Why do her images feel like memory learning to breathe again

👁 85 Views

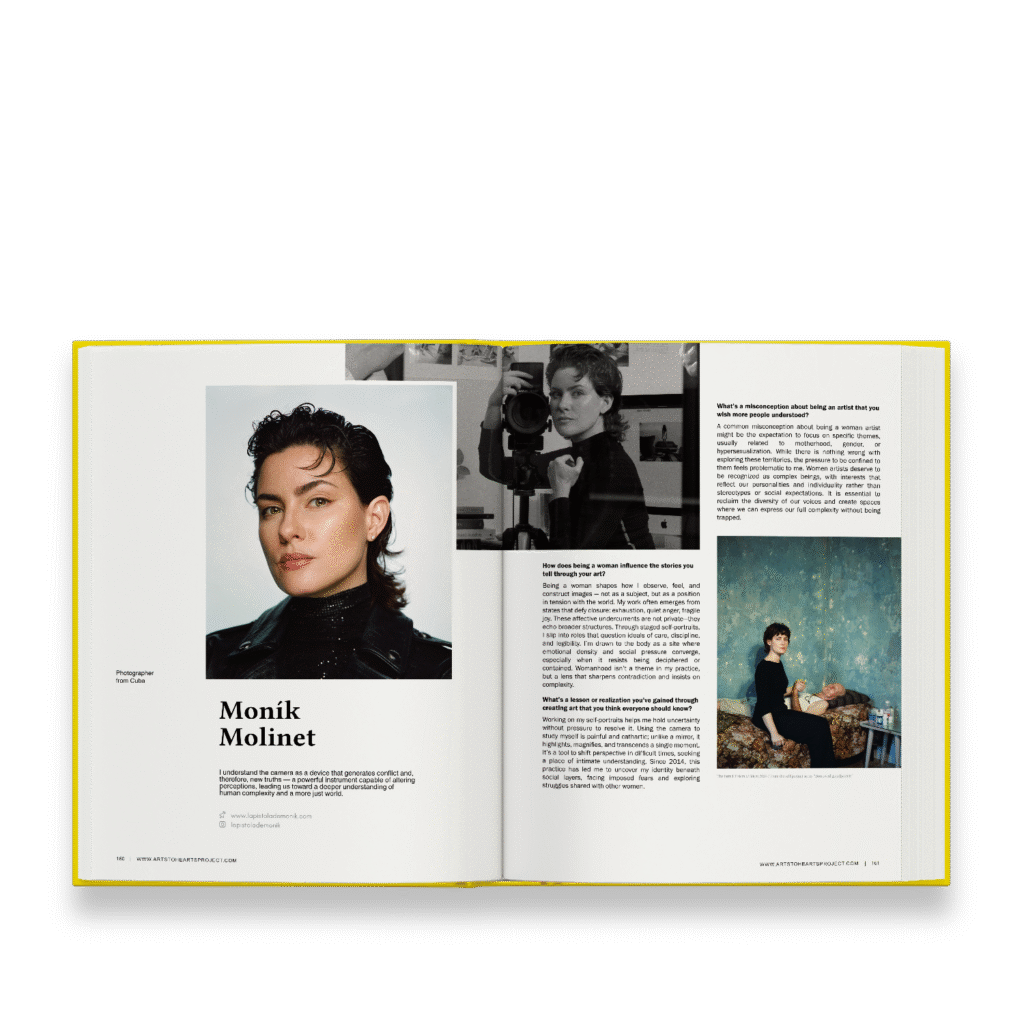

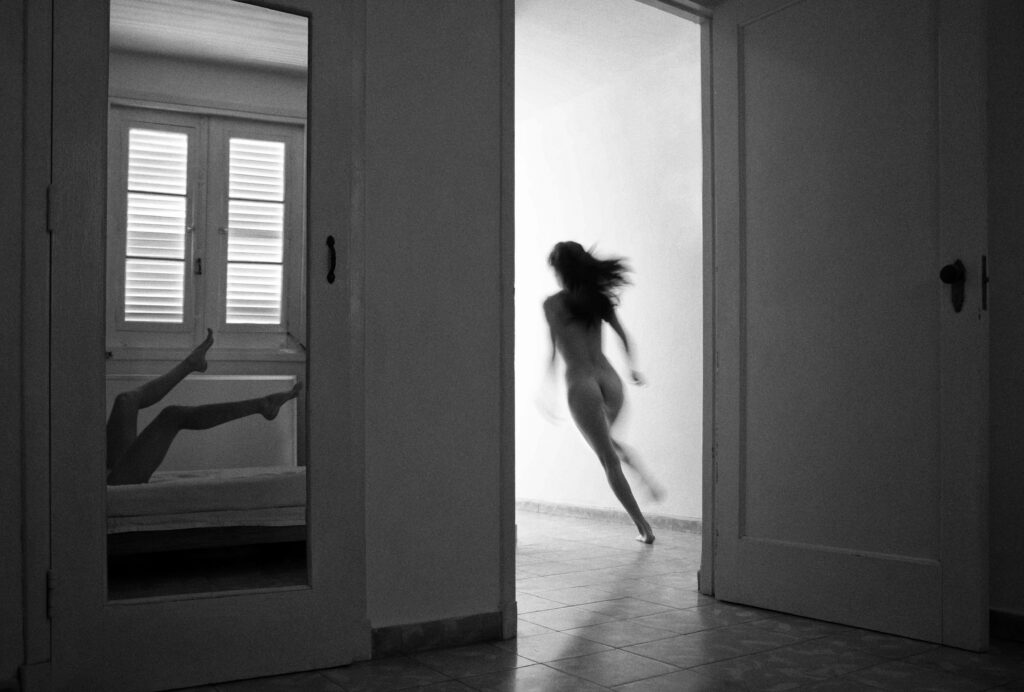

This interview follows Cuban photographer Moník Molinet through the ideas and experiences that have shaped her path so far. She talks openly about the questions that keep her returning to portraiture and the camera’s strange ability to stir tension, reveal things we didn’t expect, and shift conversations in surprising directions. Her series Masculinities, which traveled far beyond her initial circle, becomes a point of departure for discussing stereotypes, public debate, and how reactions from viewers can reshape an artist’s understanding of a project long after it is finished.

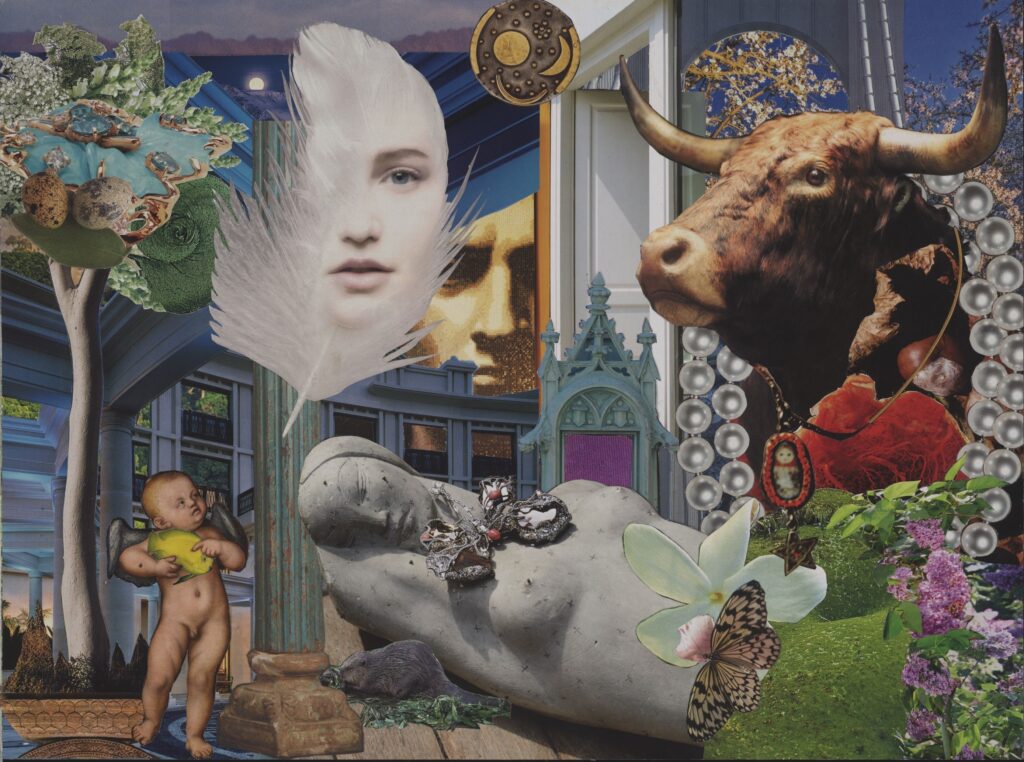

Molinet also revisits her long relationship with self-portraiture. She explains how it has changed for her over the years, moving from a way of looking at herself to a method that helps her explore shared situations and memories. Her series Borrowed Grandmothers and Grandfathers illustrates this shift, showing how a personal absence can turn into a space where others recognize parts of their own histories.

Her early training in music and theater appears throughout the interview as she describes how rhythm, staging, and performance still guide the way she builds an image or moves through a session. She talks about working in Cuba and Mexico, noting the different conversations that emerge in each place, and how international programs such as UNESCO Transcultura and PhotoEspaña encouraged her to question what a photograph can become beyond a print.

She closes with clear advice for young photographers who want to address identity and representation, stressing the importance of knowing why a subject matters to them and staying aware of their position when approaching it. Through her answers, we gain a sense of a practice shaped by curiosity, persistence, and a steady commitment to questioning whatever feels settled.

Moník Molinet is a featured artist in our book, “Art and Woman 2025” You can explore her journey and the stories of other artists by purchasing the book here:

https://shop.artstoheartsproject.com/products/art-and-woman-edition-

Moník Molinet, Pinar del Río, 1989. Cuban visual artist engaged in a sustained search for human identity through portraiture and self-portraiture — a practice she has pursued for over a decade. Her work addresses feminist themes such as masculinities, stereotypes, and romantic love, as well as conceptual inquiries related to meta-photography, accumulation, time, and the camera as a device capable of generating conflict and, therefore, new truths. She graduated from the National School of Arts in Havana and, after several years as an actress, was driven by ontological concerns to begin working in the visual arts as a self-taught artist upon her arrival in Mexico in 2014. Since then, photography has become her primary medium. She has received international recognition through several awards, including Humans of the World granted by the Life Framer platform. Her series Borrowed Grandmothers and Grandfathers was selected by the jury of the OD Photo Prize 2024 (OpenDoors Gallery) and received an Honorable Mention in Innovate Grant 2024.

1. Your series “Masculinities” reached people all over the world. What first made you want to explore this topic, and how did people’s reactions affect the way you see the project now?

What led me to create Masculinities was likely two fundamental factors: my firm conviction about the urgent need to question all stereotypes —in this case, those that reinforce a limited and patriarchal view of masculinity— and my ongoing pursuit of understanding the camera as a device that generates conflict and, consequently, new truths, as a powerful instrument to foster reflection and change. This was one of the first projects in which the camera became a tool to highlight conflict. Undoubtedly, the audience’s reactions and the intensity of the debate generated internationally convinced me of photography’s ability to raise awareness and open spaces for dialogue: such exchanges are essential for addressing issues and envisioning potential solutions.

What led me to create Masculinities was likely two fundamental factors: my firm conviction about the urgent need to question all stereotypes, in this case, those that reinforce a limited and patriarchal view of masculinity, and my ongoing pursuit of understanding the camera as a device that generates conflict and, consequently, new truths, as a powerful instrument to foster reflection and change. This was one of the first projects in which the camera became a tool to highlight conflict. Undoubtedly, the audience’s reactions and the intensity of the debate generated internationally convinced me of photography’s ability to raise awareness and open spaces for dialogue: such exchanges are essential for addressing issues and envisioning potential solutions.

A self-portrait can reveal truths that terrify us and help process experiences that stay beneath the surface.

Moník Molinet

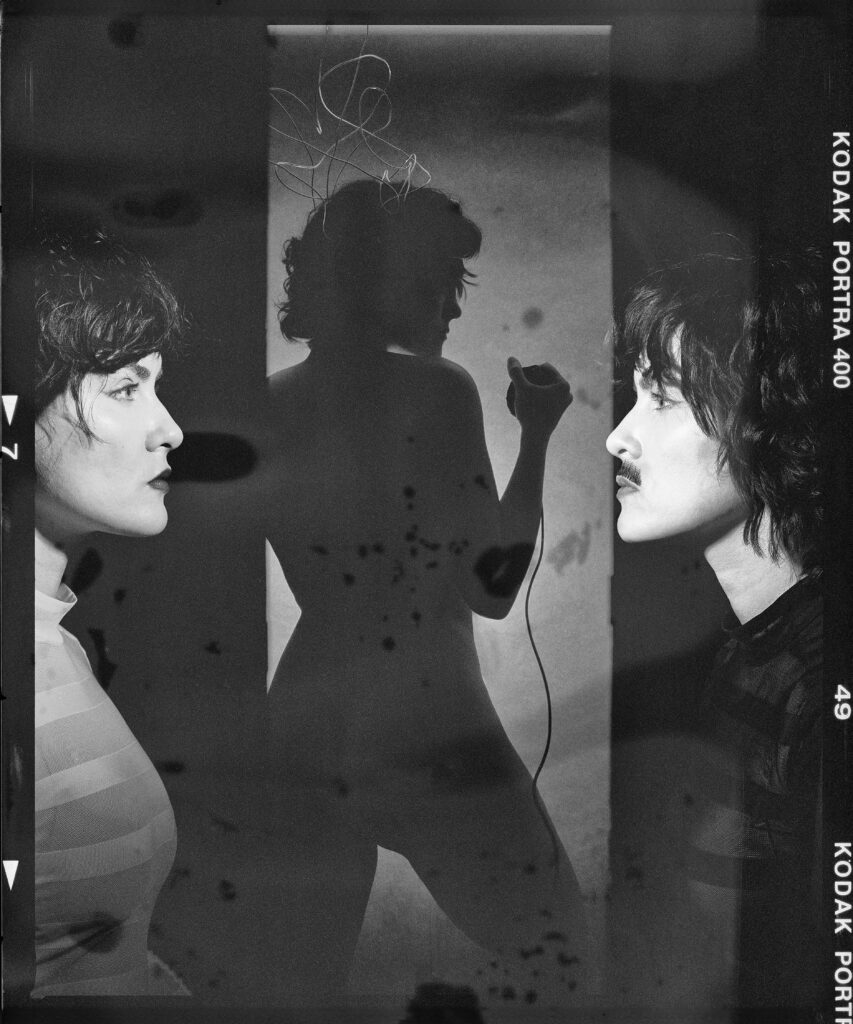

2. You’ve been working with self-portraits for more than ten years. What keeps you interested in turning the camera toward yourself after so long?

It’s a very interesting question. Over the course of this practice, sustained for more than ten years, my relationship with self-portraiture has matured profoundly. For me, a self-portrait goes far beyond simply depicting oneself; it can reveal truths that terrify us and become the most intimate instrument for understanding and processing deeply psychological experiences. Any subject can be approached from the subjective perspective that a self-portrait establishes. It can be an exercise in which the boundaries that define who we are at a given moment are either challenged or reaffirmed: something humanly true, complex, and ever-changing. However, I have also learned that a self-portrait does not always speak solely about the person being depicted. Although I am present in all of my portraits and do not hide behind the desire to be someone else, I can serve as a vehicle to speak, from my own position, about other women and situations we share as human beings. For example, Borrowed Grandmothers and Grandfathers is a series of self-portraits that emerged from identifying a profound personal absence: my relationship with my grandparents, and attempting to fill it through art. From there, I pushed the limits of staging and performance to create a photographic memory that did not exist. Yet the series does not only speak about me; it ended up generating an emotional map in which viewers recognized powerful codes from their own histories and relationships with their grandparents. In that sense, the series transcended me: people discovered their own stories; these were photographs that spoke to them, about the grandparents they had or the ones they wished they had. Ultimately, the way I understand self-portraiture goes far beyond the simple act of photographing myself; it can stem from multiple starting points and, for me, it is a fascinating and profoundly potent photographic genre that never ceases to offer new possibilities.

It’s a very interesting question. Over the course of this practice, sustained for more than ten years, my relationship with self-portraiture has matured profoundly. For me, a self-portrait goes far beyond simply depicting oneself; it can reveal truths that terrify us and become the most intimate instrument for understanding and processing deeply psychological experiences. Any subject can be approached from the subjective perspective that a self-portrait establishes. It can be an exercise in which the boundaries that define who we are at a given moment are either challenged or reaffirmed: something humanly true, complex, and ever-changing. However, I have also learned that a self-portrait does not always speak solely about the person being depicted. Although I am present in all of my portraits and do not hide behind the desire to be someone else, I can serve as a vehicle to speak, from my own position, about other women and situations we share as human beings. For example, Borrowed Grandparents is a series of self-portraits that emerged from identifying a profound personal absence: my relationship with my grandparents, and attempting to fill it through art. From there, I pushed the limits of staging and performance to create a photographic memory that did not existen before. Yet the series does not only speak about me; it ended up generating an emotional map in which viewers recognized powerful codes from their own histories and relationships with their grandparents. In that sense, the series transcended me: people discovered their own stories; these were photographs that spoke to them, about the grandparents they had or the ones they wished they had. Ultimately, the way I understand self-portraiture goes far beyond the simple act of photographing myself; it can stem from multiple starting points and, for me, it is a fascinating and profoundly potent photographic genre that never ceases to offer new possibilities.

3. You started out studying music and performing arts before moving into photography. How do those early experiences still show up in the way you create your images today?

I believe that my training in classical music and performing arts has, without a doubt, shaped a very distinctive identity as a visual artist. All of those learnings manifest in one way or another in the way I approach a project, in the tools I put at my disposal, such as acting, or in elements like rhythm, harmony, and dynamics that I learned through my musical studies. I feel that a photography session, the editing of images, and even curation are closely related to a musical score: there must be dynamics, fortes, mezzo-fortes, pianos, pauses, and endings. On the other hand, I believe that venturing into different areas of knowledge, always within the realm of art, has helped me reinforce my identity as a curious and restless self-taught artist.

In Cuba, I feel that the tradition of widespread engagement with art makes people much more open to experiencing it and engaging in conversations around it. Perhaps that is why I prefer to develop much of my work there. For me, it is very important to communicate as an artist with the audience; especially in works that address activism-related themes, since without that solid bridge, the work would completely lose its meaning and impact. On the other hand, it has been incredibly rewarding to discover that pieces developed in a specific context can later transcend it and be understood in any other country. This relates to identifying themes that are not confined to a local context.

A photography session, the editing of images, and even curation feel connected to the rhythm and pauses I learned through music

Moník Molinet

5. Being part of the UNESCO Transcultura program and PhotoEspaña must have opened new doors. How has that experience changed the way you think about your work or your audience?

It was a fantastic opportunity and experience: talks, workshops, exhibitions, debates, networking. Without a doubt, it enriched me greatly, but above all, it guided me toward the pursuit of experimenting with photography beyond a result on paper, to explore, from a contemporary perspective, how an image is constituted, and it encouraged me to continue developing my own visual language along that path.

6. In your talks and workshops, you connect gender and image-making. What advice would you give to young photographers who want to tell stories about identity or representation?

First, I would tell them to discover what truly affects them as people and as artists —what moves them, what unsettles or bothers them— as this can be an excellent strategy to define what they want to say. If they don’t feel a deep connection with the subject, it is probably not worth addressing. Second, it is essential to be very aware of one’s own position when addressing identity and gender, to avoid appropriating or speaking over the voices of others.

First, I would tell them to discover what truly affects them as people and as artists, what moves them, what unsettles or bothers them, as this can be an excellent strategy to define what they want to say. If they don’t feel a deep connection with the subject, it is probably not worth addressing. Second, it is essential to be very aware of one’s own position when addressing identity and gender, to avoid appropriating or speaking over the voices of others.

Speaking with Moník Molinet gives a clear sense of what sits at the center of her work. She uses portraiture and self-portraiture to look at identity, gender, memory, and the uneasy space between what we think we know and what the camera exposes. Her path shows how an artist grows by questioning limits, by stepping into conversations that are sometimes uncomfortable, and by allowing each project to teach her something new.

Through Masculinities, she confronted long-standing stereotypes and saw how an image can prompt wide public discussion. Through Borrowed Grandmothers and Grandfathers, she explored absence and discovered how staged memories can open a space for viewers to recognize parts of their own stories. Her journey shows how thoughtful inquiry, careful staging, and a willingness to challenge expectations can turn photography into a tool for asking better questions about who we are and how we see each other.

To learn more about Moník Molinet, click the following links to visit her profile.

Arts to Hearts Project is a global media, publishing, and education company for

Artists & Creatives. where an international audience will see your work of art patrons, collectors, gallerists, and fellow artists. Access exclusive publishing opportunities and over 1,000 resources to grow your career and connect with like-minded creatives worldwide. Click here to learn about our open calls.