, it’s something I design every week. I work a four-day week in aerospace engineering, and Fridays are protected as my studio days. That one decision after my son was born changed everything for me. It gave my art consistency, respect, and a clear place in my life rather than something squeezed into leftover evenings and weekends. Those Fridays are focused, intentional, and deeply creative. Knowing that my time is limited has sharpened my decision-making. I arrive in the studio knowing what I want to work on, and I let go of the pressure to produce constantly. Constraints, in that sense, have become a gift. They’ve taught me how to work with clarity instead of chaos. Motherhood has also transformed how I see the women I paint. It has deepened my understanding of quiet strength, patience, and resilience. My engineering career brings structure, discipline, and systems thinking into my creative life, while art keeps me connected to emotion and intuition. Together, these roles don’t compete with each other, they support each other. My creative practice exists not despite my life, but because of how intentionally it’s been shaped around it.

Q5. How do you define success for your art practice? Is it in connection with viewers/collectors, in the expression of your own voice, in teaching others, in commercial viability or a blend of these?

I see success as a blend, and that distinction matters to me. At the core, success begins with honesty, whether I’m expressing my own voice in a way that feels true, even when it evolves or feels uncomfortable. If the work doesn’t feel aligned to who I am and what I’m exploring, nothing else really holds. Connection comes next. When a viewer or collector sees themselves reflected in my work emotionally, that’s deeply meaningful to me. Those moments of recognition, when someone feels understood or quietly moved, tell me that the work has done what it needed to do. Teaching also sits close to my heart, as an extension of the same impulse, to share, to guide, and to help others find confidence in their own creative voice. Commercial viability matters too, and I don’t shy away from that. Being able to sustain a creative practice financially is a form of respect, both for the work and for the time, energy, and thought that goes into it.

But I don’t measure success purely in numbers or sales. For me, it’s about building a practice that is honest, connected, generous, and sustainable over time. When those elements are in balance, that’s when I feel successful

Q6. What keeps you motivated on days when inspiration feels elusive or when you encounter “artist-blocks”? How do you sustain the creative spark?

I’ve actually never experienced what I would call an artist block, and I think that surprises people. The reason is very practical. I never work on just one painting at a time. I usually have twenty five to thirty works in progress in my studio, all sitting at different stages of completion. So when I step into the space, there is always paintings that are waiting for me, even if it’s just a small decision or a few quiet marks on it. Some paintings do ask for more time. There are artworks that I leave untouched for weeks because the feeling isn’t quite right yet or I’m not in the mood to continue with it, and I’ve learned to respect that rather than push through it. But that doesn’t mean my creative practice stops there. It simply shifts to another one that is waiting for me. While one artwork rests, another moves forward. That rhythm keeps the energy flowing without forcing inspiration to show up on demand. For me, the creative spark is sustained through momentum and trust. I trust that ideas don’t disappear just because I step away from one canvas. Working in layers, both emotionally and physically, mirrors how creativity actually works for me. It’s not a single straight line, it’s a living system. As long as I keep showing up to the studio and engaging with what’s already there, inspiration takes care of itself.

Q7. You’ve built a global audience (teaching more than 25,000 students) and you manage many roles: maker, teacher, marketer, fulfiller. What have been the biggest challenges of wearing all those hats?

If I’m being truthful, I don’t experience wearing multiple hats as a burden. That’s because I never tried to juggle everything at once in a chaotic way. Very early on, I leaned into systems, structure, and clear boundaries. Teaching, making, marketing, and fulfilling aren’t competing roles in my mind, they’re interconnected parts of the same ecosystem for me. Each one feeds the other. Teaching sharpens my thinking, marketing helps me articulate my voice, and making art keeps everything grounded and meaningful. The only real challenge, if I had to name one, is being intentional about energy rather than time. Knowing when to switch hats and when not to. I don’t create art while thinking like a marketer, and I don’t teach while second guessing my creative instincts. That separation has been crucial. Once I’m in a role, I’m fully there. That clarity removes a lot of the friction people associate with doing many things. I also think my engineering background plays a quiet but important role here. Systems thinking comes naturally to me, so instead of reacting to overwhelm, I design workflows that support the life I want to live. Because of that, managing multiple roles doesn’t feel like pressure. It feels like alignment. When everything has its place, the hats don’t feel heavy at all.

Q8. Your choice of mixed-media, portraits, abstracts: how do you decide the boundary between figuration and abstraction in your pieces? Are there recurring motifs, forms or colour palettes you return to?

This part of my process is actually very intentional, even if the final result feels intuitive. Every painting begins digitally on my iPad. I design the portrait, the background, and the overall mood first in procreate or Pixelmator Pro in my laptop, so I already know who this woman is, what she carries, and what the painting is trying to say emotionally. That initial design gives me clarity and direction before I ever touch the canvas. Once I move to the physical artwork, I always begin with the background. This is where things loosen up. Even though I have a reference, I let go of control at this stage and allow abstraction, texture, and instinct to take over. I layer paint, add marks, respond to what’s happening on the surface, and let the energy of the moment guide me. That phase is very much about creative flow, about listening rather than deciding. The background almost sets the emotional temperature of the piece. Only after that do I start with the portrait. The figure usually is close to the reference that I designed, but it subtly adapts to the background that I have made. The colours might shift, or edges soften, lines respond to the movement that is already present in the background. The portrait isn’t imposed on the abstraction, it’s placed into a space that already has its own life and history. There are elements I return to again and again without forcing them. Spray paint marks, jagged lines made with solid markers, and flying petals appear naturally in my work. I don’t overthink them. The flying petals, especially, is something that I keep returning to in every painting. For me, the boundary between figuration and abstraction isn’t about deciding how much to reveal or hide. It’s about allowing structure and intuition to coexist. The planning gives the work meaning and grounding, and the abstraction gives it soul. The conversation between those two is where the painting truly comes alive.

Q9. Are there any pieces that felt like turning points for you moments where you discovered something new about yourself or your practice? We’d love to hear about one that holds special meaning.

Yes, absolutely. Dancing with Sunshine was a very clear turning point for me, both technically and creatively. It was the first time I consciously applied my understanding of facial planes instead of trying to soften and blend everything in a more traditional way. I allowed the structure of the face to show, and leaned into a pop art, slightly cubist language that felt bold and vibrant. What’s interesting is that even before I shared it anywhere, I knew something had clicked. As I was painting it, there was this strong internal clarity, this certainty that this was how I wanted my portraits to exist going forward. It felt truer to me than soft, polished realism ever had. The angles, the planes, the graphic quality of the face paired with expressive colour and abstraction, it all suddenly clicked into place. The fact that it went viral and sold immediately was validating, of course, but that wasn’t what made it special. The real moment happened earlier, alone in the studio, when I realised I had found a visual language that felt like home. Dancing with Sunshine showed me that I didn’t need to fit into existing portrait traditions to be taken seriously. I could honour structure, strength, and expression in my own way, and that discovery has shaped every portrait I’ve created since.

Q10. What advice would you give to emerging artists who are juggling multiple roles (like you have) and wanting to carve out their voice?

I would say, first and foremost, keep practising and keep dreaming, even on days when neither feels particularly productive. Your voice doesn’t appear fully formed, it reveals itself through repetition, curiosity, and trust. One of the most practical things that has helped me is always having multiple works in progress. When you have several pieces at different stages, you never really get stuck. There is always something you can return to, something waiting for you, and that alone removes so much pressure around inspiration. Create a dedicated space for your art, even if it’s small, even if it’s just a corner. What matters is that it’s ready for you. When the setup takes minimal effort, you’re far more likely to show up consistently. Alongside that, protect a specific time for painting, a time of day or a day of the week, and treat it as non-negotiable. You don’t need to wait to feel inspired. Your unfinished works will guide you back in. And perhaps most importantly, never believe that you have to choose between who you are. I never chose between engineering and art because I genuinely love both. Passion is what sustains this kind of life, not strategy or escape plans. I see many artists creating with the sole goal of quitting their full-time job, and while that can work for some, it can also lead to burnout if the rhythm and passion aren’t there yet.

For me, art isn’t about what I get out of it financially or where it might lead. It’s about love for the process, for science, for creativity, for making. When passion drives you, everything else finds its place naturally.

As we wrapped our conversation with Geethu, one thing became undeniable: the narrative that serious artists must choose between stability and creativity is a lie we keep telling ourselves.

What struck me most about her practice isn’t that she “balances” multiple roles it’s that she refuses to see them as opposing forces. Engineering taught her structure and systems thinking. Art gives her emotional freedom. Motherhood deepened how she sees strength in the women she paints. Each part feeds the others instead of competing for space.

What Geethu represents isn’t a blueprint everyone should follow not everyone loves their day job, not everyone has access to four-day work weeks, not everyone’s creative rhythm matches hers. What she represents is permission to design your life around what you actually love instead of what the mythology says you should sacrifice.

The art world’s obsession with suffering-as-proof-of-seriousness has always been suspect. Geethu’s practice offers a different model: clarity about what sustains you, intentional design of how you spend time, systems that support rather than fight your reality, and refusal to choose between parts of yourself that all contribute to who you are.

She reminded me that voice doesn’t appear fully formed. It reveals itself through repetition, curiosity, trust. That multiple works in progress remove pressure around inspiration. That dedicated space matters even if it’s small. That protected time matters even if it’s one day a week. That you don’t need to wait to feel inspired unfinished work guides you back in.

Most importantly, she proved that passion for two things can coexist without diminishing either. When you genuinely love both, when both feed something essential in you, the question isn’t “which one do I choose” but “how do I design my life so both thrive.” That’s not balance. That’s integration.

Follow Geethu from the links below to see what sustainable creative practice actually looks like when it’s built on passion instead of escape, on design instead of hope, and on the radical idea that you don’t have to choose between who you are.