Painstaking, Tiny Sculptural Recreations w/ Joanne Steinhardt

👁 82 Views

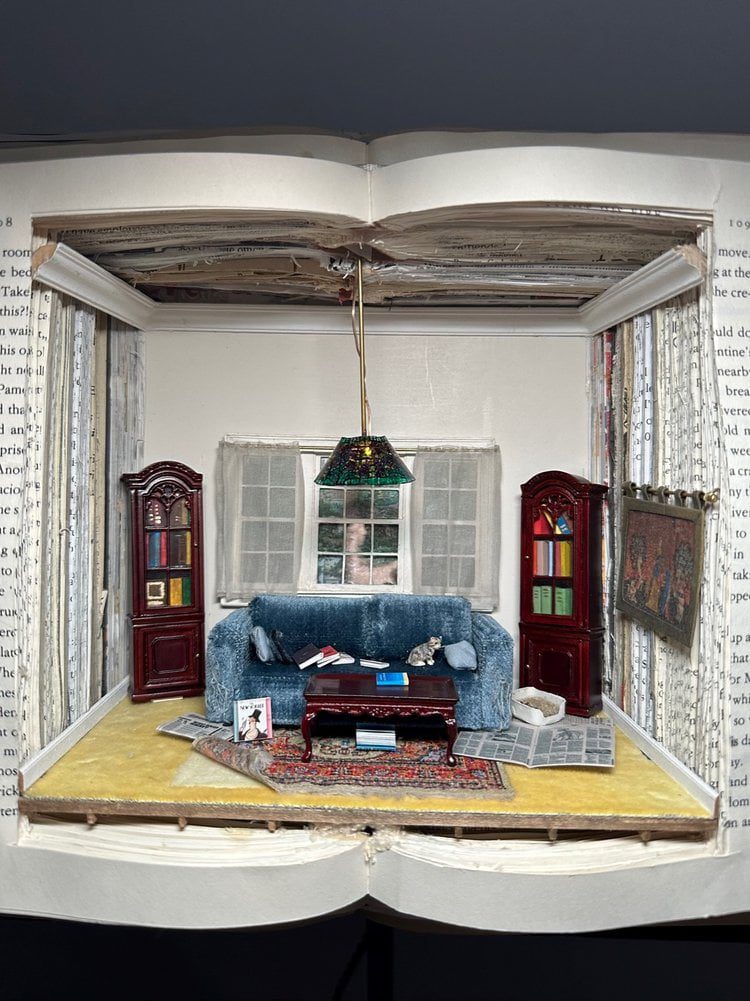

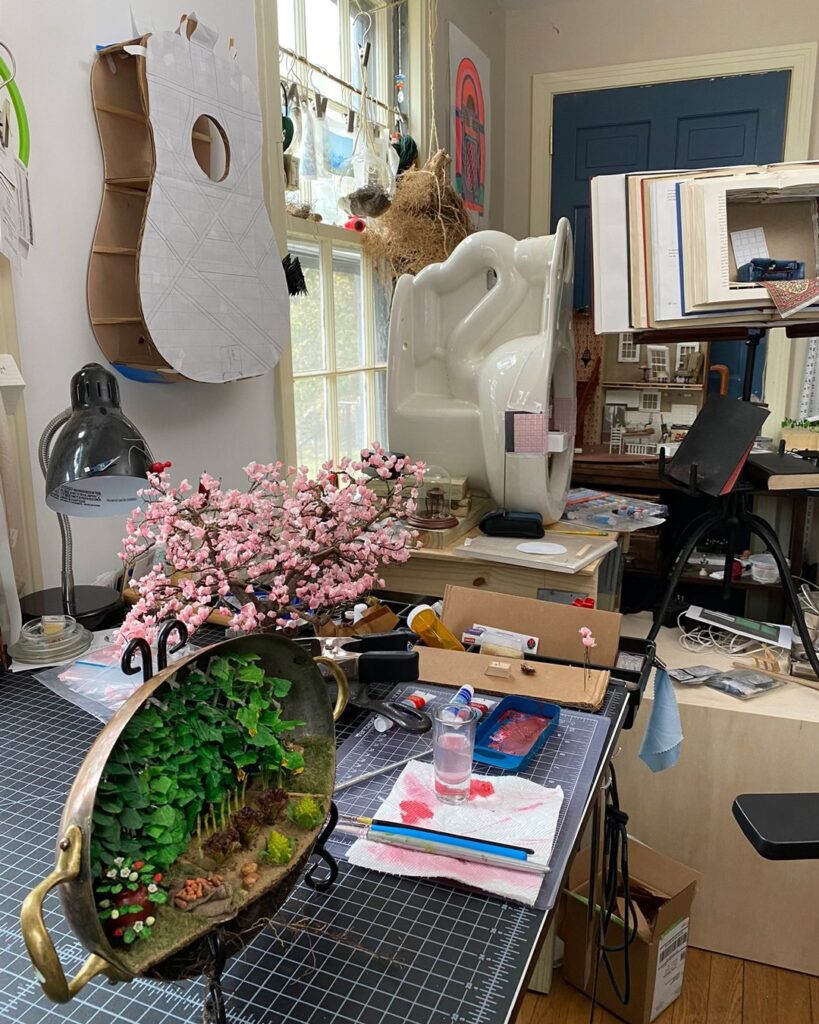

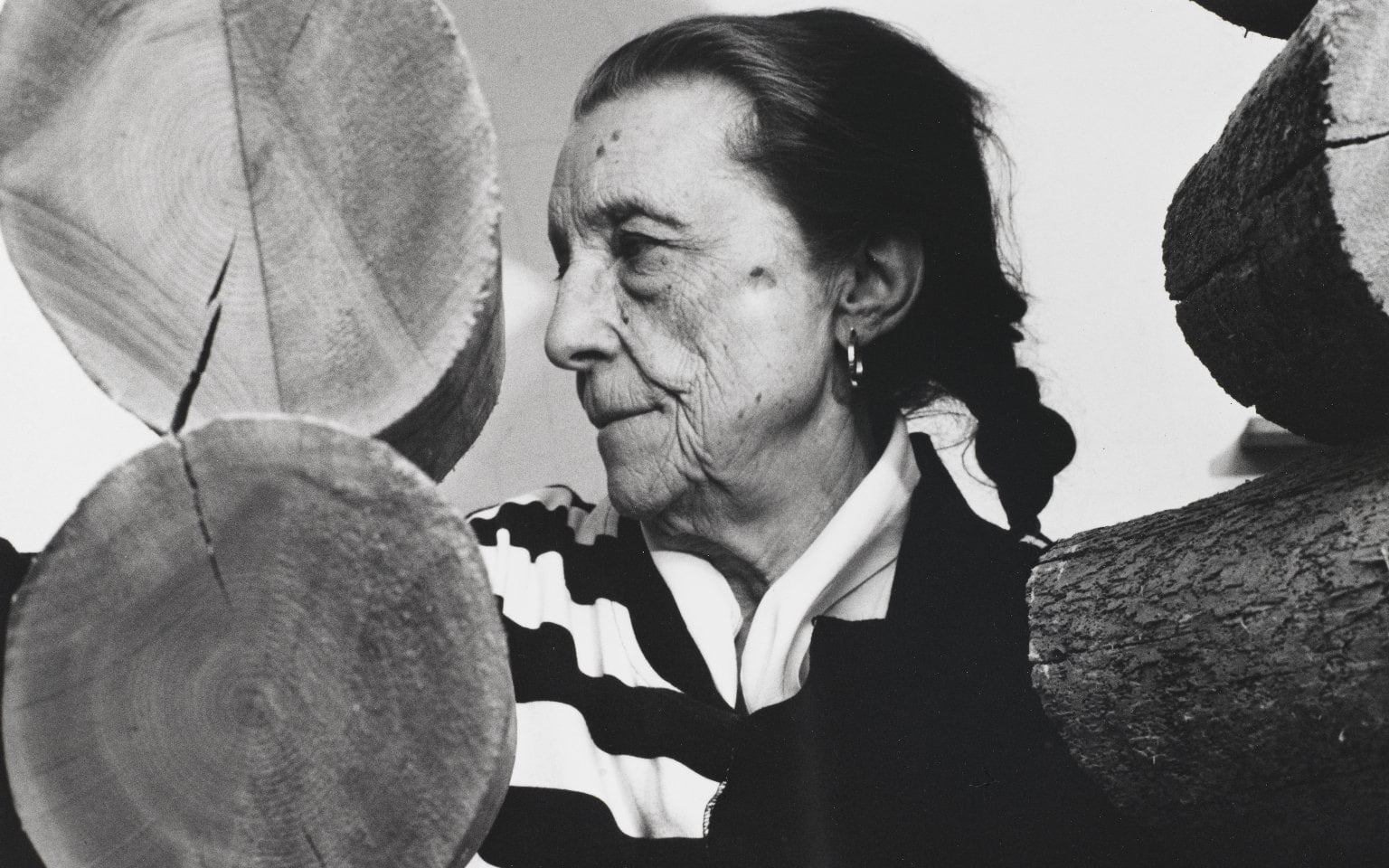

Joanne Steinhardt’s work embraces themes of returning and rebirth, connection, and relationships. Object attachment, the experience a person has when they feel an emotional attachment to an inanimate object, is at the core of Steinhardt’s projects. Psychologically, we imbue possessions with deep meaning (or even human qualities) to fill a void. She collects objects that were the point of attachment for another, repairs, repurposed, and sometimes literally furnishes them. The arduous combination of collection, creation, research, and production, means each piece takes months if not years to create.

A top hat that once belonged to Steinhardt’s maternal grandfather is now home to his painting studio, including a miniature painting that matches the original installed beside the sculpture. Tattered fabrics that have outlived their purpose are transformed into a stiff paper-like substrate for drawings.

Through the making process, Steinhardt is acutely aware of the effect the obsession with the other direction has on herself, and-in-so, considers the outcome of object attachment in a greater societal context. The objects transcend the original people they belonged to and become shared experiences connecting the viewer to their own object attachment and in turn, open deeper societal and cultural discussions.

She collects objects that were the point of attachment for another, repairs, repurposes, and sometimes, literally, furnishes them.

Steinhardt lives and works in the Greater New York City Metro Area. She holds a Master of Fine Arts from the Maine College of Art and a Bachelor of Science in Photography from the RIT School of Photographic Arts and Sciences. Steinhardt’s work has been exhibited at Boissy-le-Châtel, France, The Equity Gallery, Carter Burden, and El Barrio ArtSpace in New York City, and The Tampa Museum of Art, Polk County Museum, and Covivant Gallery in Florida. Joanne has lectured and led workshops at numerous institutions around the US and abroad, including NYU Tisch ITP, the Harrison School for the Arts, and La Biennale del fin del Mundo in Ushuaia, Argentina.

In this exclusive interview with the artist Joanne Steinhardt, she shares how she first started refurnishing memories and how much thought she puts into each project. Joanne also discusses the emotional impact she has whenever she is working on a project and sharing bits about her recent collections and upcoming projects.

1. Joanne, could you tell us how you first became interested in miniaturism and object refurnishing?

I had completed a seven-year-long project that examined the interpersonal dynamic that happens at the tables where people share (or not) meals. The Cookbook Project launched in the summer of 2018 to quite a bit of interest and success. In late 2018 the project was stolen in its entirety; none of the twelve handmade books were ever recovered. The first of the miniature series was a scale recreation of the twelve stolen books. I placed them in the original environment that inspired the lost project – the kitchen and front hallway of the house where I grew up. I scaled the entire environment to fit inside one of my parents’ 1950s valises creating a maquette of sorts of freezing the memory in time. To me, this process helped me not only mourn the loss but create a place I could keep at least the memory of the books close and safe. This first piece is still unfinished and in my studio and is the inspiration for the rest of the series.

The physical is transferred, and the arduous combination of collection, creation, research, and production, means each piece takes months and years to create. Like ancestral altars, these objects become familiar sites of displacement and refuge.

2. What is your approach to the ideation process and determining the best fit for an object?

The inspiration starts with the person who owned the object. Their personality, the nature of obsession with it, and my relationship with the person. The idea, sketching, and research of a larger connection starts with the object. I tend to move them into my work space where sometimes they live for years before I find what to do with them. For example, building my grandfather’s painting studio inside his custom-made top hat shows the split between who he wished to be and the society that he worked so hard to be accepted by but yet trapped him. He was a 1900 immigrant through Ellis Island at age 15. Alone, speaking only Hungarian and Yiddish, he worked to bring his entire family to the US. Instead of painting, he became an industrialist and inventor. While he used his creative skills to a degree, he never really broke free of the monetary definition of success. He started painting when he was seventy. As a little child, I would sit in his studio and watch him paint. Inside that top hat is an exact replica of the studio where I sat with him.

Each of the pieces has its own story; a shut-in who surrounded themselves with books, a woman who lived with pure envy despite her plenty, a man afraid of his own emotions so he used a guitar as a surrogate for personal connections, or a woman stricken with Parkinson’s forced to give up the shoes and clothes that helped define her. In each scenario, the object either serves as a representation or a physical manifestation of the environment that the owner established to grapple with their challenges. I have a personal connection with each individual, and their fixations, denials, and obsessions, have had a profound impact on me, altering and shaping me. The project has helped me to see the not-so-solitary nature of personal struggle and that there exist multitudes of shared experiences. In examining this relationship of the object obsession of “the other” and its effect on me I have come to more clearly consider societal dogma and the impact on broader marginalized groups.

3. Joanne I am curious to know how do you feel emotionally when you refurbish an old memory?

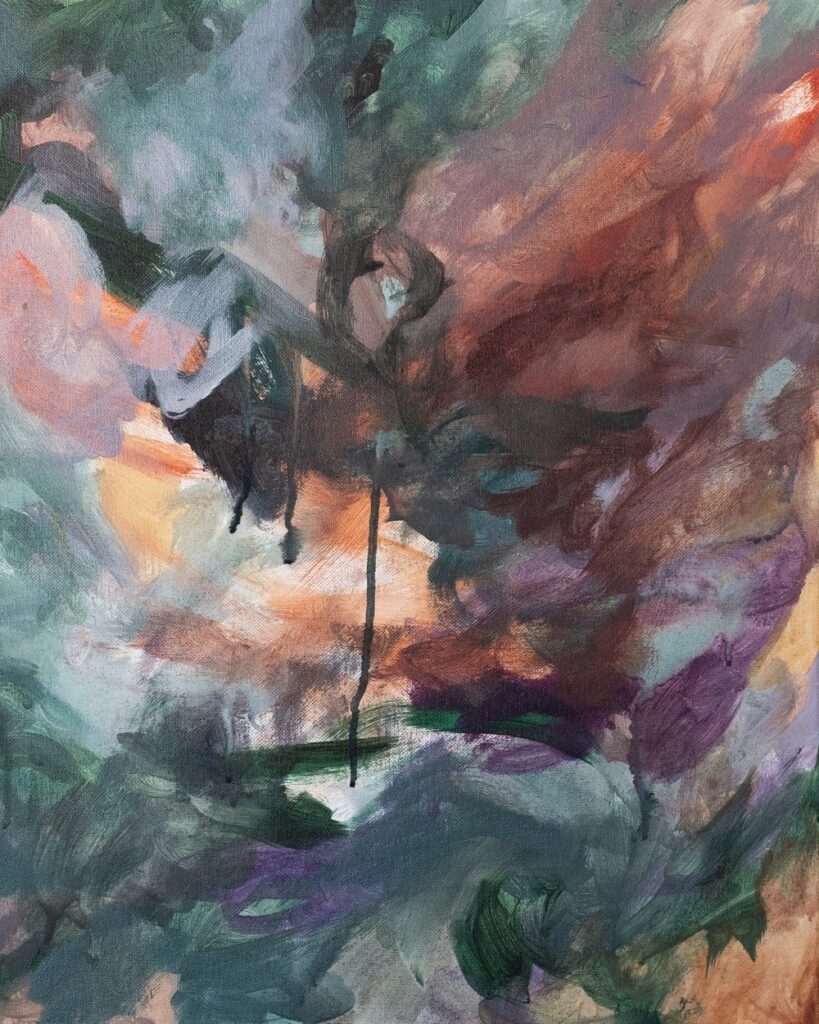

I suppose it is my own form of therapy. My past work addressed many of the same ideas and issues but in a more remote, distanced fashion. This work encompasses a greater part of my identity, therefore, requiring a new, intensified vulnerability that often proves extremely hard for me. Sometimes it is painful or sad, but other times there is intense joy and connection with the person who co-occupies the space of the object with me. I consider myself in constant discussion with my objects; they tell me stories as I work through them, and in those memories, lore, and secrets I create an opportunity for larger discussion and understanding. The technical and emotional demands of this work can be taxing, which is why I work on another body simultaneously. The other project is quite different in form and scale, yet similar in sentiment, allowing my mind to redirect and open to further and intensified discussions with the work.

Object attachment, the experience a person has when they feel an emotional fettering to an inanimate object, is at the core of Steinhardt’s projects.

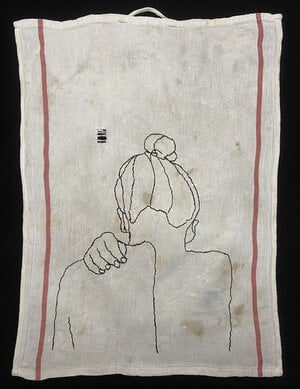

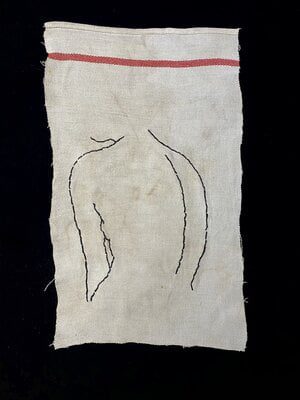

4. The ‘Drawing with Thread’ collection is very refreshing and intriguing. How did you come up with the idea?

Initially, when I was going through the objects I collected throughout the years, I came across a huge bin of old rags. They came from various sources that spanned decades. I was taken with the idea that these sheets, pillowcases, bedspreads, dish towels, etcetera, were considered by someone to have outlived their usefulness, and yet saved them. I was struck by an immediate correlation with what we (as a society and a species) consider useful, in particular women as they age out of their biological intention. I considered ways to combine imagery with the tattered fabric that would re-fortify them; re-purpose them into a new use; one stronger than before. Thus, the thread and the hundreds of stitches not only enhance but also strengthen each piece. As the body matured, just as with the miniatures, the conversation broadened, and giving them new use was not enough. I wanted to give them power. That is when I scaled them up so that they are unavoidable to the viewer. We waste more than enough things as a society, to me, it is due time we not only stop creating so much waste but very pointedly stop discarding people who are deemed no longer of use.

5. Joanne, any recent project you are working on? Please share some details.

The two bodies of work keep me pretty busy, and both are still in process. I am excited to be showing the newest work, the large remnants, during the summer of 2023 in France, and hope to bring them to the US in the fall. As of now, I am working to finalize two solo shows for 2024, as well as several master classes/workshops on topics including, how to give and receive critique, how to mature and focus a creative idea, and the nitty-gritty of the art markets.

Read more about Joanne Steinhardt

Comments 21