Why is being curious better than being certain| Shannon Soldner

👁 45 Views

This interview offers a chance to get to know Shannon Soldner not only as a painter but as someone who spends long, quiet hours considering how we remember, how we see, and how those things shift over time. She discusses her approach to navigating the balance between clarity and looseness in her work, leaving space for uncertainty rather than trying to tie everything up neatly. What she shares feels like an invitation to slow down and notice the things that usually slip past.

Throughout our conversation, Shannon opens up about her studio rhythm, the way she senses when a painting has reached its point of rest, and how humour sneaks into the work to keep things light when ideas start to feel heavy. She approaches painting with curiosity rather than pressure, allowing moments to unfold rather than forcing them. Hearing her describe that process makes the act of looking feel just as important as the act of making.

Her life in Rocheport and involvement in the Columbia art community come through as steadying forces. She talks about the calm pace, the space to think, and the value of a community that is invested, supportive, and close enough for real conversation. Missouri isn’t simply a backdrop for her studio; it’s part of the quiet that feeds her practice and allows her to paint on her terms.

Shannon also shares stories of how people respond to her work, including moments when viewers physically mirror the figures in her paintings without even realising it. Those reactions stay with her, not because they prove she succeeded at something, but because they show how a painting can stir something familiar in someone else. By the end of this interview, you leave with a sense of someone who thinks carefully, works with patience, and creates space for wandering thoughts. You also come away with something subtle but lasting: a new way to pay attention to how you see the world, and how memory shapes the stories you carry.

Shannon Soldner is a featured artist in our book called “The Great Book of Art Makers” You can explore her journey and the stories of other artists by purchasing the book here:

https://shop.artstoheartsproject.com/products/art-and-woman-edition-

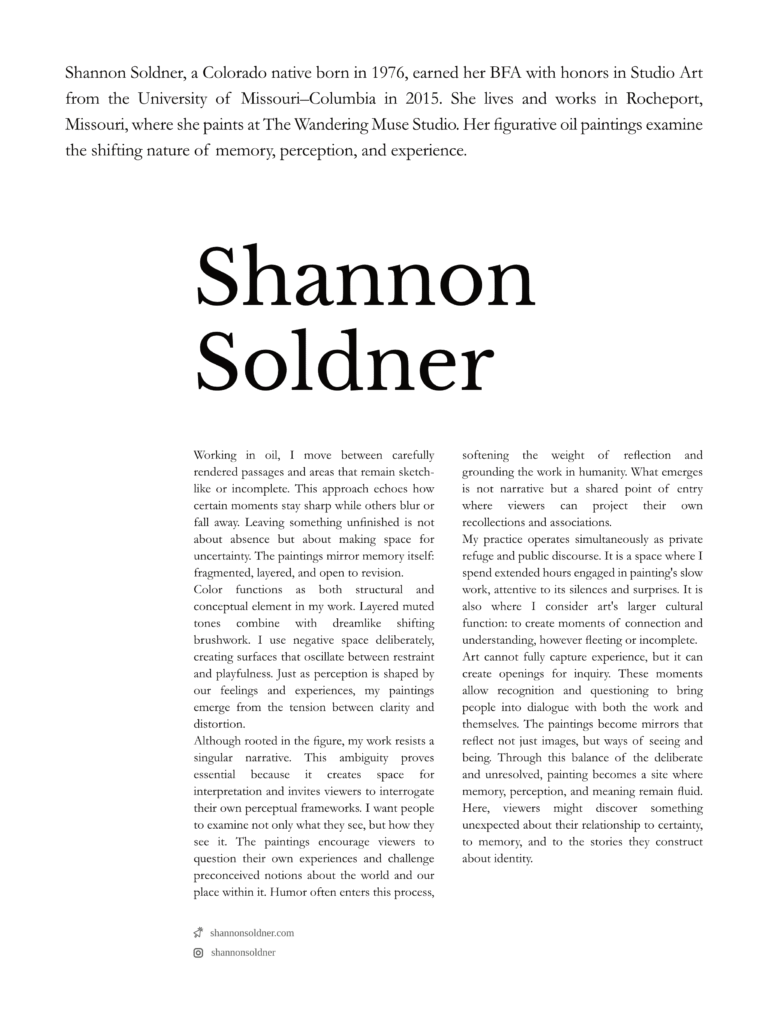

Shannon Soldner, a Colorado native born in 1976, earned her BFA with honours in Studio Art from the University of Missouri–Columbia in 2015. She lives and works in Rocheport, Missouri, where she paints at The Wandering Muse Studio. Her oil paintings investigate memory, perception, and the ever-changing nature of shared experience.

1. Your paintings move between precision and openness, holding both memory and uncertainty. How do you sense when a piece is ready to stop evolving?

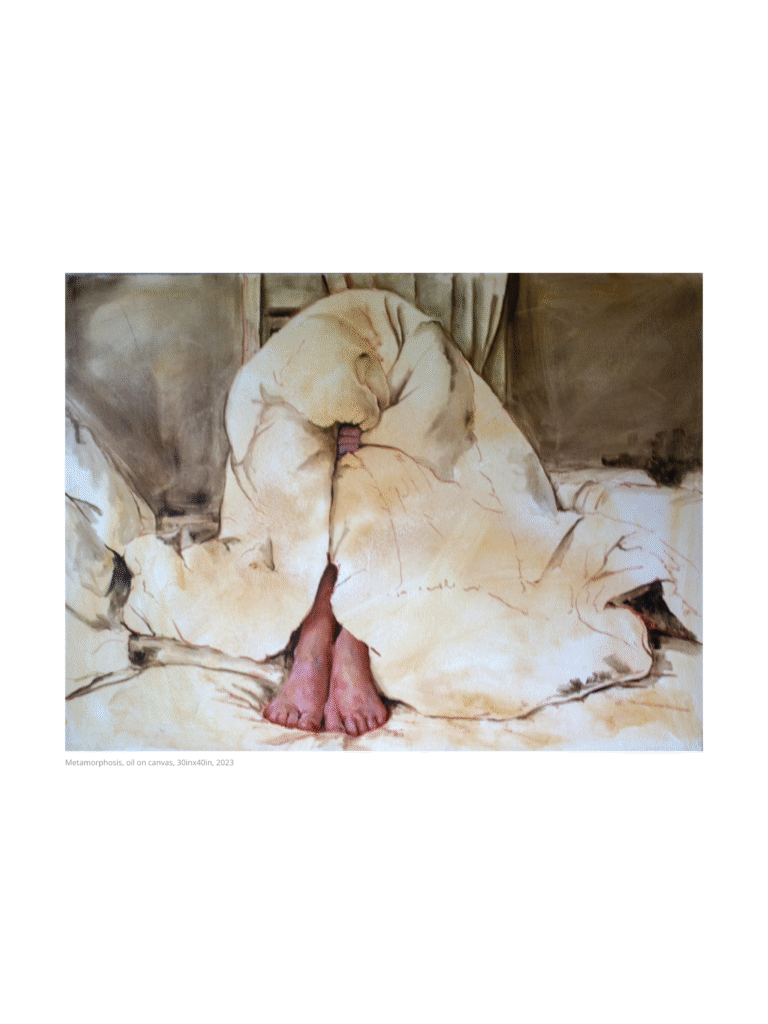

When a painting is finished, it sometimes feels like a moving target. Holding the tension between what is rendered fully and what is allowed to be loose and gestural is felt more than planned. Not every piece becomes what I envision, but each one pulls me closer to an overall balance for the entire body of work.

Humor acts as a release valve keeping my work from becoming too precious or self-serious. I believe that humor makes the paintings more approachable, more human.

Shannon Soldner

2. There’s a quiet humour that runs through your work. How does that play a role in how you paint or how you hope people experience your pieces?

Humour acts as a release valve, keeping my work from becoming too precious or self-serious. In the studio, it might show up in an unexpected gesture, a playful bit of colour, or in leaving something deliberately unresolved when the impulse is to overwork it. I believe that humour makes the paintings more approachable, more human. It creates permission for viewers to enter the work without feeling like they need to decode something heavy or theoretical. There’s already enough weight in exploring memory and perception; humour softens that and reminds us that ambiguity can be lighthearted, even joyful.

3. You live and work in Rocheport and are active in the Columbia art community. How has being rooted in Missouri influenced your approach to painting?

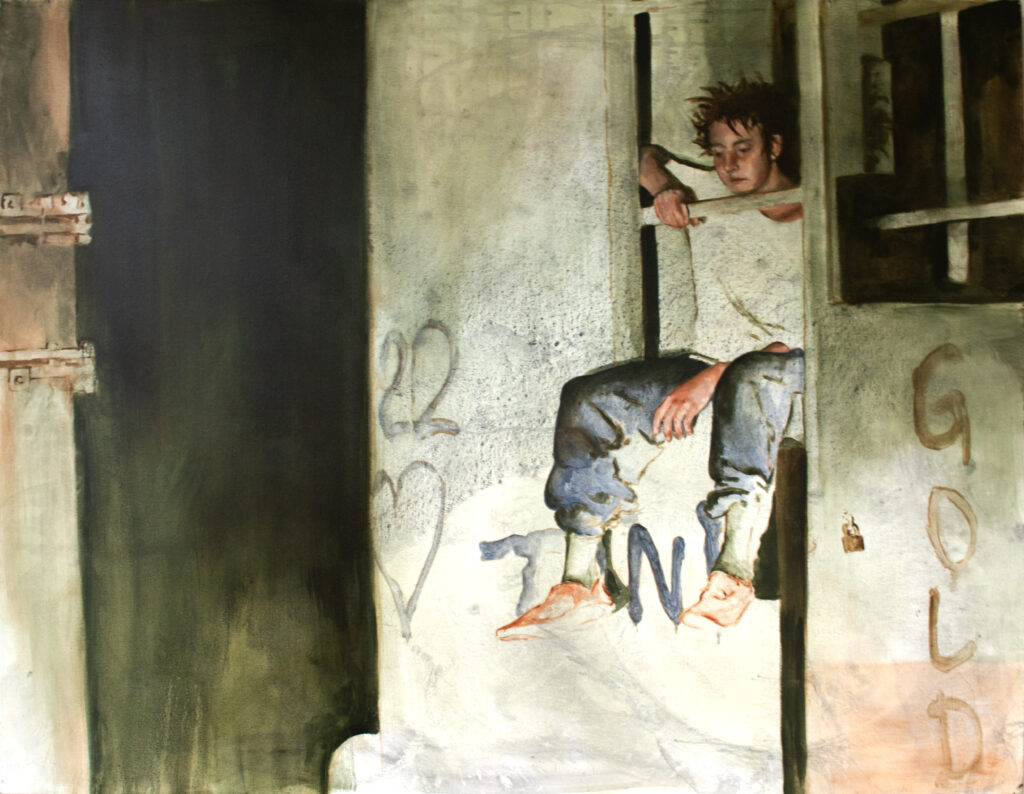

The Midwest and Rocheport, in particular, give me a quieter space—both literally and psychologically. There’s less noise competing for attention, which allows for the sustained looking and thinking that painting demands. The Columbia art community is intimate enough to foster genuine relationships, yet robust enough to maintain meaningful dialogue. I’m not isolated, but I’m also not overwhelmed. That balance feels essential to my practice. Being rooted here also means I’m less caught up in art world trends or the pressure to produce work that fits a particular moment. There’s freedom in that distance. The pace here matches the pace of painting: slow, deliberate, and attentive to slight shifts. And honestly, the landscape itself, with its layers of history and quiet beauty, probably seeps into how I think about layering and atmosphere in the work.

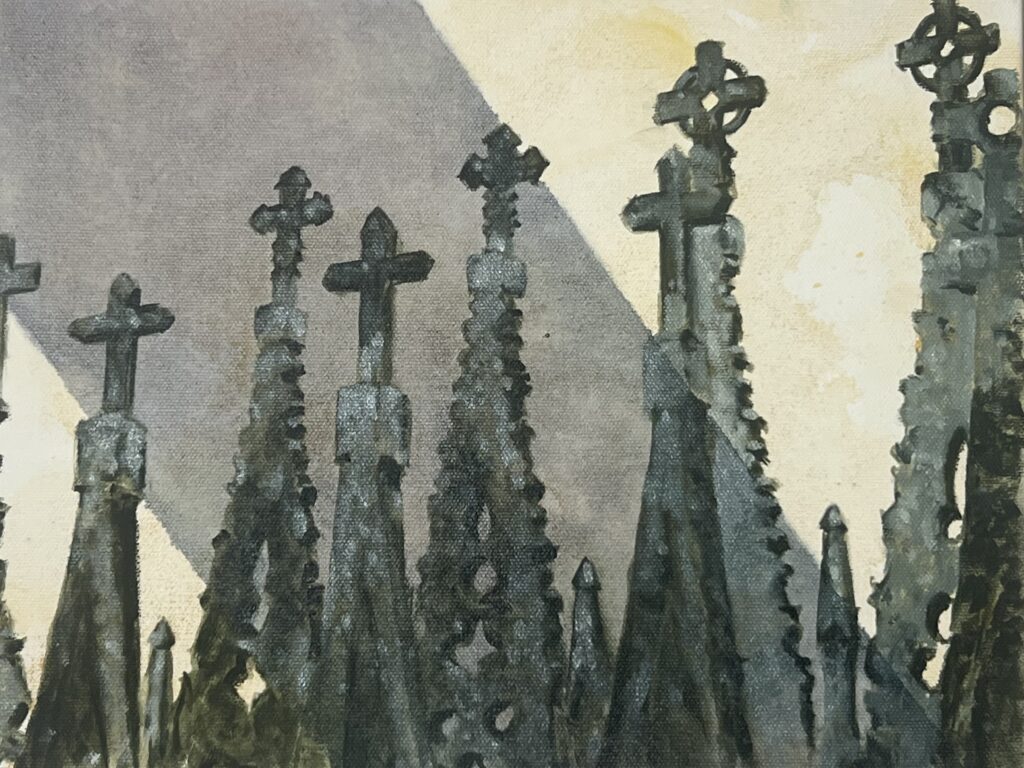

4. Your palette often leans toward soft, layered colour. What keeps you drawn to those tones, and what do they let you explore about memory or time?

I tend to use a limited palette, which functionally keeps the work cohesive and prevents it from becoming chaotic. But beyond that practical consideration, those soft, layered colours create a dreamlike quality that speaks directly to how memory operates. Memories don’t come to us in bright, crisp focus. They arrive hazily, atmospherically, with colours that have been softened by time and emotion. The layering itself becomes a metaphor: experiences don’t sit separately in our minds; they bleed into one another, influence each other, and create new meanings through their accumulation.

A muted raw umber might sit under a bright alizarin crimson, which gets glazed over with a cooler tone, and suddenly there’s this depth and complexity that mirrors how our past experiences inform present perception. It’s not about nostalgia or sentimentality at all. It’s about acknowledging that memory is never singular or fixed. It’s constantly shifting, always layered, always filtering through everything we’ve seen and felt before.

When a painting is finished, it sometimes feels like a moving target. Holding the tension between what is rendered fully and what is allowed to be loose and gestural is felt more than planned.

Shannon Soldner

5. Your work invites people to think about how they see things, not just what they see. Has any reaction or conversation from viewers ever stayed with you?

This question makes me think especially of one particular painting, Metamorphosis, where I’ve repeatedly watched viewers actually mimic the pose. They’ll wrap their arms around themselves or tilt their heads, imagining themselves cocooned in that comforter, wanting to hide away from the world. That physical, embodied response tells me something important: they’re not just looking at the figure; they’re feeling it in their own bodies, recollecting moments of their own need for refuge or transformation onto the image. Beyond that specific piece, what stays with me is how often viewers describe contradictory experiences with the same painting.

One person may see melancholy while another sees hope, and yet another sees humour. That multiplicity doesn’t bother me; it confirms to me that the ambiguity is working. I don’t intend for my paintings to prescribe a specific meaning; they create conditions for people to bring their own associations and discover something about their own way of seeing. When someone tells me they saw something I didn’t consciously intend, that feels like the painting doing precisely what it should. The work becomes alive beyond my control, reflecting not just images but ways of being.

6. Between teaching, leading, and painting, your days must take on many rhythms. How do those roles feed into each other and keep your practice moving forward?

I look at the time I spend in those roles as more seasonal rather than day-to-day. Each role needs its own space in which it can breathe and develop without competing for attention. Teaching and leadership work might dominate certain weeks or months, while other periods belong almost entirely to the studio. Trying to do everything simultaneously leads to fragmentation, and nothing gets my full attention. But those roles do feed each other in unexpected ways. Teaching forces me to articulate ideas about process, perception, and meaning that might otherwise stay intuitive.

When I’m explaining colour theory or how to build a composition, I’m also clarifying my own thinking. Being active in the arts community keeps me connected to broader conversations about what art does and who it’s for. The very questions that directly inform why I paint. As for my studio time, the slow work of painting grounds everything else. It’s where theory becomes real and where my ideas get tested against the material reality of brush and canvas.

Talking with Shannon feels a bit like stepping into a quieter room where you can actually hear yourself think. Her paintings take shape in that same atmosphere, where memory drifts in and out, and clarity sits right beside uncertainty. What we take from her work and her path isn’t a grand declaration or tidy lesson, but something steadier: the idea that slowing down changes what we notice, that questions matter just as much as answers, and that paintings can leave space for people to bring their own sense of time and experience.

Her journey demonstrates how patience and curiosity can guide a practice, and how living slightly removed from the noise can help ideas flourish.

To learn more about Shannon, click the following links to visit her profile.

Arts to Hearts Project is a global media, publishing, and education company for

Artists & Creatives, where an international audience will see your work of art, patrons, collectors, gallerists, and fellow artists. Access exclusive publishing opportunities and over 1,000 resources to grow your career and connect with like-minded creatives worldwide. Click here to learn about our open calls.