This Artist Draws the Invisible through Light and Shadow

👁 31 Views

Danja Akulin creates artworks that are both powerful and meditative. His drawings and paintings often explore the play of light and shadow, using countless layers of lines and marks to build depth, rhythm, and atmosphere. Trained in classical drawing yet unafraid to experiment, he combines precision with freedom, moving between abstraction and figuration. Much of his work reflects on themes of time, memory, and presence and how moments can leave invisible traces that art makes visible.

Over the years, his practice has grown into large-scale works that invite viewers to slow down and look closely, discovering subtle shifts and details within the surface. By focusing on something as elemental as light, Danja transforms ordinary perceptions into something poetic and profound. In this interview, he shares insights into his creative process, his journey as an artist, and the ideas that continue to shape his work.

With exhibitions across Europe and collectors drawn to his tactile, glassless canvases, Akulin describes how he has carved out a space as one of today’s most compelling contemporary draughtsmen.

You know, I grew up immersed in this world. My father was an Honored Artist of the USSR, so from childhood, I was essentially compelled to engage with art. I’ll be honest — back then I pursued it without particular enthusiasm, attending art school, various studios. But then something shifted when things began to work out, and genuine excitement emerged. Paradoxically, I’ve never felt an urgent compulsion to draw — it rarely surfaces even now. Probably because I’m drawing perpetually, always — sometimes more intensively, sometimes less. It became integral to who I am.

The trajectory toward drawing as my primary medium was circuitous. I experimented extensively, seriously pursued sculpture, then painting, until I grasped something fundamental: with a pencil I can articulate significantly more than with brushes and paints. A line executed with pencil is infinitely more compelling to me — it’s capable of conveying far greater information and nuance.

You moved from St. Petersburg to Berlin to study art. How did this shift influence your creative path?

It was a watershed moment in my life. I went seeking genuine artistic education — I harbored no specific intention to emigrate. I gained admission to Berlin University of the Arts when the stars aligned. The odds were infinitesimal: 300 candidates vying for a single place. My principal mentor became Georg Baselitz — a towering figure in contemporary art. We cultivated an exceptional personal rapport; he provided unwavering support and guidance, even facilitating my inaugural exhibition. Baselitz observed about my work: “Danja Akulin creates conceptual drawings. Since they originate from St. Petersburg, they appear distinctly different from equally conceptual art by Californian artist Ed Ruscha. This exemplifies what accomplished drawings should embody.” Subsequently came postgraduate studies under Daniel Richter — another seminal figure in German contemporary practice. The fundamental distinction I perceived in their pedagogical approach was the absence of rigid systematic structure. Each studio becomes its own microcosm. Baselitz, for instance, endeavored to excavate and cultivate each student’s distinctive visual vernacular for audience engagement. In Berlin, immediate visual sophistication emerged — galleries, museums proliferating everywhere. When my first exhibition took place, I was genuinely astonished that a collector inquired about acquiring my work. My initial reaction was: “Purchase it? This is art — it’s not for sale!” In Europe, gallerists begin cultivating relationships with artists during their studies. In 1995 Petersburg, such infrastructure was entirely non-existent.

Most of your works are in monochrome? Does that reflect any specific theme or emotion?

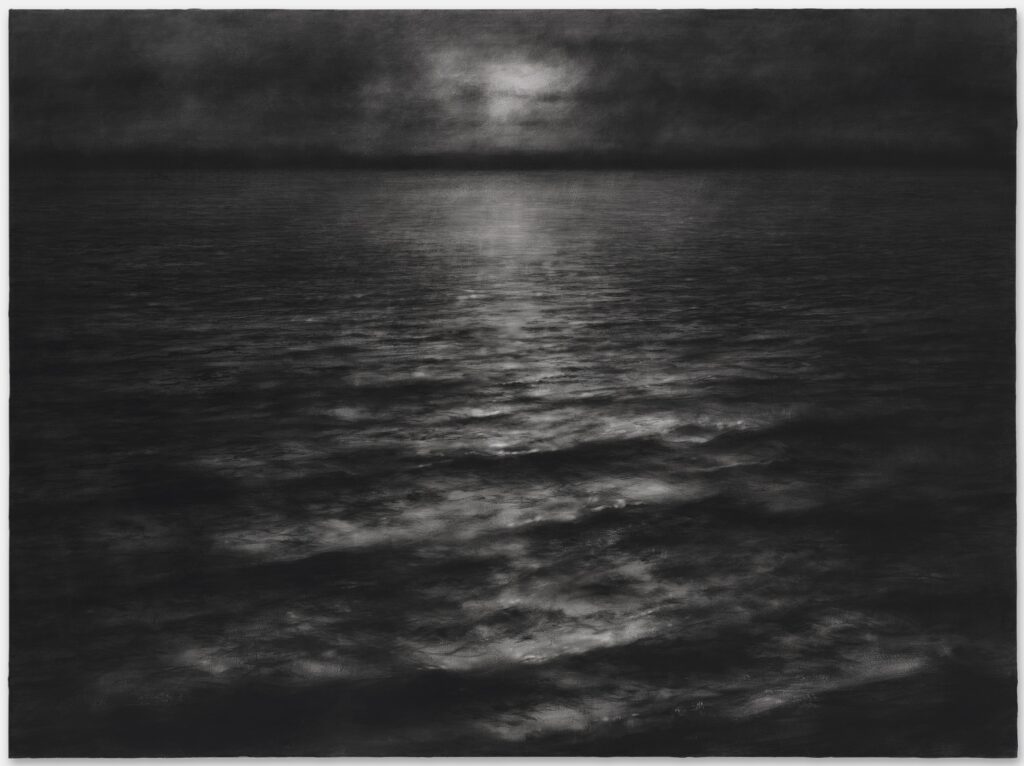

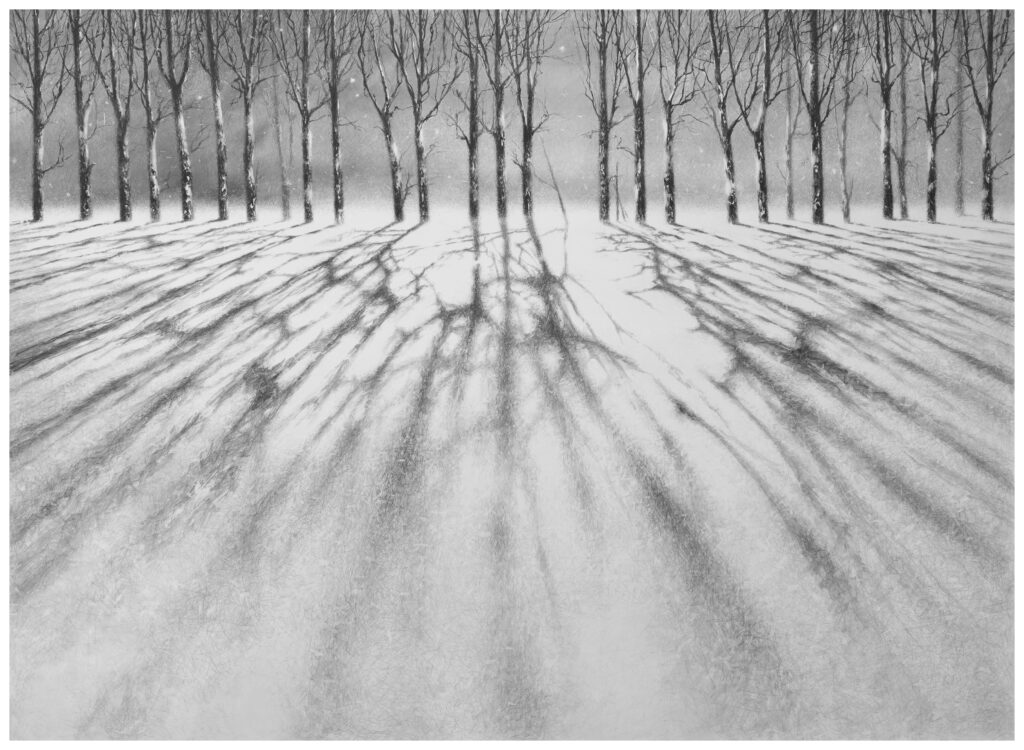

Monochrome actually brings me closer to reality rather than distancing me from it. Graphics represents something you either embrace wholeheartedly or reject entirely — there’s no middle ground. I’ve experimented with introducing color, tonal variations, but invariably recognize it as superfluous — it contributes nothing to the artistic statement, rendering it meaningless. My technique employs the most meticulous pencil hatching, subsequently transferred onto canvas. Black-and-white graphics is constructed exclusively through the interplay of light and shadow. In my “Penumbra” series — the term often rendered as “half-light,” derived from Latin paene umbra, literally signifying “almost shadow” — between shadow and light exists a zone through which we can see what’s in the penumbra, but we perceive it with this darkened hue. In these works, illumination radiates onto partially lit landscapes. Through this light, emotions and thoughts within the duality of darkness and brightness become visually translated. Truth resides precisely in this intermediate area — within the penumbra.

What are the main mediums you use and what do these materials mean to you?

For the majority of my practice I rely upon graphite, charcoal, and pencil. The singular development throughout my artistic evolution has been incorporating charcoal and graphite. Until 2010 I worked exclusively in pencil. The painterly qualities emerged not through chromatic application, but through brush techniques. This approach yielded genuine spatial depth. Communication through graphite and charcoal feels more intuitive — this constitutes my authentic visual vocabulary.

An artist’s fundamental obligation is developing their distinctive language and mastering articulate communication with viewers through it. In larger-scale works I modulate line thickness and refinement to achieve fusion and dissolution of contours. I employ the tactile qualities of my drawings as the primary vehicle for artistic expression.

I’ve developed a specialized technique: initially executing drawings on paper, subsequently transferring them onto canvas — the paper becomes mounted on the canvas support. This methodology enables my drawings to be exhibited without glazing, preserving the viewer’s direct engagement with textural qualities and light interplay.

If you were to select just one colour apart from black and white for your artworks, what would it be and why?

Perhaps in a decade I’ll be producing entirely different work. Presently I sense that working with pencil feels most authentic, and any chromatic additions would prove superfluous.

Does the process of creating something new get mundane at times? How do you overcome creative blocks?

For me, being an artist transcends mere profession — it embodies a way of life and thought. There are many examples of people who engage with art but never truly become artists because they perceive it purely as a profession. For an authentic artist, everything assumes significance — even what films they watch and with whom they associate. I perpetually seek inspiration — it constitutes a daily activity. Photography, natural phenomena, human conversations — all generate discoveries from which I extract ideas for subsequent works. What I find most gratifying about the creative process is that time stops. Or stretches. I literally conquer time while drawing. My methodology has evolved considerably throughout my career. Previously I didn’t stretch my works, so they resembled simple drawings requiring glazing. I found the glass barrier objectionable — it prevented direct experience of textural qualities and light play.

How do you control your strokes with changing emotions? How do you decide when to use faint or bolder ones?

I communicate visual imagery and psychological states. Format, materials, compositional structure, and tonal relationships — all these elements prove crucial in conveying intended meanings. Sometimes a 10×15cm work suffices, while other concepts demand the commanding presence of monumental formats. Currently I’m developing a series measuring 2×3 meters, generating tremendously powerful impact. When working at large scales, I modulate line weight and refinement. Clusters of pencil marks differ not merely in luminous intensity, thermal quality, and structural characteristics — they also possess varying visual mass. Through this weighted quality, dark spatial voids frequently become more materially substantial than the depicted subjects themselves. Elegant tranquility emerges through juxtaposition between intimate viewing distances and work dimensions: large canvases require spatial separation for proper appreciation. These appear as straightforward monochromatic images, yet they compel viewers to pause and engage deeply.

Your exhibition titles often centre around Light and Shadow. How do you generally title your works?

Titles crystallize from the essential nature of each body of work. Consider “Penumbra” — this represents a pivotal concept within my artistic investigation. Between shadow and illumination exists an ambiguous realm where truth inhabits this liminal territory. The “Signs” series synthesizes meticulous external draftsmanship with profound internal conceptualization. Electronic displays, diverse official emblems, elements of urban and domestic graphic systems — in their original manifestations they’re reduced and emotionally neutralized, yet here vitality becomes ritually infused into these depleted forms.

What keeps you inspired? Books, environments, or other artists?

My imagery operates simultaneously as abstraction, symbolism, and figuration. Trees, meadow grasses, placid lakes, the moon suspended gently above water surfaces — all these elements transform into sensuous and contemplative landscapes. I find inspiration in ubiquitous and sometimes intrusive symbols pervading daily urban experience — product packaging, computer interfaces. They become mysteriously absorbed within artistic contexts. I aspire to resolve the challenge of “Penumbra” — achieving harmony between half-light and half-darkness. I primarily render natural subjects, attempting to capture those moments when illumination engages with shadow most enigmatically. The conceptual education I received studying under masters like Baselitz and Richter, superimposed upon rigorously developed technical facility, enabled me to discover my distinctive artistic vocabulary.

What do you think might be the major challenge for emerging artists and what would be your advice to them?

For me, an artist represents an entire universe. However, for the contemporary art world, an artist increasingly resembles a startup with a team ranging from 5 to 500 people, like Damien Hirst. And I think this represents the main tendency in today’s art world. The primary problem is that many perceive art as merely a profession. But being an artist is a way of life and thought. My advice: don’t fear conflicts with established systems if you sense they impede your development. I left art school because I felt like a formed artist. This was audacious, yet ultimately correct. Be prepared that an artist’s path involves constant experimentation, constant search for your own language. And remember: art isn’t something you do — it’s something you live.

Through his practice, Danja Akulin reminds us that art is not a profession but a lived philosophy; a way of seeing and engaging with the world. His works, situated between darkness and illumination, invite us to pause, contemplate, and inhabit the liminal spaces where meaning quietly emerges. For Akulin, the act of drawing is not only about conquering time, but also about giving form to silence, shadow, and the ineffable truths that lie between.

To learn more about Danja, click on the link below.